Former US President Donald Trump famously challenged the voting system that brought his rival Joe Biden to power in November 2020. He claimed the software in electronic voting machines could flip votes between candidates.

Brazil’s former President Jair Bolsonaro contested the outcome of the election in October 2022, after losing narrowly to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. He claimed a bug in the software used by the all-electronic voting system had robbed him of victory.

The challenge for any election organizers is to prove to the loser that they lost.

The winner will always be happy they won, but it can be a lot harder to persuade the loser that they did so fairly and squarely.

Traditional paper ballots and current versions of electronic voting clearly don’t do that, says Shai Bargil, CEO of an Israeli startup called Sequent.

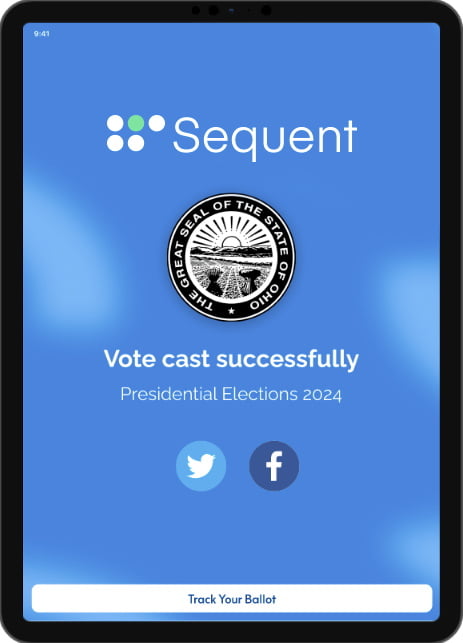

He says they’re changing that with smartphone voting.

The technology they’ve developed is based on advanced cryptography and allows voters to cast a ballot from their device at home or on the move, secure in the knowledge that it is completely tamper-proof.

Every vote cast is verifiable thanks to what’s called “zero knowledge proof”, a highly-advanced mathematical protocol that guarantees the validity of information – in this case a vote – without revealing the nature of the information, in this case who the vote was cast for.

It means elections remain both private and secure, while providing mathematical evidence that votes have been cast and counted accurately – from ballot box to results day.

It costs a fraction of the price of existing voting systems, and it is more accessible, which means more people are able to vote.

The software that powers the system is also “open source” – publicly accessible for anyone to inspect or challenge – unlike the so-called “blackbox” technologies used by most e-voting platforms.

There is a huge and growing market for e-voting, but Sequent says it alone offers the combination of verifiable votes – backed by its cryptography – and open source software.

Its online voting system has so far been used in over 200 elections across 10 different countries in both the private and public sector – from local government elections to those in private organizations such as unions, universities, associations and political parties.

“When you vote, you want to make sure your ballot was cast correctly and counted correctly. On paper, it’s very, very simple. You see your paper ballot, you know what you marked, and you have a lot of electoral observers and supervisors who verify that the ballot is counted correctly,” says Bargil.

“With digital voting, you cannot verify the software, you cannot make sure that the software actually took your ballot and marked it correctly and counted it correctly. That’s been the big problem with digital voting for the last 20 years.

“We solve this problem. We have developed a software that verifies end to end that each ballot was cast and counted correctly.”

Bargil’s twin passions are technology and democracy. He spent six years developing combat systems for the Israeli Defense Forces, followed by a Master’s in political science at Tel Aviv University and a stint as a political advisor at the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. He founded Sequent in June 2021.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“The problem is very simple,” he says. “It’s 2023 and most of us are still voting on paper. We don’t have digital voting in polling stations, and we don’t have digital voting from mobile devices at home.”

Digital or e-voting has been around since the early 1990s. Belgium introduced electronic voting machines in 1991, Brazil in 1996, India in 1999, Venezuela in 2004 and Estonia in 2005.

The US has electronic voting in many states. In line with many other countries, the machines also create a paper ballot.

“Even if you vote in the polling station, digitally on a voting machine, it generates a paper ballot that can be counted and verified. So it’s more like a marking device than a voting machine,” says Bargil.

Sequent builds on new advances in cloud computing, open source software and cryptography – notably the zero knowledge proof jointly invented by Israeli-American computer scientist Shafi Goldwasser and Italian Silvio Micali.

Bargil is challenging bigger, well-established voting companies, among them Simply Voting and Smartmatic.

“We are a startup and startups bring new concepts, new technology, new systems to the market. This industry has been ruled by companies that are a little bit outdated, and hasn’t been disrupted for a long time.

“Now there’s a new startup with cryptographic technology and open source software that says, ‘Hey, you know what? We can do stuff differently’. Why? Because we understand what needs to be done in the next 10 years, rather than what’s been done in the last 10 years.”

Online voting has huge advantages for a vast and sparsely populated country like Canada, where voters may have to travel long distances. An online vote costs $2 compared with $11 for a ballot by mail.

Israel, a tiny country by comparison, could also benefit. It held five elections in under four years, at an estimated cost of $165 million each, and took the hit to the economy of a public holiday.

Trump was able to contest the 2020 election, says Bargil, because nobody knows what goes on inside the Dominion Voting Systems machines that were used to record votes.

“It’s a blackbox system. Nobody knows how the system operates and the election results cannot be verified.”

Canada, France Australia, Philippines, Denmark, Iceland and the United Arab Emirates are among the countries closest to adopting online voting, says Bargil.

“We are not trying to convince governments to move from paper to digital. We’re just saying, if you decide to move to digital voting to online voting, this is the way to do it.”

He says he’s speaking to Quebec, Canada, about using Sequent technology for municipal elections and to the state of Western Australia about online voting for people with disabilities. Ultimately, he hopes Sequent will be used in national elections.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments