With a history dating back thousands of years, Israel is home to significant religious sites, landmarks and some of the oldest cemeteries in the world. Locals and tourists alike visit the country’s multitude of cemeteries to pay their respects to loved ones or reflect on the past.

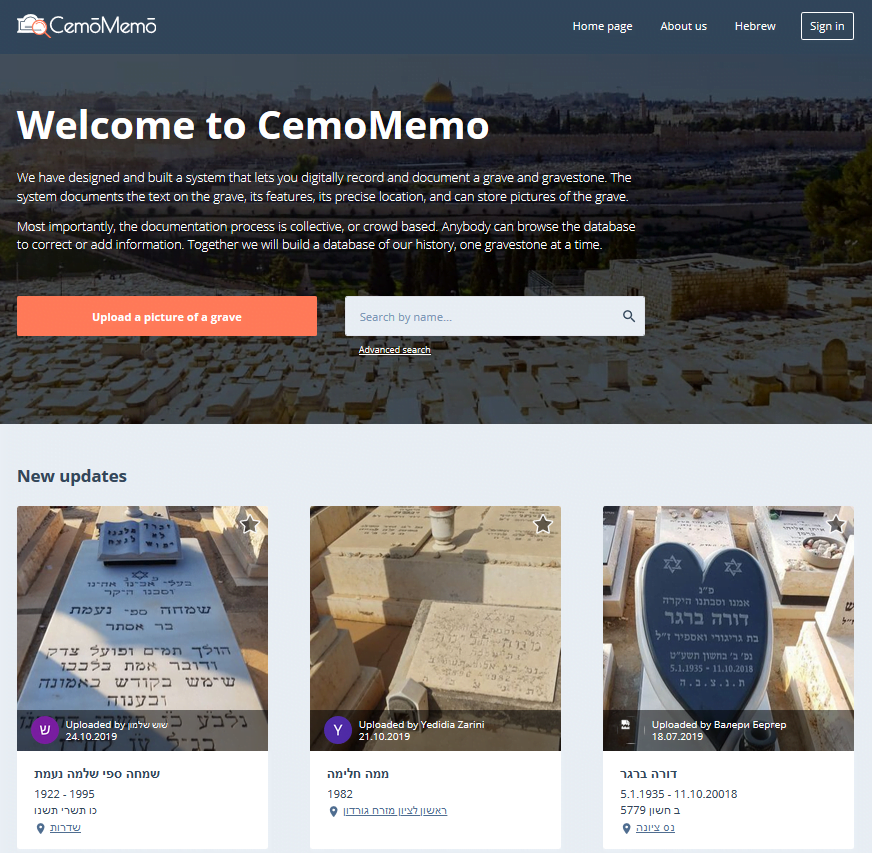

CemoMemo, a collaborative documentation platform for gravestones, is undertaking the digitization of headstones to turn cemetery visitations into unique historical explorations.

The project started as a collaboration between the Software Engineering and the Land of Israel Studies departments at Kinneret Academic College. “The idea was to develop an online searchable database of cemetery headstones,” Dr. Michael J. May tells NoCamels. Dr. Efrat Kantor, a historian specialized in the study of collective memory, approached Dr. May with the plan to digitally record graves in Israel to aid remembrance, research, as well as preservation.

SEE ALSO: National Library, Facebook Launch Joint Project To Identify IDF Soldiers In Rare, Historic Images

Studying how communities memorialize their loved ones, Dr. Kantor finds historical value in every headstone. “You can understand a community’s view of itself, its socioeconomic level and its outlook on the world, based on how it writes down information on the headstone of the people they want to remember,”, Dr. May explains. “And therefore, often the headstones reflect the community, the rememberers, more than they reflect the person who is dead.”

But CemoMemo does not stop at only being a useful tool for researchers. It also says it wants to turn cemeteries into more accessible sites for “dark tourism” – the concept of traveling to places that relate to death or tragedy.

“It’s not a new idea,” May explains. “People go out on tours in countries of their roots, visit cemeteries of great leaders, rabbis, or founders of Kibbutzim.” In Israel for example, the Holocaust memorial site Yad Vashem is considered one of the country’s main destinations.

Bringing another academic partner on board, Dr. Uzi Einstein from the department of Tourism, CemoMemo began to add more tourist-friendly features to the system. Today, the Android app allows travelers to navigate to specific graves of interest and helps them to arrange their visits.

Combining the historical and the touristic value in one platform, the operators claim to provide “many more fields and research capabilities than any other system out there.” Currently, there are two other active players in the field of headstone digitization. One of them is the genealogy platform MyHeritage, which claimed earlier this year to have completed the digitalization of all of Israel’s graves and cemeteries, documenting a total of 1.5 million gravestones in 638 cemeteries throughout Israel in partnership with the application BillionGraves. The second player is called Find A Grave, run by the commercial genealogy company Ancestry.com.

Like CemoMemo, both platforms are crowdsourced and enable users to upload pictures of graves. But there are “major differences,” May tells NoCamels. “First, our system is more open and allows users to edit and modify information. The second difference is that those systems are built for genealogy research, and therefore they do not provide any other information besides names and dates.”

With a focus on the study of family ancestral lines, genealogy platforms do not fully disclose the content written on a headstone. But for CemoMemo, this is exactly the point where it starts to get interesting.

The system documents the text on the grave, its features, its location, in addition to photos. “We are taking the headstone as a historical document, which means that you can search for details and even answers to complicated questions,” May says.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeAimed at giving users the opportunity to get a sense for a past community, CemoMemo’s database has extensive support and search features. “If you want to know how many children under the age of eleven drowned in the Kinneret before 1950, you can find them because you can assume that people used to write the cause of a person’s death on the headstone”.

For CemoMemo, building a system that is community-based was important. to help people discover their own histories. Today, the platform has around 650 active users who have documented more than 1,200 graves in 75 Israeli cemeteries.

“We decided to focus on cemeteries that are not in big cities like Haifa or Tel Aviv,” says May. “We began with the smaller ones, the ones in kibbutzim or small towns, ones that don’t have active community maintenance or support.” Through this, CemoMemo achieves what it calls “digital preservation.”

One of the first documented cemeteries on the database was one in Rosh Pina in northern Israel, May recalls. “It has a lot of history, but it is based on a mountainside and in the past few years it has been physically falling apart. Erosion has been causing the cemetery to shift and many graves are tumbling down very slowly. So we went there and began to record what won’t be there anymore in 30 years.”

The platform is also able to store multiple pictures per grave, so that not only decay, but also refurbishment can be recorded over time.

To avoid any distraction from its academic value, the founders are eager to keep CemoMemo a non-commercial endeavor and to continue managing it with research grants. “This is not an attempt to build a business – it’s an attempt to build a research project that will give value to everyone,” May says. “We refer to it as the ‘Wikipedia of Graves’.”

To build an active community of grave digitizers, CemoMemo reaches out to towns, local authorities, local history enthusiasts and high schools, which have begun using the platform with students for educational purposes.

To extend the scope of the system, CemoMemo says it wants to open up its platform to other countries and even religions. The team says it began to correspond with Jewish communities in Macedonia and Lithuania.

In the long term, CemoMemo says it plans to enhance its location services and enable users to build their trips to specific graves according to reasonable walking routes. Short term goals include the implementation of OCR (Optical Character Recognition) to automatically detect the content on a headstone, and the improvement of search features.

Since CemoMemo started as a senior student project and launched publicly in June, the team of academic staff and students has grown to include two web developers and one Android developer, a former student, who work continuously improving the system.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments