The ancient siege ramp at Tel Lachish in the Judean lowlands is the only remaining example of Assyrian military prowess, which during the 8th century BCE, helped bolster the first large-scale empire that controlled wide parts of the ancient Near East, from Iran to Egypt.

Archeologists have known for decades of the presence of the siege ramp, first officially identified by legendary Israeli archeologist (and the IDF’s second Chief of Staff) Yigael Yadin in the late 1970s. It is still clearly visible – albeit that subsequent archeological excavations have shown it was no longer in exactly the same form it took more than 2,500 years ago, as the Assyrian military machine prepared for Lachish’s destruction.

A team of archeologists has reconstructed how the Assyrian army may have built the ramp and used it to conquer the city of Lachish. The team, led by Professor Yosef Garfinkel and Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU), and Professors Jon W. Carroll and Michael Pytlik of Oakland University, USA, drew on the rich number of sources about this historical event to provide this complete picture.

In 701 BCE, Assyrian King Sennacherib laid siege to the flourishing Canaanite city – the second-most important city in the Kingdom of Judah after Jerusalem – as his army attempted to sweep through the entire country and lay waste to it.

The Assyrian assault on the kingdoms of Israel and Judah and the battle for Lachish is mentioned in a number of books in the Bible (2 Kings 18:9–19:37; 2 Chronicles 32; Isaiah 36–37). Assyrian siege ramps are mentioned twice (2 Kings 19:32; Isaiah 37:33), although they do not pay attention to any technical aspects of the war.

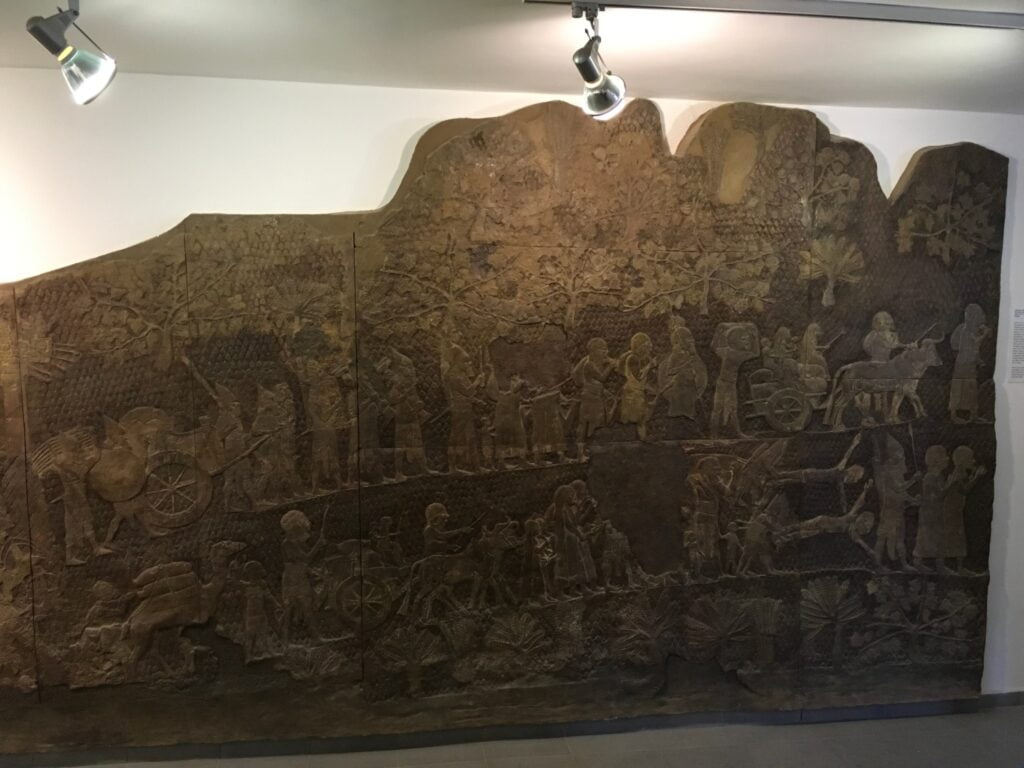

Assyrian reliefs, which French archeologist Paul-Emile Botta discovered in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) at Khorsabad, showed the Assyrian army in various battles.

Akkadian inscriptions, including chronicles and sometimes letters, describe various Assyrian activities in Judah and excavations at various sites in the Near East have uncovered cities destroyed by the Assyrian army. However, the only siege ramp ever to be identified was at Lachish.

Ramp construction

While archeologists could see the remnants of the ramp with their own eyes, what has provided more of a mystery is how the ramp actually got constructed. The surrounding area is not heavily wooded, meaning that the supply of trees was limited. The use of just soil also seemed somewhat unlikely for several reasons, including the slowness of the work necessitated by needing baskets or carts to transfer the soil. They would have had to be made from branches or straw and they would have worn out quickly. In addition, pushing carts over the rough surface of the ramp would have similarly worn out the wheels in little time. The Assyrians also used siege machines – and these heavy pieces of machinery would have quickly sunk into the soil.

The most likely solution, therefore, was the construction of a siege ramp comprised of hundreds of thousands – and as Garfinkel posits, as many as 3 million – stones, made from the local nari limestone that dominates this part of the country – a softish chalk that can be quite easily cut and is good for building.

The assumption was that the Assyrians collected the stones from the surrounding area, although it seems that this was one of the points on which archeologists were less certain. To do so would require long supply chains, which would necessitate protection from attack, while also providing enough food and water for the laborers. Both the biblical account and the images presented on the Assyrian reliefs allude to the use of large L-shaped shields to protect those constructing the siege ramp. They are tantalizing clues that help to unravel a two-millennia-old story and the juxtaposition between the political aspects of the Assyrian reliefs, which concentrate on the booty taken and the Judeans killed in the siege versus the prophet Isaiah’s mentioning of the Assyrian army as an eyewitness to the events.

The solution to that problem of how to find enough material to construct the ramp, was to quarry stones 24 hours a day, with teams of laborers working in shifts. The stones were moved using human chains – and depending on the width of the part of the ramp being constructed, two, three, or more chains could work simultaneously. Archeologists worked out that three human chains – even if they were not working at maximum efficiency could theoretically move some 100,000 stones per day – and up to 160,000 if they were.

“Time was the main concern of the Assyrian army. Hundreds of laborers worked day and night carrying stones, possibly in two shifts of 12 hours each. The manpower was probably supplied by prisoners of war and forced labor of the local population. The laborers were protected by massive shields placed at the northern end of the ramp. These shields were advanced towards the city by a few meters each day,” described Garfinkel.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

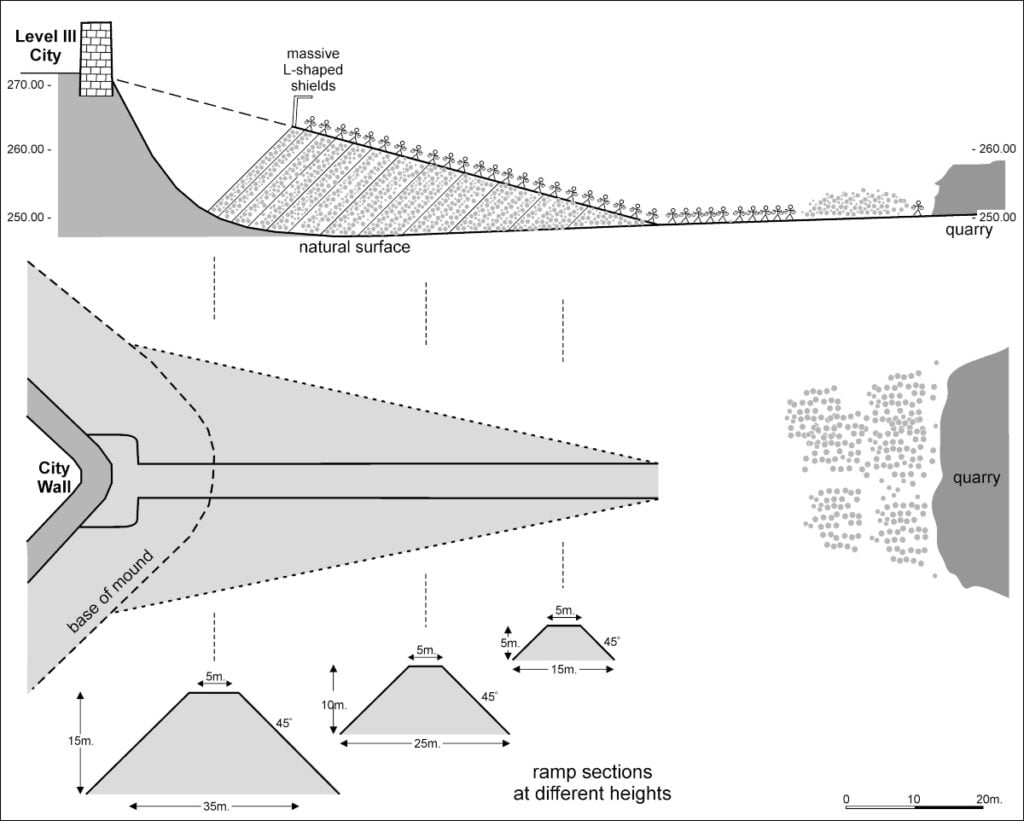

SubscribeThe resulting ramp has a diagonal profile which rises as it gets closer to the city and that actually begins some distance away to protect the laborers from attack from above. At the beginning, the ramp is quite low and hence the segment constructed each day is longer. As the ramp becomes higher, a shorter segment is constructed each day.

The length of the ramp is dictated by two factors: the height of the mound above the local surroundings and the angle of the ramp. This angle is in turn dictated by the weight of the siege engine that is to be pushed up to the city wall. Lighter engines can be pushed up a steeper and shorter slope, while heavier engines will need a more moderate slope and consequently a longer ramp.

The ramp is basically a road bringing the Assyrian army into direct contact with the city wall. Most of the ramp can be a relatively narrow passageway, but adjacent to the city wall a larger space is needed to accommodate several battering rams and additional soldiers.

Once the main body of the ramp was constructed, it was necessary to smooth out and level off the top surface so that heavy siege engines – weighing up to a ton – could be pushed up the ramp until they faced the city walls. The ram, a large, heavy wooden beam with a metal tip, battered the walls by being swung backward and forward. Garfinkel suggests that the ram was suspended within the siege engine on metal chains, as ropes would quickly wear out. Indeed, an iron chain was found on the top of the ramp at Lachish.

Previous archeologists suggested that a mixture of stones and plaster was used to finish the ramp, although the use of the latter was considered unlikely due to the necessity of using large amounts of wood to keep the kiln fires burning in order to manufacture it. Garfinkel’s conclusion was that just enough earth was dumped on the stones to stabilize the top, with large wooden planks to produce an even enough surface on the ramp to allow the siege engines to pass over them.

It is possible to extrapolate from both the sources and the physical evidence which remains, that the Assyrian army must have possessed a number of artisans – particularly skilled in the complex carpentry work of constructing siege engines. It is also likely that prisoners of war and slave laborers provided carpenters for the simpler tasks.

Drone imagery provides answers

In order for today’s archeologists to better understand the topography, the precise shape of the ramp and what likely remained after more than two millennia, the amount of stones needed and the location of the quarries supplying the stones, a SenseFly Ebee small Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) – a fixed-wing drone – was deployed. It flew linear transects and gather overlapping georeferenced imagery averaging 2.5 cm in pixel resolution.

The aerial survey that the archeologists carried out, allowed them to not only review the hypotheses of those who had previously assessed the site but also to reach their own conclusions. One of the things they found is that the stones were not organized in a specific pattern but were rather dumped randomly. The haste of the ensuing battle meant that there was no time to be absolutely exact, highlighting how some parts of the ramp were built as steeply as a 45-degree angle.

To get further confirmation, Garfinkel explained that he is “planning excavations in Lachish, at the far edge of the ramp in the quarry area – this might give additional evidence of Assyrian army activity and how the ramp was constructed.”

Related posts

Rehabilitation Nation: Israeli Innovation On Road To Healing

Israeli High-Tech Sector 'Still Good' Despite Year Of War

Facebook comments