Israeli scientists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem say they have developed a new drug that could become part of a future cure for acute leukemia, more specifically Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), after initial lab tests on mice showed a 50 percent success rate.

AML, an aggressive cancer of the blood and bone marrow, is the second most common type of cancer diagnosed in adults and children, but is found more frequently in adults. The known treatments are several decades old and the survival rates depends on a number of biological factors, including features of the disease and the age of the patient, but generally, approximately 25 percent make it past five years.

The cancer causes a patient’s myeloid (bone marrow tissue) cells to form or immature blood-forming cells not normally found in the blood, and which do not function like normal cells, according to an explainer on Healthline, medically reviewed by University of Illinois-Chicago, College of Medicine.

These blasts can stop the body from making healthy, normal cells which will lead to a “lack red blood cells that carry oxygen, platelets that prevent easy bleeding, and white blood cells that protect the body from diseases… because their body is too busy making the leukemic blast cells.”

SEE ALSO: Israeli Researchers Say They Can Reprogram Cancer Cells Back To Their Pre-Cancer State

Israeli Professor Yinon Ben-Neriah from the Hebrew University’s School of Medicine-IMRIC-Immunology and Cancer Research who led the study and published the findings last week in the scientific journal Cell, says that to date most of the available biological cancer drugs used to treat this form of cancer target only individual leukemic cell proteins.

“However, during ‘targeted therapy’ treatments, leukemic cells quickly activate their other proteins to block the drug. The result is drug-resistant leukemic cells which quickly regrow and renew the disease,” he explained in a statement.

The new drug developed by Ben-Neriah and his team “functions like a cluster bomb,” according to a Hebrew University statement. “It attacks several leukemic proteins at once, making it difficult for the leukemia cells to activate other proteins that can evade the therapy.”

The scientists say the drug also accomplishes two important steps: it eliminates the need for additional drugs, “reducing cancer patients need to be exposed to several therapies and to deal with their often unbearable side-effects,” and has the ability “to eradicate leukemia stem cells,” which they say “has long been the big challenge in cancer therapy and one of the main reasons that scientists have been unable to cure acute leukemia.”

The developments are promising as “the standard care for AML hasn’t changed in 45 years,” Ben-Neriah tells NoCamels via e-mail. “Patients are still treated with 50-60-year-old chemotherapy combination.”

Even as new biological drugs have been introduced, it is still in combination with chemo, he says, and “the only cure option today for this patient is bone marrow transplantation, reserved for younger patients having an appropriate donor and even many of these, still relapse.”

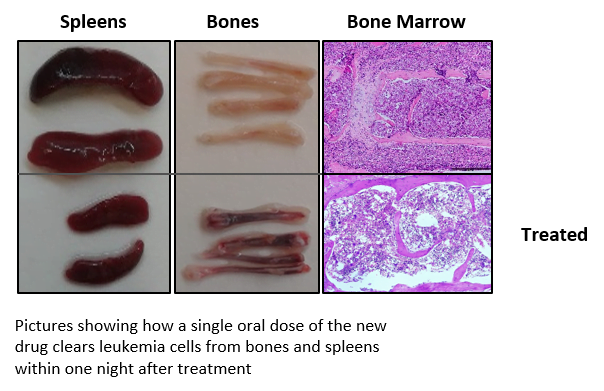

Ben-Neriah said he was thrilled to see “dramatic change even after a single dose of the new drug” administered to the lab mice. “Nearly all of the lab mice’s’ leukemia signs disappeared overnight,” he said.

The professor tells NoCamels that the team was now looking into the cure rate and researching why the drug worked on some and not others.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“While all the leukemia mice initially responded to treatment, about 50 percent relapsed a few weeks after cessation of treatment whereas the others showed no leukemia signs for many months, nor has their bone marrow cells initiated leukemia after transplantation, indicating the elimination of leukemia stem cells,” he says.

SEE ALSO: Israeli Scientists Develop New Method To Detect Breast Cancer With Up To 95% Accuracy

The rights to the drug were recently bought from Hebrew University’s technology transfer company Yissum by the US bio-pharmaceutical company BioTheryX, which develops therapies for hematological malignancies and immune dysfunction.

Yissum and BioTheryX have partnered before for previous research findings developed by Ben-Neriah. In 2016, the two signed a licensing and research agreement for the selection and advancement of clinical drug candidates with hematological malignancies.

The trial was to be based on a study by Ben-Neriah and his team that found that inhibiting a type of enzyme in the body, CKI-alpha, “induces several tumor suppressor pathways including a new type of DNA damage response and p53 activation [a tumor suppressor protein].”

“This provides a novel approach to treat a wide range of cancers, in particular selective types of hematological malignancies,” Yissum said in a 2016 statement.

That same year, Ben-Neriah won the Rappaport Prize, an annual award honoring scientists “for groundbreaking or innovative research which has the potential to advance the health of mankind.” Ben-Neriah was awarded the prize for excellence in biomedical research for his ground-breaking findings, among others, on the relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer and the treatment of leukemia.

“Prof. Ben-Neriah and Prof. Alex Levitzki developed the first effective inhibitors of the Bcr-Abl protein, which eliminate chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells. These studies ultimately paved the way for the development of Gleevec, the flagship drug for treating CML disease,” the Rappaport Prize wrote.

The next steps for the current research on Acute myeloid leukemia, Ben-Neriah tells NoCamels, involve applying for FDA approval for phase I clinical studies to find how to prevent drug resistance and relapse, first in AML mice and then in patients.

“The first patients on a clinical trial will be AML patients who are refractory to existing treatments, then other AML patients and patients having other hematological cancers bearing the oncogenes abolished by the drug (like multiple myeloma and lymphoma patients),” he explains to NoCamels.

“We will probably not start first with leukemia patients having p53 mutations, as native p53 is one of the important targets for the drug,” he says, adding that he and his team are now developing a test “for predicting the leukemia response using a small blood sample.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments