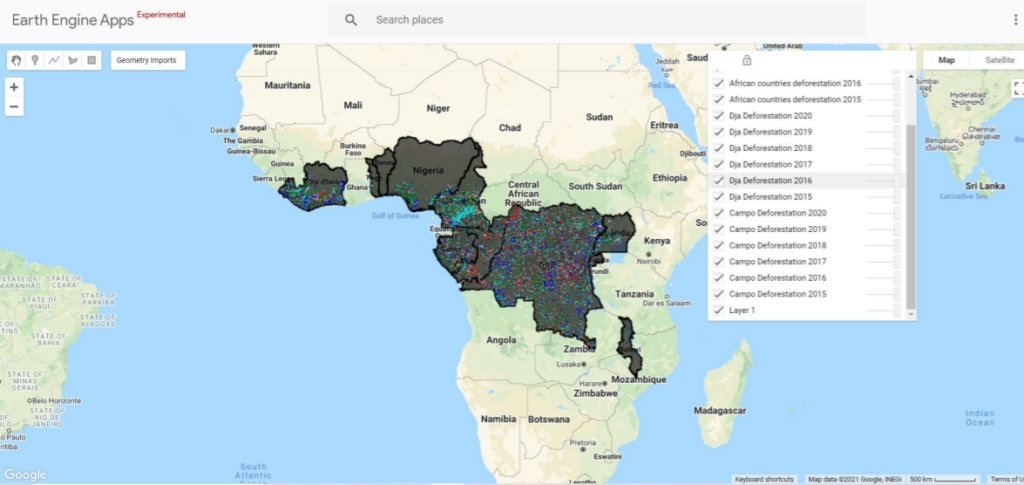

The team of Israeli entrepreneurs and scientists behind Albo Climate, the startup that analyzes satellite imagery with deep learning to map and monitor carbon sequestration in nature-based projects, has partnered with Mauritius-based firm Tembo Power to produce high-resolution carbon monitoring models of vulnerable tropical forests in several Sub-Saharan African countries.

The maps produced by Albo will be used to evaluate ecosystem health and monitor the areas for deforestation, as well as generate high-quality carbon offsets.

The two companies will begin the collaboration by developing carbon credits from two national parks in Cameroon, which need protection against deforestation. These parks, totaling 786,000 hectares in size, face increasing threats as a result of logging, poaching, mining, agricultural activities, and coastal infrastructure development. Given the current deforestation rates, the two forests may lose 6,000 ha a year, which translates to 3.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent a year

Jacques Amselem, co-founder and CTO at Albo, tells NoCamels the Tel Aviv-based company is currently in the process of producing the first maps for the project.

“We started this very strategic partnership with Tembo, a company that created hydropower projects in Sub-Saharan countries in Africa. Now they are developing all kinds of projects related to forestry and deforestation. It’s a very good match between this company and us. We are starting with the two very big projects and there should be others,” he explains.

“They were looking for technologies like ours,” he added.

Amselem says that the companies already have contracts with several African countries, including Uganda, to create models, which will have a “significant impact.”

The maps show how much carbon is being sequestered per pixel. Each pixel is 10 by 10 meters or even smaller.

The maps “can really visualize carbon sequestration and that can really help jumpstart a lot of projects for sequestering carbon within nature because there’s a lot of transparency and a lot more sense of ownership. In each area, you can really see the improvement and those who are investing can feel that there’s an impact. Those who are working the land can show them that there’s a real measurable impact,” explains Ariella Charny, Chief Marketing Officer at Albo.

The expected income from the carbon offset projects will involve, amongst other activities, expanded support of ranger services and surveillance systems by the forest management of Cameroon, as well as maintaining the park’s boundaries. In addition, the generated income will be used to support local communities, Albo said.

“Tembo’s goal is to position our subsidiary Tembo Climate in full compliance with the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets led by Mark Carney and Bill Winters, advocating for the extensive use of technology to address global warming, and are delighted to bring Albo’s cutting edge approach to the African continent,” said Tembo founder Raphael Khalifa in a statement, “We see carbon development as an ideal addition to our more traditional and established clean power business in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Projects in South America

In May, Albo Climate partnered with the Universidad De Las Americas (UDLA) and Fundacion Futuro, both based in Ecuador, to produce a productivity and carbon stocks map of the area of the Chocó Andino UNESCO World Heritage Site as well as develop a Monitoring, Reporting & Verification (MRV) Methodology for the use of remote sensing in tropical mountain forests.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThe partnership “offers a crucial opportunity to launch the use of remote sensing technologies to scale carbon sequestration projects, making a real dent on climate change,” stated Dr. Marco Calderón, CTO of Albo and Associate Researcher at Deakin University in Australia and Universidad de Las Américas in Ecuador.

In addition to producing an AI model and mapping of the region, Albo and UDLA’s MRV methodology proved crucial in expanding the use of satellite-based technologies across other tropical forests, Albo said.

Albo’s groundbreaking technology isn’t only being used to map out carbon stocks,. There are also other nature-related projects on the horizon. Amselem mentioned that Albo is beginning a project with the UDLA along the Amazonas River on the border between Ecuador and Peru. According to Amselem, gold can be found in illegal gold mines in this area and miners are using mercury to collect it. Eventually, he explains, many of the miners end up throwing the mercury into the river, where the fish eat the mercury, and locals who catch and eat the fish end up getting sick. Albo is working to create maps related to where this mercury can be found so that the general population can avoid it.

“In order to understand where the fish would go and who’s eating them, it’s very unpredictable. We use satellite imagery to understand the river patterns and also to show deforestation in the area, which can impact the river,” adds Charny.

“It’s basically the same kind of technology we are using, but we’re applying it to other uses,” says Amselem.

The mission

Meanwhile, global loss of tropical forests contributed to about 4.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year (or about 8-10 percent of annual human emissions of carbon dioxide), according to the World Resources Institute.

Finding the right way to measure carbon emissions and verifying the amount of CO2 removed, or sequestered, in forests and farms is a difficult process. Albo’s technology applies AI and deep learning algorithms to satellite radar imagery to make it easier for landowners to measure their carbon stocks and sell certified carbon credits, and for companies to start purchasing these credits.

“Based on our calculations, we are able to quantify the amount of CO2 that is removed from these areas,” Amselem says of Albo, which was found just two years ago. The company does this in the framework of the Paris Agreement, the legally binding international treaty on climate change adopted by 196 Parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in December 2015 and put into practice a year later. “The idea is to provide incentives and compensations to landowners who use various agricultural practices.”

Amselem is adamant that every member of the Albo team is there because they are passionate about what they are doing, he also says the company’s technology can only make an impact if it is open to everyone.

“We want to make it scalable and just open it to anyone that can get on the platform and get compensated for changing their practices,” he says, “We believe [our technology] is the right way to make an impact on the planet. If we keep it on a small scale, there is definitely some impact. But then we want to come with our Israeli chutzpah and say we dare to do this and you should too. The point is to say that everybody needs to get in on this. And then we will have a larger, more meaningful effect on the climate.”

Related posts

Resilient And Nutritious New Plant-Based Milk Aims To Make A Splash

Chocolate From Cultivated Cocoa Comes Without Environmental Toll

Plastic Fantastic: Startup Takes PVC Back To Its Crude Oil Roots

Facebook comments