Forgotten sandal set Dead Sea sculptor on a 20-year journey of discovery

It started by chance. Israeli sculptor Sigalit Landau left her sandal in the Dead Sea, and found it a week later, coated in a layer of salt crystals.

“By then, it was already starting to transform into a Cinderella slipper,” she says.

She was visiting the lowest point on Earth to prepare for an artistic video of her floating naked within a six-meter long spiral raft of 500 watermelons.

That was nearly twenty years ago. Since then, she and her team of assistants have gone on to submerge hundreds of different objects in the Dead Sea, where the water is 10 times saltier than ordinary sea water.

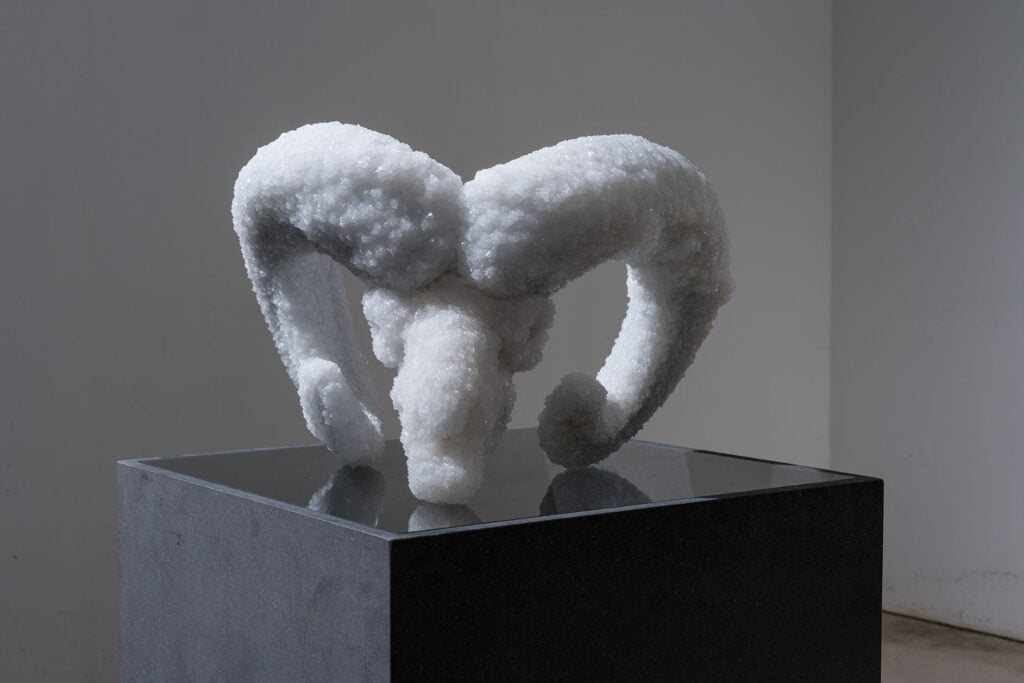

Many of her salt-encrusted sculptures – including barbed-wire, musical instruments, shoes, and dresses – are on display today at the Israel Museum of Jerusalem.

Now she says it might be time to wrap things up, and focus on other projects, like a bronze sculpture she is working on for the new National Library in Jerusalem. “I think I’ve done enough,” says Landau, 53, after two decades when she’s often started her working day at 3am.

The process is very demanding, her team’s working conditions aren’t improving – and they’re just not as young as when they first began.

There’s a story behind each piece. One sculpture, a dress, is an exact replica of the one worn by Hanna Rovina, the Israeli actress known as the First Lady of Hebrew Theatre.

Her most famous role was that of Leah in The Dybbuk, a play about a maiden who is possessed by the spirit of her dead lover, Khanan, who her father rejected as her suitor.

Landau wanted to marry her to the sea, and turn her black dress of mourning to a beautiful, salt-coated wedding dress.

A lot of trial and error was involved when submerging the objects. Some materials don’t maintain their integrity under such a high concentration of salt water – like brass, which will corrode.

“When you make art, you’re in control to some extent,” she tells NoCamels. “But it’s very interesting to work with nature and to not know what the outcome will be.

“Artists and scientists are not so different when it comes to materials and learning. We both just have to experiment.”

Flimsy items like dresses, will lose their ‘waviness’, and will become rigid. So she ties them to frames until their forms are fixed. “We use weights, ties, knots, and frames to keep things underwater.”

For some pieces, she applies resin or a little wire beforehand. “But I try not to do too much – I let the sea do what it wants, and I like to be surprised.”

She then treats them with a lacquer to keep the “crying” to a minimum – that’s when humid air melts some of the solidified salt water.

“Two months into my current show, there’s much less mopping,” she jokes. “But we still announced the possibility of the works crying in the first few weeks while we were in the early stages of planning the exhibition for the Israel Museum.”

Landau and her team usually create the art pieces during the summer months. They leave their Tel Aviv studio at around 3 am, stock up on regular water (because there’s no place to shower at the Dead Sea) and other necessary gear, and get there at around 6 am.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

“In the summer, the water is like soup, even in the early hours of the morning when it isn’t hot yet. But that’s what you need to create crystals.

“If you come two months earlier, the water will definitely be more refreshing to work in, but we can’t get that same magic without high temperatures.”

In cooler temperatures, the crystallization is more powdery. “In summer, we call the crystals shesh besh (backgammon dice).”

She and her team check on the pieces three times a week, until Landau is satisfied with the way the salt has clung to them.

There isn’t an exact science to coating sculptures with crystallized salt, and after years of doing this, some things still catch her by surprise.

“At one point, I lifted a crystallized object from the water that was so heavy that I couldn’t even remember what it originally was,” says Landau.

But from that, she was inspired to create a sculpture that would dissolve on a frozen lake to see what would happen. It only succeeded on the third attempt, when they understood that the salt would stop dissolving at temperatures lower than -17 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit). It rarely gets colder than 16 degrees Celsius (60 degrees Fahrenheit) at the Dead Sea.

Landau says that half of all the objects she submerges don’t become art works to her liking, for various reasons. And some objects, like the skeleton of a dove which she purchased from a laboratory, just don’t fit her vision once they emerge from the water.

Big items take a few months to crystallize nicely. Small objects take a few weeks, especially in the summer. Any longer and they become so encrusted that they’re unrecognizable.

Landau has several objects she enjoyed submerging the most. Shadow lampshades which she constructed with barbed wire, for one. “We constructed these objects to resemble lanterns,” she says.

“Barbed wire is usually used territorially to fence people out, and it’s by definition sharp and dangerous to pass through. But in my salt sculptures it’s transformed, because it is coated with salt crystals, and it’s on the verge of being unrecognizable. It looks like vertebrae, something even quasi-decorative.”

And lately, she has really enjoyed coating pointe shoes, which were passed down to her from ballet dancers. “It was about taking something that was for me obsolete and bringing it back to my life and art.”

Some of her pieces also address the impact of mankind on the Dead Sea, which is rapidly receding at a rate of three feet a year.

The salt lake used to receive fresh water from rivers and streams from the mountains that surround it, and lose it by evaporation. The evaporation process, combined with its rich salt deposits, account for its extraordinary salinity, which is up to 33 per cent.

But in the 1960s, Israel built the National Water Carrier, an enormous pumping station on the banks of the Sea of Galilee, diverting water from the upper Jordan, the Dead Sea’s prime source, into a pipeline system that supplies water throughout the country.

Israeli and Jordanian companies also evaporate the Dead Sea’s water to harvest its rich minerals for export.

The Dead Sea is about 15 per cent more shallow than it was just half a century ago. It may continue to drop 330 feet over the next century.

Related posts

Rehabilitation Nation: Israeli Innovation On Road To Healing

Israeli High-Tech Sector 'Still Good' Despite Year Of War

Facebook comments