Israeli researchers have discovered that a rare tumor found in the fossilized tail of a young dinosaur that lived in Canada over 66 million years ago indicates the same, rare disease that affects humans today, particularly in children.

The tumor is part of the pathology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), a rare, painful disease known to affect humans and specifically children under the age of 10.

The findings by researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU), alongside international colleagues, indicate that the disease is not unique to humans and has survived through the long evolutionary process, from dinosaurs to humans, according to a university statement.

A study of the research, led by Dr. Hila May of the Department of Anatomy and Anthropology at TAU’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research, was published this week in the science journal “Scientific Reports.” Professor Bruce Rothschild of Indiana University, Professor Frank Rühli of the University of Zurich and Mr. Darren Tanke of the Royal Museum of Paleontology also contributed.

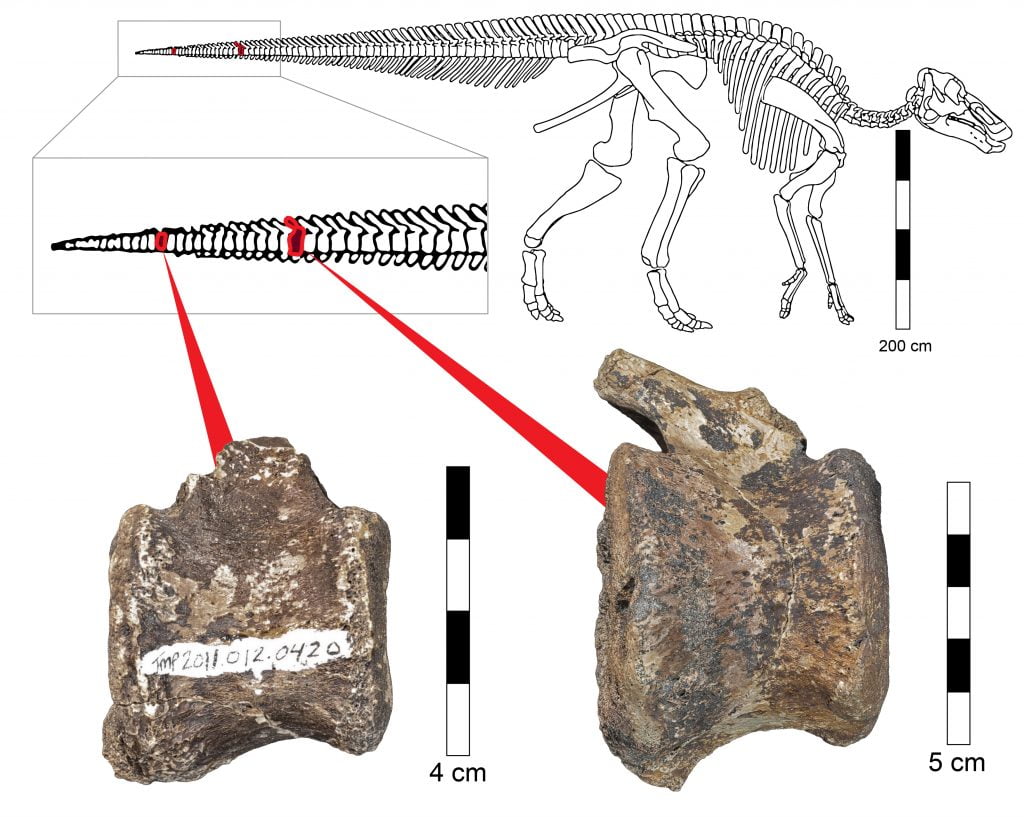

“Researchers in North America studying dinosaur fossils identified large cavities, evidently created by tumors, in two tail vertebrae of a young dinosaur discovered in southern Alberta,” Dr. May explained in a university statement. “The dinosaur belonged to the genus Hadrosaurus, also known as ‘duck-billed dinosaurs’ – herbivores common almost all over the world about 66-80 million years ago.”

The discovery was made at the Dinosaur Provincial Park in the city.

The specific shape of the cavities grabbed the attention of the researchers because they “were extremely similar to the cavities produced by tumors associated with the rare disease that exists today in humans,” Dr. May added.

The fossils were sent for inspection using advanced micro-CT scanning at the Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute at TAU’s Dan David Center for Human Evolution in the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, which is located at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.

“The micro-CT scanner generates images with a very high resolution of up to a few microns,” explained Dr. May. “Using it to scan the dinosaur vertebrae we were able to form a reconstructed 3D image of the tumor and the blood vessels leading to it. The image confirmed in a high probability that the dinosaur did indeed suffer from LCH.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“The surprising findings indicate that the disease is not unique to humans and that it existed in different species over 60 million years – through the long evolutionary process,” she went on.

“These kinds of studies, which are now possible thanks to innovative technology, make an important and interesting contribution to evolutionary medicine, a relatively new field of research that investigates the development and behavior of diseases over time,” noted Professor Israel Hershkovitz of TAU’s Department of Anatomy and Anthropology and Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research.

Professor Hershkovitz has studied malignant tumors in dinosaurs and assisted in the identification of the LCH tumor in the current study, according to the university.

This is the first time this disease has been identified in a dinosaur, May said.

“Most of the LCH-related tumors, which can be very painful, suddenly appear in the bones of children aged 2-10 years. Thankfully, these tumors disappear without intervention in many cases,” she explained.

Understanding diseases that affected dinosaurs may also shed additional light on their biology, daily living, and the environments in which they thrived, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports.

“Evolutionary Medicine researchers try to understand why certain diseases have survived through millions of years of evolution and to discover their source, in order to ultimately develop new and effective ways to address them today,” Professor Hershkovitz said.

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments