Israeli scientists at Tel Aviv University (TAU) announced on Tuesday that they have answered a “major question” about how melanoma (a serious type of skin cancer) cells go from limited growth in the epidermis, the skin’s outer layer, to becoming lethal.

Professor Carmit Levy and Dr. Tamar Golan of TAU’s Department of Human Genetics and Biochemistry at the Sackler Medical School revealed newly published research that highlights the key role fat cells play in metastasizing melanoma which then spreads and attacks patients’ vital organs.

“What makes melanoma change form, turning aggressive and violent?” Levy asked in a university press statement. “Locked in the skin’s outer layer, the epidermis, melanoma is very treatable; it is still Stage 1, has not penetrated the dermis to spread through blood vessels to other parts of the body and can simply be removed without further damage.”

SEE ALSO: 4 New Developments In Cancer Research, Detection, And Treatment From Israel

“Melanoma turns fatal when it ‘wakes up,’ sending cancer cells to the dermis layer of skin, below the epidermis, and metastasizing in vital organs,” she explained.

“Blocking the transformation of melanoma is one of the primary targets of cancer research today, and we now know fat cells are involved in this change,” Levy added.

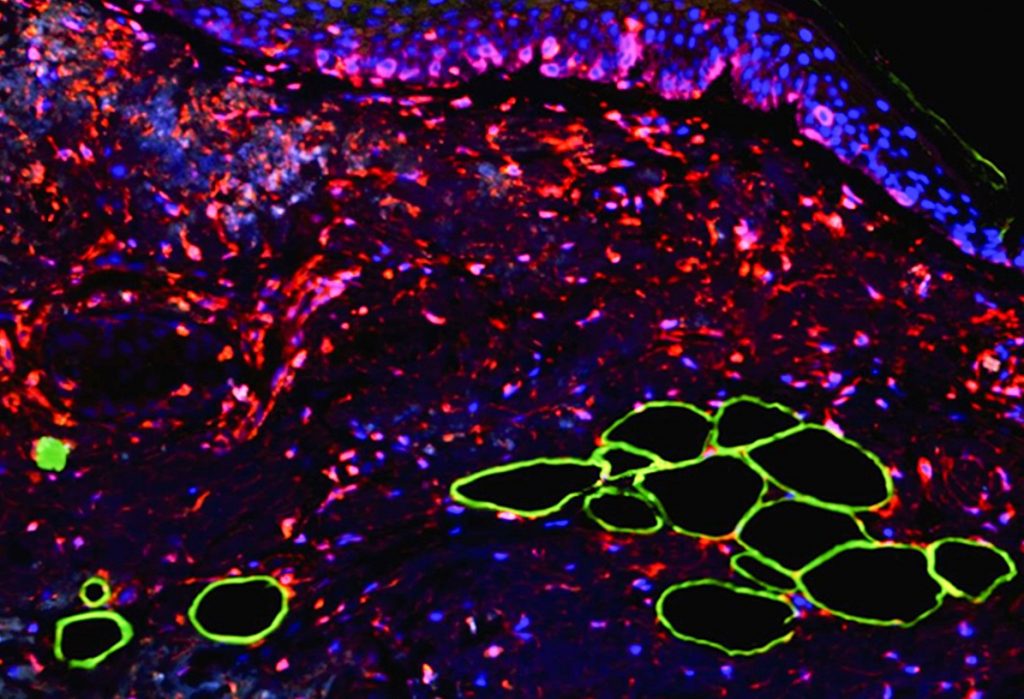

In their study, published on Tuesday in “Science Signaling,” a peer-reviewed scientific journal published weekly by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Levy and Golan showed how fat cells transfer proteins called cytokines, which affect gene expression, to the melanoma cells, stimulating their growth. The study is the cover story in the July 23, 2019 edition.

“Our findings…reveal a molecular link between fat cells and metastatic progression in melanoma that might be therapeutically targeted in patients,” the scientists wrote.

The transformation is a result of a chain of reactions, Levy tells NoCamels, which begins when fat cells “throw” cytokines to the melanoma. These cytokines repress the expression of a gene called miRNA211 in the melanoma cells, which causes an increase in expression of a receptor for the protein known as TGF Beta.

“Then, the melanoma cells suddenly express the receptors for TGF beta,” Levy continues. “Once there is a receptor on the membrane of a melanoma, then [it] can be sensitive to TGF Beta in the environment. The TGF Beta will then push the melanoma very rapidly to become aggressive and metastasize.”

After the melanoma cancer cells invade into the dermis, they can then metastasize through the lymph system, the researchers write.

The scientists’ research was conducted in collaboration with senior pathologists Dr. Hanan Vaknin of the Wolfson Medical Center, and Dr. Dov Hershkowitz and Dr. Valentina Zemer of the Tel Aviv Medical Center. In the study, the researchers examined dozens of biopsy samples taken from melanoma patients at the two centers and observed a “suspicious phenomenon,” namely fat cells near the tumor sites.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“We asked ourselves what fat cells were doing there and began to investigate,” Levy explained. “We placed the fat cells on a petri dish near melanoma cells and followed the interactions between them.” This led the team to establish the link between the fat cells and the transformation of the melanoma cells.

The discovery also indicates that the process is reversible, which Levy says is “very highly encouraging.”

“When we removed the fat cells from the melanoma, the cancer cells calmed down and stopped migrating,” Levy noted in the university statement.

A trial in mouse models showed similar results. “When miRNA211 was repressed, metastases were found in other organs, while re-expressing the gene blocked metastases formation,” the university statement read.

The researchers then experimented with therapies known to inhibit cytokines and TGF beta, but which have never before been used to treat melanoma, in hopes of getting on a path to finding a potential drug based on the new discovery.

“We are talking about substances that are currently being studied as possible treatments for pancreatic cancer, and are also in clinical trials for prostate, breast, ovarian, and bladder cancers,” Dr. Golan said in the press statement. “We saw that they restrained the metastatic process, and that the melanoma returned to its relatively “calm” and dormant state.”

SEE ALSO: Israeli Oncologist Offers Hope With New Treatment For Some Pancreatic Cancer Patients

Though the development of a drug may be years away, according to Levy, she is hoping the next step will be a collaboration to begin that process.

“I really want to have something to offer patients, or people who are at high risk for melanoma,” Levy tells NoCamels.

Levy says the scientists have not registered a patent. “It will just be a feeling that you contributed something to the world,” she explains.

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments