Imagine being able to understand your pet’s feelings by simply snapping a photo of them.

Right now, AI is learning to do just that, by recognizing the subtle facial cues and muscle contractions of animals that we humans cannot see.

Researchers at the Tech4Animals lab, in Haifa, northern Israel, are training this algorithm by using thousands of photos and videos of cats, dogs, and even wildlife.

It could help vets understand when animals are in pain, and allow pet owners an insight into their animal’s state of mind.

“Unlike humans, animals cannot tell you what they think or what they feel,” says Professor Anna Zamansky, who founded the lab 10 years ago.

“The idea of the lab is to do anything related to AI and technology to promote animal welfare, and to develop tools to study behavior and internal states, such as pain and emotions.”

The lab analyzes information from academic papers and ongoing research and collects images from scholars studying animal behavior worldwide.

It does not conduct studies on animals itself and never benefits from experiments that inflict pain on animals.

”We just want to do what’s good for animals, because there are so many other researchers doing things that are good for people,” says Prof. Zamansky.

“We’ve had cases where researchers came to us with really fascinating data from experiments done on animals in order to develop cures for cancer. But we only engage with data that can promote animal welfare, where no animal is harmed during the preparation of the data.”

Prof. Zamansky believes there are many benefits of developing AI to better understand animals, such as using machines to help vets determine whether an animal is in pain.

But beyond that, she and her team are self-proclaimed hopeless romantics who want to ‘talk’ to animals.

“We believe that AI is finally ready to do it better than humans. So we just want to make a ‘digital Dr. Dolittle’, and understand what the animals are thinking and feeling.”

She shares two studies that Tech4Animals collaborated on to train its AI, and bring us one step closer to bridging the communication gap between humans and animals.

Tiny details on cats’ faces reveal whether they’re in pain

Any cat owner knows that their feline companion is notoriously difficult to read. In fact, in a study of over 6,000 participants, fewer than 60 percent were able to accurately identify the mood of a cat from watching brief videos… and most of them were cat owners.

Cats’ instincts tell them to hide signs of pain or distress, likely an evolutionary trait retained from their wild ancestors. As a result, house cats may suffer from chronic pain without their owners knowing or ever taking them to get treatment.

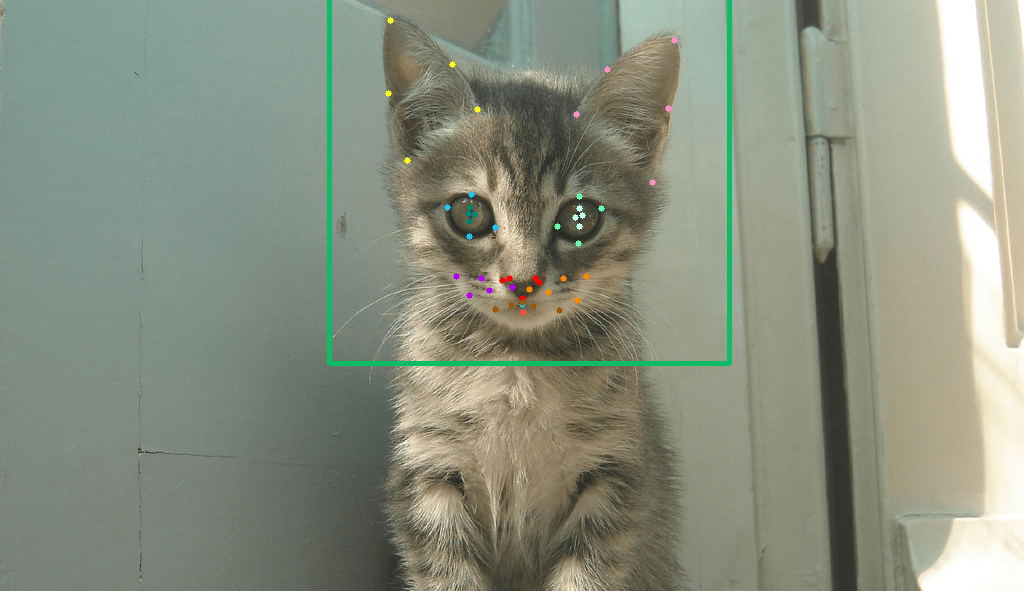

In a recently published study, researchers from the Tech4Animals lab successfully trained their AI to identify when cats are in pain, and achieved an accuracy of 72 percent.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThe research was based on a study of 29 female British shorthair cats, whose faces were photographed before and after sterilization – while they were still under the influence of painkillers, and after they had already worn off.

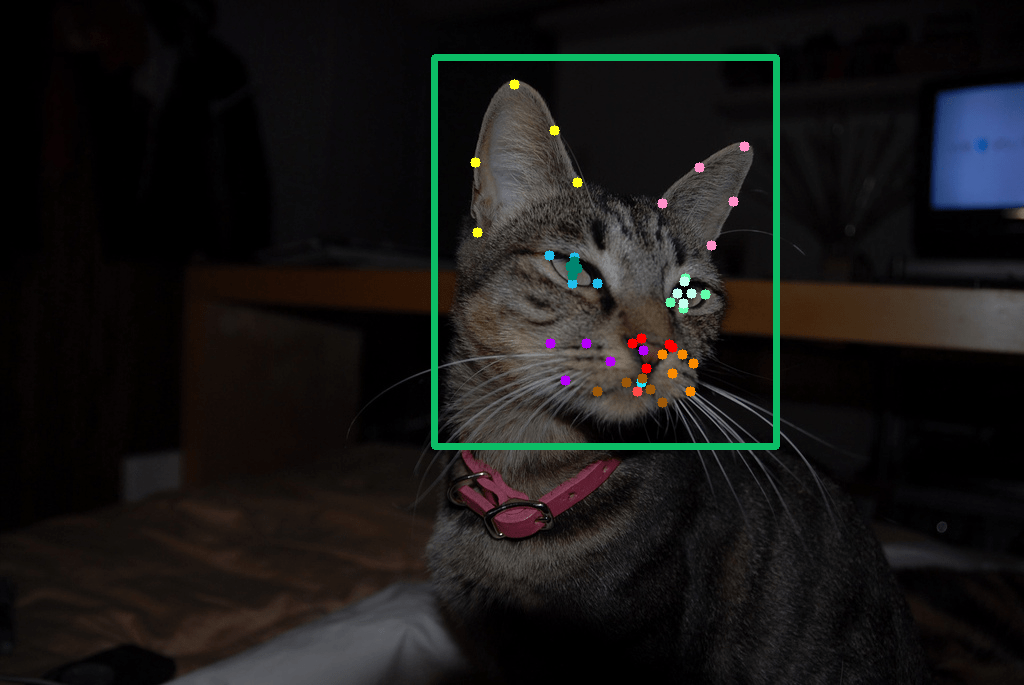

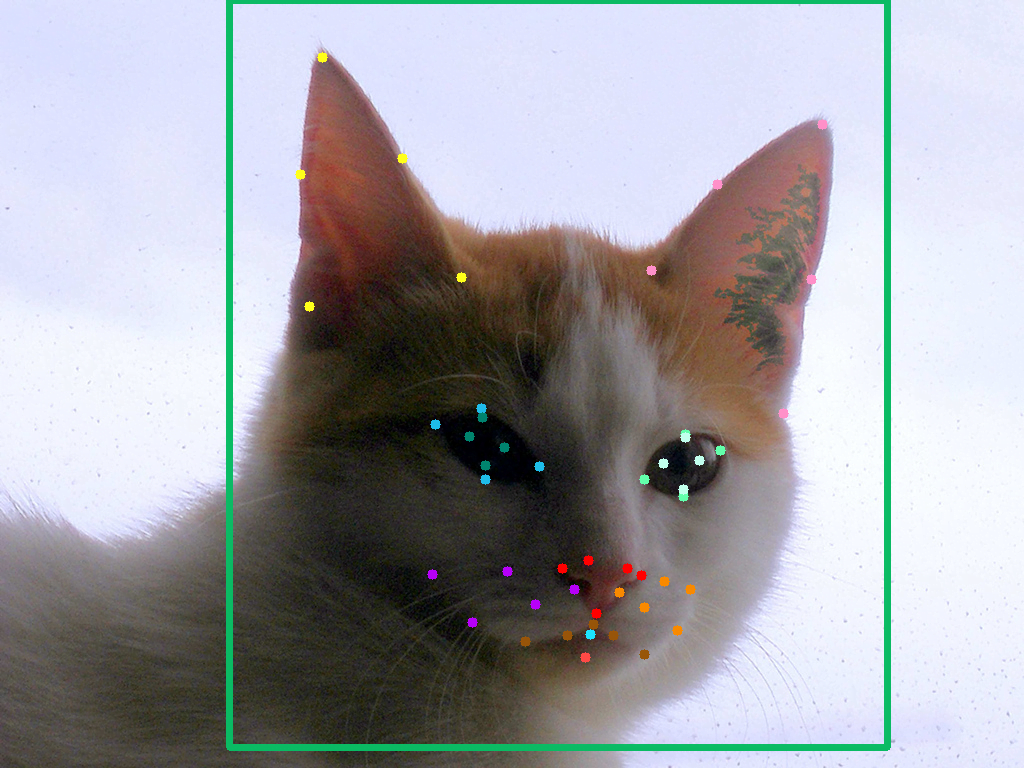

The AI was able to recognize when cats were in pain by analyzing particular points on the face – specifically the slight muscle contractions around the eyes, whiskers, and ears.

“This is actually universal for all species. When we feel pain, our muscles are contracting – but it looks different on each animal,” explains Prof. Zamansky. “With cats, the eyes slightly close, and the ears and whiskers go down.”

Although humans have already understood these pain cues in cats, teaching AI to detect 50 specific points on the face is much more precise, and can help vets and owners identify cats that are in pain whose muscle contractions are even more subtle.

The study was conducted by PhD candidate Marcelo Feighelstein from the Tech4Animals lab, in collaboration with colleagues from the UK, Germany, and Brazil.

Ear movements can tell us what a dog is feeling

Using AI to read animals is still a relatively new field, and the majority of research conducted thus far has been to identify pain.

Researchers from Tech4Animals wanted to train algorithms to understand the emotional states of dogs, just by reading their facial expressions.

They used videos of 29 labrador retrievers, which were trained to expect food and toys after a certain time. They filmed the labradors’ faces when they received the reward that they expected, and when they didn’t and felt frustrated.

