Researchers Regenerate Heart Cells In What Could Be A Huge Breakthrough For Heart Disease Treatments

Heart attacks are one of the most common and deadly human ailments, with a cardiovascular event striking once every 34 seconds in the United States. Yet few know that following a heart attack, a good portion of the heart muscles remain damaged, leaving patients at risk for future heart failure and other serious cardiovascular diseases. And despite the brevity of most cardiovascular events, human heart cells rarely regenerate (unlike blood, hair and skin cells), which led researchers at the Weizmann Institute in Israel to question whether heart cells can be programmed to reverse damage in the heart.

Prof. Eldad Tzahor and Dr. Gabriele D’Uva succeeded in both understanding why heart cells don’t regenerate in repairing damaged heart muscles in mice. These insights may be key in formulating a treatment for heart conditions related to and following heart attacks, that is if the researchers succeed in regenerating heart cells in human subjects as well.

Animals can do it, so why can’t we?

Using his knowledge of embryonic development, particularly as it pertains to the heart, Tzahor set out to understand why humans are naturally unable to regenerate their own heart cells. Animals, like salamanders and zebrafish, are able to regenerate heart cells, and though they don’t usually live through heart attacks (if they have any) their hearts are able to naturally recuperate from minor cardiovascular events.

SEE ALSO: One Heart Sometimes Beats As Two Dozen: New Study Could Improve Heart Disease Treatment

“There are various theories why the human heart cannot do that,” study co-author Prof. Richard Harvey told The Guardian, “one being that our more sophisticated immune system has come at a cost.”

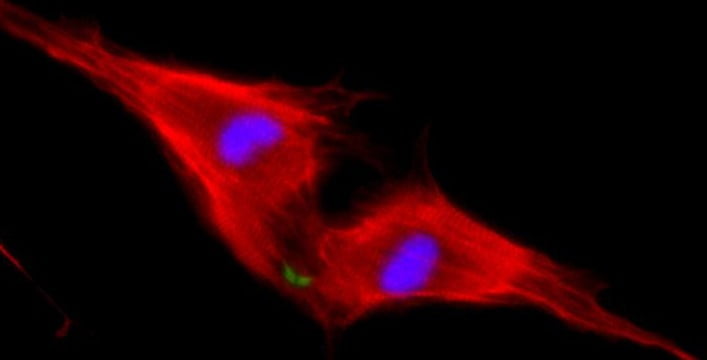

Tzahor and D’Uva studied how a protein central to heart development, ERBB2, and a growth factor called Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) work together in heart generation in mice. ERBB2 is what is known in biology as a “specialized receptor,” or a protein that transmits external messages into a cell, and it partners with NRG1 to get its message across to the cell. The team observed that heart muscle cells called cardiomyocytes can be regenerated in newborn mice, but just seven days later, the mice no longer generated new cardiomyocytes.

ERBB2: The missing link

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThrough the process of elimination, the team discovered that the reason newborn mice were able to regenerate heart cells, while seven-day-old mice were not was due to the amount of ERBB2 present on the cellular membranes. Isolating the responsible factor, they created mice that didn’t have any ERBB2, and therefore a very small number of cardiomyocytes, only to find that their heart cells were too thin and that they could not reproduce essential cardiomyocytes. When they reintroduced ERBB2 into the adult mice, they found that there was an overabundance of heart cells created, resulting in a giant heart leaving little room for blood to enter.

These findings led the research team to pose the following hypothesis: If ERRB2 could be activated for a short period in an adult who suffered a heart attack it may be possible to regenerate heart cells and reverse muscular damage. Surprisingly, the team saw positive results in adult mice that had experienced an induced heart attack, experiencing complete heart regeneration within several weeks.

“The results were amazing,” Tzahor said in a press release. “As opposed to extensive scarring in the control hearts, the ERBB2-expressing hearts had completely returned to their previous state.”

SEE ALSO: Three Cups Of Coffee Per Day Protects From Heart Disease

Live imaging and molecular studies revealed the fascinating way that this happens: The cardiomyocytes revert to an earlier form, something between their embryonic to adult cellular state, allowing them to divide and differentiate themselves into new heart cells. The research team made a huge breakthrough in potential heart damage treatments by discovering that a metered dosage of the ERBB2 protein could actively promote cellular regeneration in the heart by reverting cells back to their embryonic state.

Tzahor and his team will continue researching the effects of introducing ERBB2 into existing heart disease treatments (which include injections of NRG1), but the results remain preliminary. “Much more research will be required to see if this principle could be applied to the human heart, but our findings are proof that it may be possible,” he says.

Prof. Eldad Tzahor’s research is supported by the Louis and Fannie Tolz Collaborative Research Project; the European Research Council; and the estate of Jack Gitlitz.

Photos: Ammmy Garcia/ Glitterina DotCom/ Weizmann

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments