In today’s global political climate, which has been called a tumultuous time, the role of the political cartoonist has become muddled. At its very core, a political cartoonist is someone whose work plays a crucial role in the political discourse of a free society.

Ann Telnaes, president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and a cartoonist for the Washington Post, has said that the “job of an editorial cartoonist is to expose the hypocrisies and abuses of power by the politicians and powerful institutions in society.”

SEE ALSO: Israeli Designer Creates Hilarious Solutions For Everyday Local Problems

“I think our role has become even more urgent with the new political reality in 2017,” she added in reference to the year Donald Trump began his term as president.

But is this art a form of activism that ultimately seeks political or social change? Steve Lambert, a veteran activist, and Stephen Duncombe, an accomplished artist of The Center For Artistic Activism suggest that art does not have such a clear goal.

Avi Katz, an Israel-based US-born illustrator and cartoonist, whose career spans more than 30 years, would likely agree.

Katz, who resides just outside Tel Aviv, was a staff artist of the bi-weekly magazine The Jerusalem Report when he was let go in July 2018 following the publication of a political cartoon that depicted Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and an entourage of coalition members as pigs. The drawing, based on a real, award-winning photo taken by Haaretz photojournalist Olivier Fitoussi, was an homage to George Orwell’s Animal Farm and included a quote from the famous 1945 novel at the top of it.

Katz drew the cartoon as a commentary on the passage of the controversial nation-state law, backed by Netanyahu. The law specifies that Israel would be defined as the nation-state of the Jewish people and while all citizens have human rights, the right to self-determination in the country would be “unique to the Jewish people.”

Katz, who illustrates children’s books and works as a freelance cartoonist, tells NoCamels there was no form of activism behind his cartoon.

In an editorial, The Jerusalem Post, which owns The Jerusalem Post newspaper and The Jerusalem Report magazine, called the cartoon “reminiscent of anti-Semitic memes used against Jews throughout history,” completely disregarding the reference to the famous novel and its critique of tyranny.

For Katz, it was freedom of expression based on a photograph of Likud politicians posing for a congratulatory selfie amid controversy and sharp opposition mainly from Israel’s Arab and Druze communities.

“Wanting people to think is a better summation of what I’m after,” he tells NoCamels of his artwork. “I was just trying to talk about what was happening in a situation.”

“I just want to be in a position where when something happens, I can illustrate what I think of it,” Katz adds.

That is exactly what famous Haaretz political cartoonist and caricaturist Amos Biderman has been doing for decades, with some memorable results. In 2014, Biderman drew Netanyahu as a pilot flying a plane into a skyscraper, in a scenario reminiscent of the September 11 attacks. The cartoon was meant to be a critique of Netanyahu’s handling of Israel-US ties under the Obama administration at the time, and it launched a global storm of controversy.

Despite the upheaval, Biderman said the criticism was fair.

Haaretz Daily Cartoon – 30/10/14 http://t.co/ueOAVVKkc3 pic.twitter.com/xWXJ5OgQL6

— Haaretz.com (@haaretzcom) October 30, 2014

“I was mocking Bibi,” he said at the time in his defense, using Netanyahu’s nickname. “He’s been acting like a bull in a china shop with the United States, which is Israel’s most important strategic asset.”

Biderman also said he has never censored his cartoons, which have addressed many controversial issues.

“I have drawn cartoons depicting every war that Israel has fought, including the Yom Kippur War – which I was involved in – where we suffered thousands of casualties. I have used some of Israel’s greatest tragedies as the background for my cartoon… I never imagined that by using an image that evoked 9/11 I would cause such a storm.”

The problem, according to Katz, is that cartoonists are often pushed into a position where they have to defend their right to evaluate or even critique a political situation.

As an example, he brings up the controversial cartoon published in the global edition of the New York Times in April this year where Netanyahu is depicted as a dachshund wearing a Star of David collar and leading a blind, yarmulke-clad US President Donald Trump. The cartoon, created by a Portuguese cartoonist, António Moreira Antunes who works under the mononym Antonio, was widely criticized and labeled blatantly anti-Semitic. The New York Times apologized and announced that it would cease publishing political cartoons.

Pence condemns New York Times over Netanyahu-Trump cartoon https://t.co/IN1AC2THRG

— The Times of Israel (@TimesofIsrael) April 28, 2019

The drawing “was not very smart,” Katz says, adding that it may have even been ignorant. But he doesn’t believe it was intended to be anti-Semitic as other organizations and individuals, including the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee and Trump himself, have claimed.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeAs for Antunes, he was largely unapologetic, and told The Jerusalem Post that he did not “seek controversy” and only sought to “critique Israeli policy.'”

Michel Kichka, one of Israel’s leading political cartoonists and comic book artists, as well as a former president of the Association of Israeli Cartoonists and a senior lecturer at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, also reacted strongly to the debate over the political cartoon.

“It was a cowardly decision,” he says of the Times’ decision to stop printing political cartoons. “A newspaper has to defend a cartoon they have chosen to publish.”

Kichka, who spent a number of years doing influential work for Cartooning For Peace, a movement of the United Nations Regional Information Center representing 203 editorial cartoonists from 67 different countries who draw to better understand and respect different cultures and beliefs, does believe that some cartoonists are artistic activists in their own way.

“I doubt deeply that the cartoon is able to make a better world, but I think it is there to try,” he tells NoCamels in a detailed phone interview.

The real activism, he says, is just making the viewer react to the drawing.

“I like my readers and followers to stop for a few seconds, to watch, to agree or disagree, to react,” he explains, “We have been given a small space of freedom. In this space, we can be provocative.”

This summer, Kichka was honored for his work and awarded the prestigious Francine and Antoine Bernheim Lifetime Achievement Award by the French Judaism Foundation.

Cartoons should make you say, “I disagree with you but I will fight to give you the freedom to express. It is possible to be provocative and tolerant, borderline and respectful,” Kichka says.

While Kichka calls himself a “softer cartoonist,” he is outspoken when it comes to his views on the modern state of Israel and how much it has changed since he moved to the country from Belgium in 1974 to attend a four-year program at Bezalel.

Today, he is a senior lecturer at the institution and tells his students not to be afraid to express their views through their art.

“I want them to feel they have the tools, talent, and the voice to use and I want to help them use it,” he says.

As a professor of visual communications at Bezalel since 1982, Kichka is known for mentoring a generation of award-winning Israeli cartoonists including Asaf Hanuka, an Israeli comic book writer, artist, illustrator and teacher, David Polonsky, the art director and lead artist for animated Israeli documentary “Waltz With Bashir,” and Rutu Modan, an established comic artist in Israel and one of few established female comic artists in the world.

Many of her graphic novels – Modan has published three and is currently working on a fourth – also have strong Israeli female characters.

Besides illustrating for Israel’s leading daily newspapers, she also edited the Hebrew edition of the US satire publication MAD magazine with Yirmi Pinkus. In 1995, she and Pinkus co-founded Actus Tragicus, an internationally acclaimed collective and independent publishing house for artists.

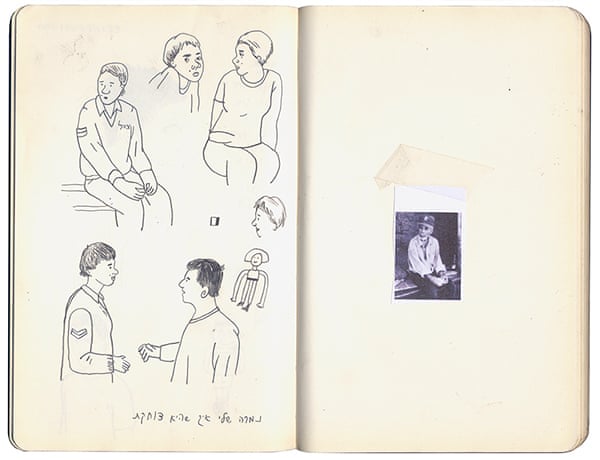

“These are sketches for the lead character of Numi, a young female soldier in Exit Wounds,” Modan told British daily newspaper The Guardian in an intricate look inside her sketchbook. “I wanted her to be charming in the photo. In most comics — and in fact most cultures — the woman is always beautiful. It’s very frustrating for regular women like me. I wanted to show that a man can fall in love with a woman who is awkward and not pretty,” she says.

“Most of the art I consumed was about men. The female was a side character. I had to identify with a side character, even though I grew up with a strong mother and a house run by women,” she explains.

Modan doesn’t look at her commentary on society or Israeli life as artistic activism, though. “Spreading a message is not what I’m trying to do,” she tells NoCamels, “It’s not a message, it’s a point of view.”

Modan says she’s not opposed to activism and her part in it when it comes to changing the world’s perception of strong females and Israeli society. “It’s just someone trying to do something that adds something good in the world,” she says. “My art has something to do with that.”

“I don’t believe it’s a direct change that can influence people to think differently about Israel. I want to show people what I see. When I draw Tel Aviv, I draw it like I see it,” she says. “You have to let the audience decide for themselves. I’m just trying to share a point of view.”

Related posts

Rehabilitation Nation: Israeli Innovation On Road To Healing

Israeli High-Tech Sector 'Still Good' Despite Year Of War

Facebook comments