“Fish to disappear by 2050?” This sensational headline was the result of a 2010 report by the United Nations Environment Program, declaring that over-fishing and pollution had nearly emptied the world’s fish stocks —a disaster for over a billion people around the world who are dependent on fish for their main source of protein.

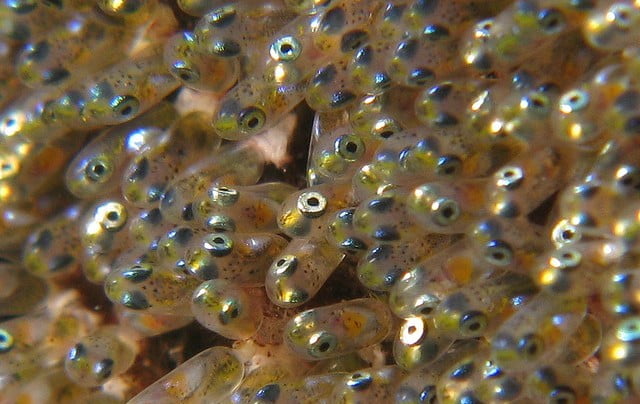

Now, a new study by Dr. Roi Holzman and Victor China of the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University has uncovered the reason why 90 percent of fish larvae are biologically doomed to die mere days after hatching. The study, published in “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” comes to the surprising conclusion that it is the “stickiness” of water that is the reason why so many fish larvae perish, leaving only a marginal proportion to populate the world’s oceans.

Pinpointing the biological flaw

Holzman based his study on the problematic nature of fish reproduction. Nearly all fish species reproduce externally, meaning they release and abandon their sperm and eggs into the water. The fertilized eggs then hatch in the water within a couple of days and the hatching larvae must sustain themselves.

Discover the self-sustaining farms created using fish and hydroponics

“We thought, something is going on during this period, in which the proportional number of larvae dying is greatest,” Holzman said. “Our goal was to pinpoint the mechanism causing them to die. We saw that even under the best controlled conditions, 70 percent of fish larvae were dying within the two weeks known as the ‘critical period,’ when the larvae detach from the yolk sac and open their mouths to feed. What was going on?”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeLike eating soup with a fork

The physical structure of the larvae and their flawed interaction with their physical environment provided the answer Holzman was looking for. Over the course of two years, he and his doctoral student Victor China observed fish larvae at three significant points in their development (at eight, 13, and 23 days old). They found that the “stickiness” of the water — the viscosity of the surrounding ocean water — was hampering the larvae’s ability to feed.

Meet the seven alternative energy companies with solutions to fuel the future

“All that determines the larvae’s feeding ability is their interaction with the surrounding water,” said Holzman. “Because the water molecules around you have weak electrical bonds, only a thin layer sticks to your skin — a mere millimeter thick. If you’re a large organism, you hardly feel it. But if you’re a three-millimeter-sized larva, dragging a millimeter of water across your body will prevent you from propelling forward to feed. So really, it’s all about larval size, and its ability to grow fast and escape the size where it feels the water as viscous fluid.”

The researchers found that in less viscous water, the larvae improved their feeding ability. “We conclude that hydrodynamic starvation is the reason for their dying,” said Holzman. “Imagine eating soup with a fork — that’s what it’s like for these larvae. They’re not developed enough at the critical point to adopt the constrained feeding strategy of adult-sized, better-developed fish.”

Armed with this knowledge of the larvae’s biological flaw, the researchers are currently patenting a solution to maintain higher survival rates among fish larvae and find a solution to the looming fish crisis. The research was published in “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.”

Photos: Rennett Stowe/ Tel Aviv University

Related posts

Resilient And Nutritious New Plant-Based Milk Aims To Make A Splash

Chocolate From Cultivated Cocoa Comes Without Environmental Toll

Plastic Fantastic: Startup Takes PVC Back To Its Crude Oil Roots

Facebook comments