As the sun sets over the ruins of Caesarea’s Roman theatre, Arab minarets and Byzantine moats, a scarce few miles away, in Mazor Robotic’s offices, what may be the future of surgery sees a new dawn.

Mazor Robotics, an Israeli company with subsidiaries in Florida (USA) and Münster (Germany), last year launched robot-guided surgery. And not just any surgery: their system, Renaissance, takes on the particularly delicate field of spine-surgery.

Related articles

- Minimally Invasive Treatment May Soon Be Possible For People With Mitral Regurgitation Disorder

- The Innovative Blood Monitoring Device Worn On Wrist That Steve Jobs May Have Liked

To this day, it’s been used for tens of thousands of implants worldwide, has launched Mazor Robotics into NASDAQ and has proved an overall success. NoCamels visited their offices in Caesarea to learn if all surgery before Renaissance will now look Medieval.

Renaissance: A surgeon-dependent robot

Inside Mazor’s premises, I’m received by CEO, Ori Hadomi, along with International Service Group Manager, Amir Suidan. I’m introduced to the robot, its history and functioning.

The brand Renaissance harbors both hardware (the robot itself) and software (the program on which the operation is planned). How does Renaissance add precision to surgical interventions? By pre-programming the operation on a virtual image of the patient’s spine.

The surgeon pinpoints on the virtual spine (a replica of the patient’s) the exact point on which they want to intervene and with which tools. This information is transmitted to the robot, nestled on the patient’s back. After receiving the pre-planning, the little bot will automatically readjust its position to the one needed by the surgeon to carry out the operation.

Renaissance is not a cane come to yank the surgeon off stage. While designing it, Mazor were careful to not “over-robotize it.” They are aware of the importance of keeping the planning and performance of the operation in the surgeon’s hands. “It’s very sexy to say that in the future robots will replace surgeons,” Hadomi admits “I don’t only think that it won’t happen, I don’t even recommend it [should] happen.”

The operation, stage I: Pre-planning

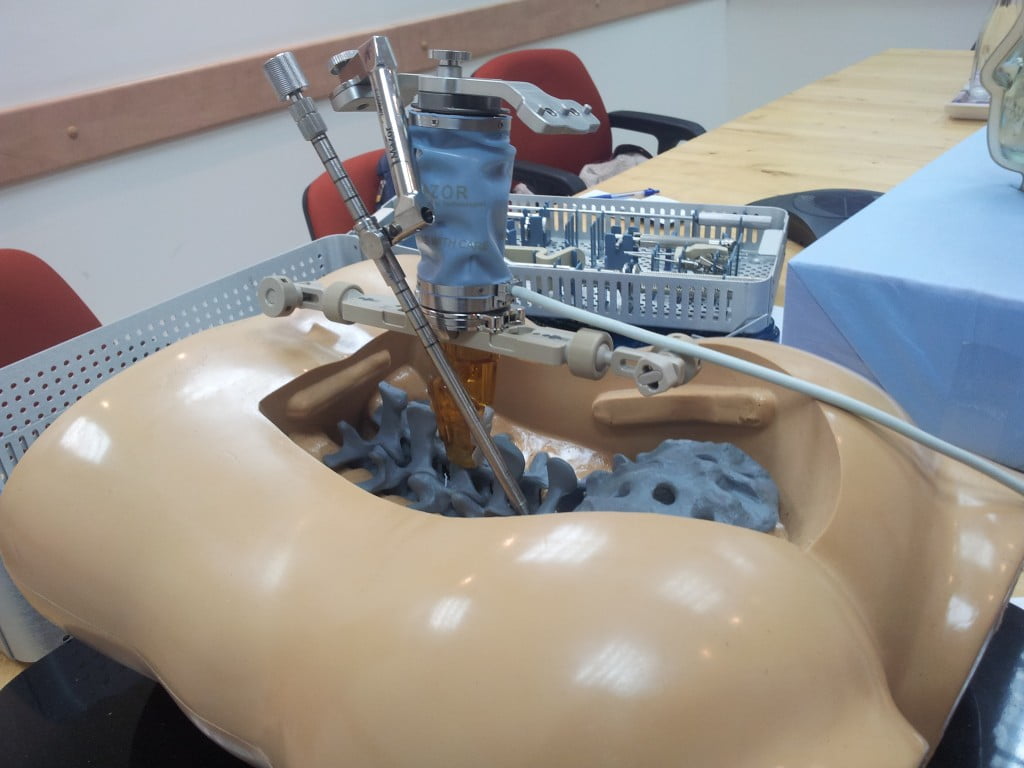

Amir Suidan travels all over the globe to teach hospitals how to use Renaissance. Likewise, Suidan offered NoCamels a demonstration.

Our mock-operation was to be carried out on a clay model. “The patient,” Suidan contextualizes, “has a very common diagnostic: spondylolisthesis.” I believe him. “One vertebra is more protruding than the one below. This provokes back and leg pain.”

In spine surgery, an implant is inserted to stabilize two vertebrae. The challenge is introducing the screw into a very thin bone corridor. Surgeons run the risk of hitting the spinal cord or the nerve canals. Both areas have significant clinical impact. CEO Hadomi explains that before Renaissance, some 10 percent of the cases ended with misplaced implants and about 5 percent, with long-term neurological damage.

A Renaissance-based operation begins with a CT scan of the patient’s spine. This creates the 3D representation of the spine on the computer screen upon which the surgeon will pinpoint through three different angles the exact niche into which he wants to insert the implant.

The surgeon then indicates which screw he wants to implant into the spine. “Taking into account all the data, the software proposes a solution, a guide for how to mount the robot,” Suidan explains, “Our system’s compliant with any type of implant company.”

The operation, stage II: Performance

The robot is placed on a bone-mounted platform on the patients back. Now comes its moment of glory: the robot, whizzing, humming and whirring, almost imperceptibly moves into the position it needs for the surgeon to carry out the operation.

“The virtual spine isn’t a static model,” Suidan points out “the patient will have rearranged his spine slightly from the time the CT scan was done until he’s on the bed.” Throughout the operation, two similar images glow side by side on the screen: the preoperative CT and a live X-ray image taken from the OR. The aim of the operation is to match both images.

Suidan defines the robots actions as “executing the preoperative plan.” He is very enthusiastic: “We’ve made the planning! We know what implants we’re using! You can make sure you have all the pieces before you start the operation! No more: ‘Oh! We don’t have one of these! Give me whatever you have…!”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeComing soon: the brain

In July 2012, Mazor Robotics received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) marketing clearance for creating a Renaissance brain surgery robot. Hadomi explains they plan on launching it this year.

“The brain is not very different from the spine,” Suidan explains to NoCamels.”With the spine, we want to enter the bone, remain on the bone and not touch any nerves. It’s the same with the brain. If there’s a cancerous cell inside the brain, the surgeon chooses which part of the cranium to go through to target the tumor.”

I’m also given a demonstration. This time the patient is a grinning clay cranium. The operation is also pre-operatively rehearsed on a 3D scan. The biggest difference with a spine intervention, as the mocking skull on the operation table points out, is that a cranium is round. The trajectory can enter through many points, unlike spine which is a straight line. Still, it’s the surgeon who designs the operation.

Hadomi adds that at Mazor they are also currently working on more applications and technologies. “We are focusing on spine,” he remarks, “we want to bring more robotic technologies to expand the type of solutions we can offer in spine.”

“We’ve saved 200-400 lives”

Hadomi, after studying at the Technion, joined the company in 2003 through his acquaintance with the founder, Professor Moshe Shoham. “This company was founded to develop robotic solutions for pathology (hip, knee, spine…) and traumatology. But we couldn’t afford to be so diverse and focused on the area which maximized our valuable position.”

Mazor Robotics started off as a small startup. Although nurtured on seed investors and venture capital, they soon became publicly traded in NASDAQ. At NoCamels, we’ve followed the evolution of Renaissance since the announcement of its completion in June 2012.

Hadomi is proud of his company’s creation: “Renaissance has been used in 4,000 operations and zero cases have long term nerve damage. Compared to that 5 percent of the statistics, there are probably some 200 to 400 patients whose lives we saved.”

As of winter 2012, Mazor had sold 42 systems around the world, 21 of which in the US. The system costs about $1 million per unit, a significant investment for the hospital. Its target markets: the really complex spine procedures and the minimally invasive spine procedures. Renaissance can also help improve scoliosis, a very common spine deviation in teenagers.

Invasive spine procedures can entail long recovery time and risk of infection. Renaissance doesn’t only decrease all this, it also reduces hospitalization time. This is in hospital’s best interests because less hospitalization time means more available beds for other patients.

Israeli President Shimon Peres visited Mazor Robotic’s offices just a few weeks before NoCamels. Mazor decided to surprise him: They asked surgeons worldwide to prepare a short video on their smartphones talking about their experience with Renaissance.

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TvdpGc2WmN8′]

A happy company

Ori Hadomi, in an interview to The New York Times, spoke about the importance of an open, happy and communicative workspace. “I believe my role is not to make people work but to give them the right working conditions so that they will enjoy what they do.”

I leave Mazor Robotics and, for the sake of contrast, decide to take a walk round Caesarea’s archeological site. Strangely aware of my own scoliosis, I imagine the Byzantine boats which in centuries past had glided into the stone harbor like Renaissance navigates into the spine and somehow it all seems more in the past than ever.

Photos: Courtesy

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments