Over the past decade, Israeli cuisine has become all the rage as Israeli chefs found celebrity with reimagined local foods and dishes brought to the Holy Land by Jews from the Diaspora.

At the same time, a tiny religious sect in Israel has kept its own culinary traditions alive for some 3,000 years, far from the limelight of cooking shows, cooking competitions, book releases, and award-winning restaurants in world capitals.

SEE ALSO: Chef Michael Solomonov Launches New Web Series For A Taste of Israel

This may soon change with the release of a new cookbook that looks at the foods and cooking traditions of the Samaritan community, an ethnoreligious group that traces its roots to the ancient Israelites and regards itself as the most loyal adherents of the Torah as transmitted to Moses by G-d. They are keepers of what they say are the oldest, hand-written Torah manuscripts in the world, penned in the Samaritan alphabet and considered scripture.

The “Samaritan Cookbook” is a unique journey into the kitchens and the history of this ancient sect, who according to belief, are descendants of the tribes of Ephraim, Menashe, and Levi. Their two biggest holidays are Sukkot and Pessah, both Torah festivals, when the Samaritans host hundreds of guests – Israelis, Palestinians, tourists – for elaborate, colorful ceremonies involving food and drink.

These events often make international headlines accompanied by striking photos of Samaritans dressed in traditional garb against the backdrop of Mount Gerizim – the holiest site according to Samaritan belief. The small community, fewer than 1,000 today (it numbered over a million centuries ago), is split between the southern Tel Aviv suburb of Holon and the town of Kiryat Luza, just outside the West Bank city of Nablus on the slopes of Mount Gerizim. Samaritans speak both Hebrew and Arabic and navigate a complex identity influenced by Jewish Israelis and Muslim Palestinians.

Rooted in Samaria, their cuisine is Levantine – similar to that eaten by Israelis, Palestinians, Lebanese and other communities in the Levant – and relies on fresh, natural ingredients. The book features dozens of recipes that combine freshly-grown fruits and vegetables, meats from farm animals (chicken, turkey, sheep) and strong, flavorful spices used in Samaritan cuisine, with a rich farm-to-table (and butcher-to-table) tradition.

Dishes include a cauliflower with rice maqlouba, lamb meatballs with pine nuts, chicken with za’atar, a guacamole-like dip with a Middle Eastern twist, Samaritan knafeh, and a delicious-sounding sesame and anise cake. Arak and anise tea are the prevailing beverages.

“The book covers an ancient Israelite dimension: on the one hand, very traditional with a foot in history and in the past, but at the same time very modern and Levantine,” says Ben Piven, one of the editors of “Samaritan Cookbook” and a journalist who previously spent over a decade immersed in the societies and languages of the Middle East.

Piven worked with Avishay Zelmanovich, a scholar of Middle Eastern cultures and Jewish history, and Benyamin “Benny” Tsedaka, a Samaritan academic, author, lecturer, unconventional historian, and informal “secretary of state” for the community, as Piven describes him, to put together and publish “Samaritan Cookbook.”

The work was inspired by a 2011 Hebrew-language cookbook released by Tsedaka with 284 recipes gathered by dozens of Samaritan women, including Tsedaka’s mother and aunts. For “Samaritan Cookbook,” Piven tells NoCamels that the trio selected a few dozen recipes they felt would be most compelling for an international audience.

“We wanted to make this book accessible, with charming, simple recipes,” and ingredients and flavors that people could find easily, Piven explains.

The book is written in English, with recipe titles in English, Hebrew, and Arabic. It is divided into chapters – starters, mains, desserts, with special sections on Sukkot and Pessah and one on the Samaritan pantry, with must-haves such as anise, cumin, za’atar, paprika, and turmeric.

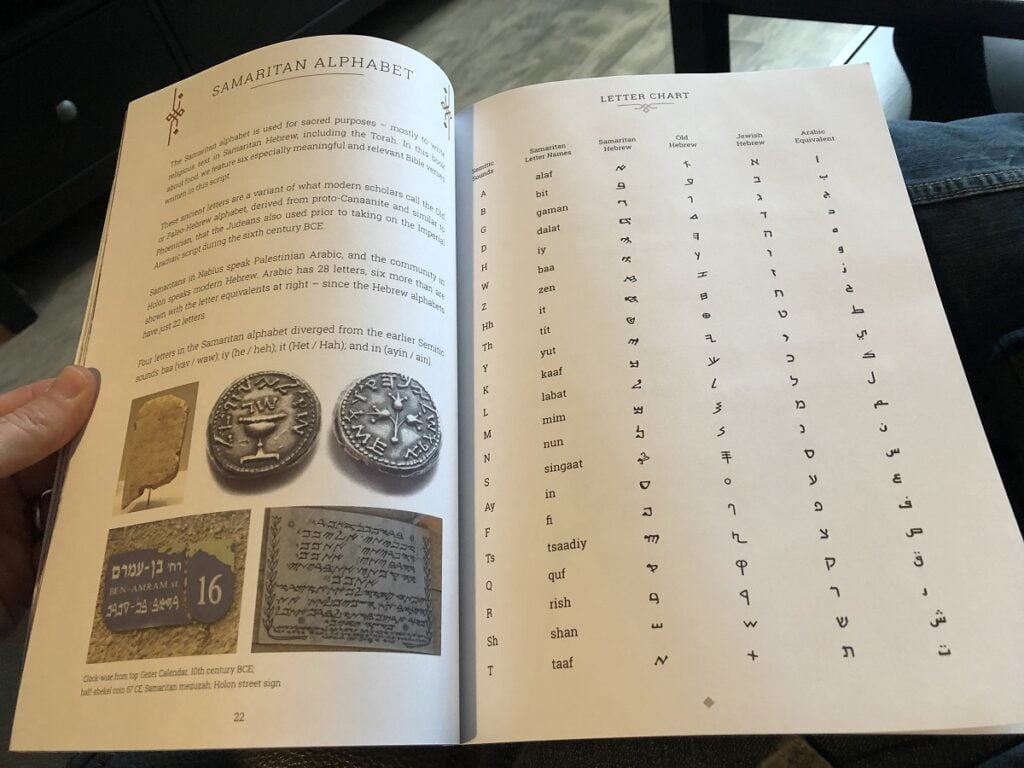

The Samaritan alphabet makes a special appearance in the cookbook, which also incorporates verses from the Samaritan Torah such as “By evening, you shall eat meat, and in the morning, you shall have your fill of bread. And you will know that I am the Lord, your God,” Exodus 16:12 (Samaritan version), and “A land of wheat, and barley, and grapevines, and fig trees, and pomegranates; a land of olive oil and honey,” Deuteronomy 8:8 (Samaritan version). These are the Seven Species for Samaritans, according to scripture.

The genesis of ‘Samaritan Cookbook’

Piven and Zelmanovich first met in Israel nearly 15 years ago. Around the same time in 2007, they connected with Tsedaka while working on a story on the Samaritan community, a popular topic with journalists in the region.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeTheir interest and passion for Mideast cultures led them to create One Semitistan, a cultural organization that examined the region’s linguistic heritage and the links between Semitic languages such as Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Amharic.

Meanwhile, they developed a rapport with Tsedaka and stayed in touch over the years. Piven had in the meantime moved to New York, and he and Zelmanovich met up with him in the city when he would be on his annual US lecture series.

In such a meeting in 2015, an initial plan for an English-language book on Samaritan cuisine started to formulate, Piven tells NoCamels, and the trio quickly got to work. The idea was to go beyond food and into the history and unique context of these ancient Israelites to explore who they are and how they survived all these years.

“Everyone loves good food. And food is often an entry into a community. We were interested in using the Samaritan model as an example of a cross-cultural bridge between Israelis and Palestinians, between Hebrew and Arabic, as a model for co-existence,” Piven says.

“We see beyond it being about food. There really is something about peace-building where if you can appreciate the same traditions, influences, and music, and languages, and heritage, you realize how much these narratives are intertwined,” he tells NoCamels.

“Samaritan Cookbook” lives in this concept of peace-building. The Samaritans have a divided identity where some live and work in Israel, and serve in the Israeli army, while others live in the West Bank among Palestinians with whom they share similarities. They straddle both worlds, Piven explains.

“It’s a window to understanding the [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict, and a possible living solution where the land belongs to everyone,” he tells NoCamels.

The Samaritans “stayed on the land, unlike the Judeans who became a Diaspora people [due to conquest and persecution.] They are very tied to the land because they never left,” he says. “This was not the norm for either Israelis or Palestinians.”

This attachment is reflected in the cuisine and the traditions. Piven tells NoCamels that over the years, Samaritan cuisine has come to represent a sort of “median Levantine cuisine, a mix of all these places.”

Piven believes the “Samaritan Cookbook” will resonate with five main groups: coexistence supporters interested in bringing Middle Eastern communities together, scholars studying this one-of-a-kind ethnolinguistic sect, Christian communities interested in biblical heritage and looking to know more about “what Moses ate, or what Jesus ate” from the ancient Israelites, Jewish people fascinated by a distinct Israelite heritage, and foodies interested in the Mediterranean diet and its health benefits.

In the future, Piven, Zelmanovich, and Tsedaka hope to publish versions in other languages to reach more audiences.

“Samaritan Cookbook” is available for purchase through the publisher, Wipf & Stock, and on Amazon.

Related posts

Rehabilitation Nation: Israeli Innovation On Road To Healing

Israeli High-Tech Sector 'Still Good' Despite Year Of War

Facebook comments