The AI identified that certain traits were more common when the dogs were feeling frustrated, which included them licking their nose, flattening their ears, parting their lips, dropping their jaw, and blinking. The most common trait seen in excited labrador retrievers was their ears going up.

“You can normally tell what a dog is feeling by looking at their body language, but if you only have access to facial expressions, it’s more difficult, because these movements are very, very delicate,” says Prof. Zamansky.

“In some breeds, it’s practically impossible to see – like pugs and French bulldogs, whose expressions can only be determined by the way their wrinkles are formed.”

The study was conducted by PhD candidate Marcelo Feighelstein and Tali Boneh-Shitrit from the Tech4Animals lab, in collaboration with Annika Bremhorst from Switzerland.

Ongoing studies: an AI-driven app for zookeepers, and studying pain in pigs

Tech4Animals is also involved in several ongoing studies. One is using AI to analyze the health records of tigers and lions in zoos, and ultimately create an app for zookeepers to help them book medical checkups in advance.

They’re also using video footage from factory farms to study pain in pigs. They are currently castrated without painkillers because until now there has been no way of objectively measuring the species’ pain. Tech4Animals is hoping to change that.

“When I speak about this, some people respond by asking me, ‘what’s the point of preventing pain in pigs if they’re going to be slaughtered anyway?’ I think that it’s our society’s responsibility to at the very least minimize their pain,” says Prof. Zamansky.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments