Prof teaches computers what motivates real people in the real world

Algorithms are everywhere, making decisions that affect all our lives, from traffic lights and bus timetables to Facebook and Spotify. Whether we realize it or not, we have all developed our own algorithms, and we use them on a daily basis.

We use an algorithm to tie our shoelaces, make a cup of coffee, sort laundry, drive a car or follow a recipe. An algorithm is nothing more than a precise list of step-by-step instructions. Algorithms that power lunar landings, banking and finance, robotics, autonomous cars, you name it, are all, essentially lists of instructions, albeit very sophisticated ones.

They may be executed by huge computers, but the algorithms themselves start life as ideas generated by human brains, and sometimes those ideas need a tweak.

Prof Inbal Talgam-Cohen, of the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, in Haifa, takes a particular interest in refining algorithms to become more effective, and to take account of what motivates real people in the real world.

She studies Algorithmic Game Theory, employing math and computer science models to understand how self-interest skews the way people interact with algorithms. Put simply, they think they can beat the system by telling lies.

Her work is rooted in the research by Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmström, for which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2016.

They were concerned with Contract Theory – the relationship between, for example, shareholders and top executive management, insurance companies and car owners, or a public authority and its suppliers.

And they tackled questions such as:

Should healthcare workers, and prison guards be paid fixed salaries, or should their pay be performance-based?

To what extent should managers be paid through bonus programmes or stock options?

Should teachers’ salaries depend on (easy to measure) student test scores or (harder to measure) skills such as creativity and independent thinking?

As a computer scientist, Prof Talgam-Cohen is addressing the same sorts of issues, but her interest is in what she calls “incentive-aware algorithm design” – how computers can help achieve better outcomes.

“When we’re designing an algorithm we can use tools from economics and from Algorithmic Game Theory to kind of anticipate what effect it’s going to have on the people it’s interacting with,” she says.

“Maybe we’ll redesign it, even giving up a little bit of what we’re originally trying to achieve with the algorithm, but in such a way that it will actually work in the real world.”

We are, ultimately, rational and selfish. We want the best for ourselves and our families. So we are not necessarily honest, straightforward and selfless in all our dealings with other people, let alone with computers.

Prof Talgam-Cohen recognizes that people will always try to manipulate algorithms. So her mission is to design them in a way that incentivizes all parties involved to strive for what she calls “fruitful cooperation” rather than the current default, when people trying to outwit the machine.

“Our aim is to design algorithms that better serve society,” she tells NoCamels, “by adapting them for the real word and taking account of things as they actually are.

“Algorithms are all around us, really influencing us, and making decisions for us, what we’re going to buy, what content we see, what opportunities we get.

“The problem is that classic algorithm design has not kind of taken that into account, the fact that it’s influencing and interacting with people, and people are going to react strategically in their own self interest.

“It doesn’t matter if the algorithm is doing the best thing for society, I’m still going to be rational and do what’s best for me.”

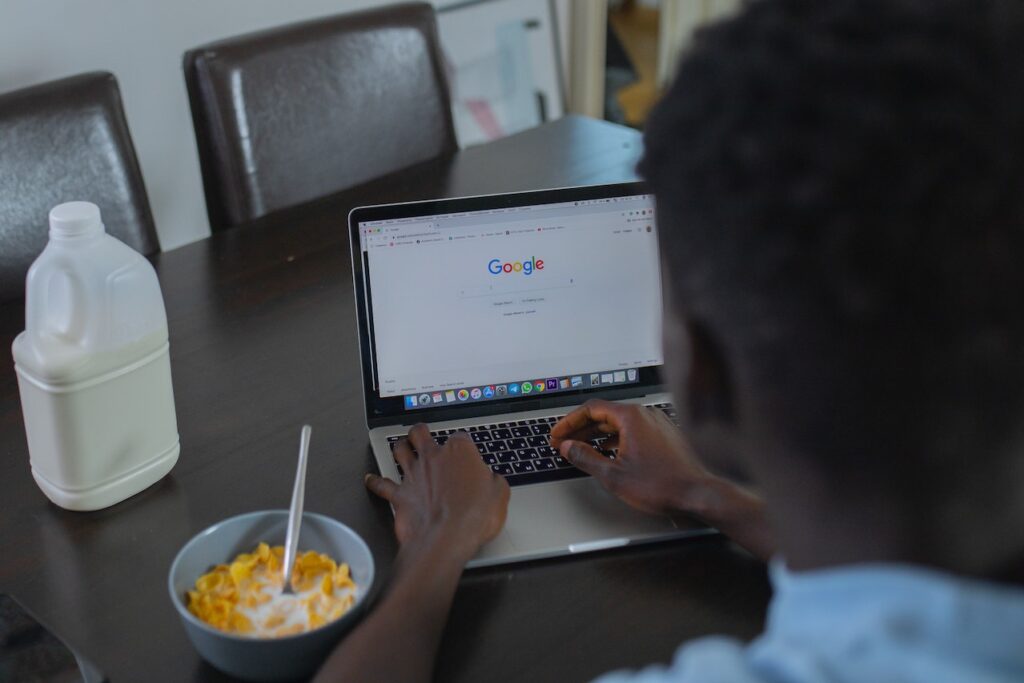

Google is a great example, she says. It runs powerful algorithms to rank websites. But people do whatever they can, buying links and using other “Black Hat” techniques to trick the algorithm into giving them a higher ranking.

We also find manipulation in the “real” world, such as the famous case of the badminton players in the 2012 Olympics. Four teams, from China, South Korea and Indonesia were thrown out of the women’s doubles competition for deliberately trying to lose their matches, so they’d be drawn against weaker rivals in the next round.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThey were disqualified for the offenses of “not using one’s best efforts to win a match” and “conducting oneself in a manner that is clearly abusive or detrimental to the sport”.

Prof Talgam-Cohen says her aim is to incentivize people to cooperate rather than manipulate the system.

“With a more principled, theory-based approach, we can maybe avoid the cat and mouse game. We can design the algorithm to begin with so that the people can put their effort into achieving outcomes that are positive for society.”

She identifies examples of the practical applications of her work as motivating people to protect the environment more, achieving a fairer allocation of school places, and introducing performance-related payments on freelance platforms.

“Say you’re choosing a school for your kids,” she says. “Will you tell the truth? It’s not clear. The top school may be your first choice, but you know there’s a lot of demand, so you may opt for the third or fourth as a safety net.

“So you’ll try to manipulate your answer. If we take that into account, we can really make a huge difference.”

She says sophisticated parents will manipulate more and less sophisticated parents will manipulate less, so it’s important to level the playing field.

“You can design the allocation algorithm so you can tell parents that if they lie, there’s no way they’ll get their child into the school they prefer.”

In environmental protection she says the key problem is the fact that people don’t have the right incentives.

“What we want to do is incentivize land owners not to pollute so much and maybe to plant trees on their lands. They’re beginning to use money for that and use payment-based incentive schemes but I don’t think they’re optimized yet. What we do best in computer science is to optimize and we can really take these systems and make them better.”

She also sees potential on Fiverr, TaskRabbit and other online marketplace for freelance services.

“When people go on these platforms, to get a logo designed, for example, they’re writing it on a computational platform. So why not use the power of computation to really get the contract, to get it much more optimized than it is today,” she says.

“A lot of prices now are set by algorithms, what’s not being realized yet is how you can tie the prices to the performance.

“For example, if somebody is designing my website, maybe I don’t just want to pay them, I want to say that I expect to see an increase in visitors to my website.

“And for every extra visitor, over a baseline before the redesign, there will be an agreed payment.

“The freelancing agent is working in a really complex environment, juggling different contracts for different employers and employers are also juggling a lot of contracts with different providers.”

“Theoretically, you could use a classic contract, but in reality these platforms are so different from a classic economic setting, with tons of data that the algorithm could use to personalize the contract.”

Her work recently earned her five years of funding from the European Research Council, designed to help scientists who excel early in their careers to pursue their most promising ideas.

“It’s amazing in terms of the opportunities that it opens up,” she says. “I can hire researchers who have expertise, and already know, a lot about algorithms and incentives, and machine learning, and optimization and build an even stronger research group than I have today.

“I envision one team working on optimizing the contracts, another team will do the same thing, but really think about simplicity, and robustness. And one team will think about how to resolve differences if you have contracts that contradict each other.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments