The creators of a new treatment for blocked veins say their technology has the potential to revolutionize the treatment for a medical problem that affects millions worldwide but has been largely left unchanged for decades.

Veinway CEO and co-founder Jordan Pollack tells NoCamels that chronic venous disorders – a term covering a gamut of issues from varicose veins to pulmonary embolism – affect just under 10 percent of the global population and can greatly impair overall health and quality of life.

Among these disorders is blocked veins caused by blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – blood clots deep within the body. And successfully unblocking these veins, usually in the legs, has proven to be an unanswered challenge.

Pollack says that healthcare systems are not really set up to deal with patients with this issue, as it has not been a priority for them.

Patients with blood clots, he claims, are often brushed off with compression stockings, which gently squeeze the legs to stimulate blood circulation, or anticoagulants, which thin the blood. Neither of these, he says, is really a permanent or fully effective solution.

Indeed, the US Center for Advanced Cardiac and Vascular Interventions says that stockings do not actually dislodge already formed clots, while top American hospital the Mayo Clinic says that blood thinners do reduce the risk of clotting but cannot prevent it altogether.

These blood clots have to be treated within two to three weeks, Pollack explains. After that, the clot transforms into scar tissue made up of collagen, a protein found throughout the body, and fibrin, an unyielding substance formed from the fibrinogen protein in the blood.

“You no longer have a vein essentially,” Pollack says.

When clinicians do try invasive intervention by inserting a stent to clear a clot, he explains, they use the same technique as for a blocked artery.

“But it’s a completely different procedure than in the arteries,” he says. “Trying to place a stent is often an exercise in futility and definitely frustration.”

Pollack tells NoCamels that physicians are simply not using the right tools to deal with blood clots, and are in fact still using methods from the 1980s – such as guide wires and balloons – to traverse the blood clot and open up the vein.

“I’ve seen a lot of MacGyver-like improvisations,” he says, referring to the ‘80s TV action hero known for his ad hoc solutions.

“I’ve seen all kinds of craziness because nobody’s given them the right tools that they need to be successful.”

He explains that for the past three or four decades, interventional vascular medicine has focused on arterial disorders, which have more immediate and serious ramifications than venous disorders.

“Veins are often called the forgotten vessels,” he says.

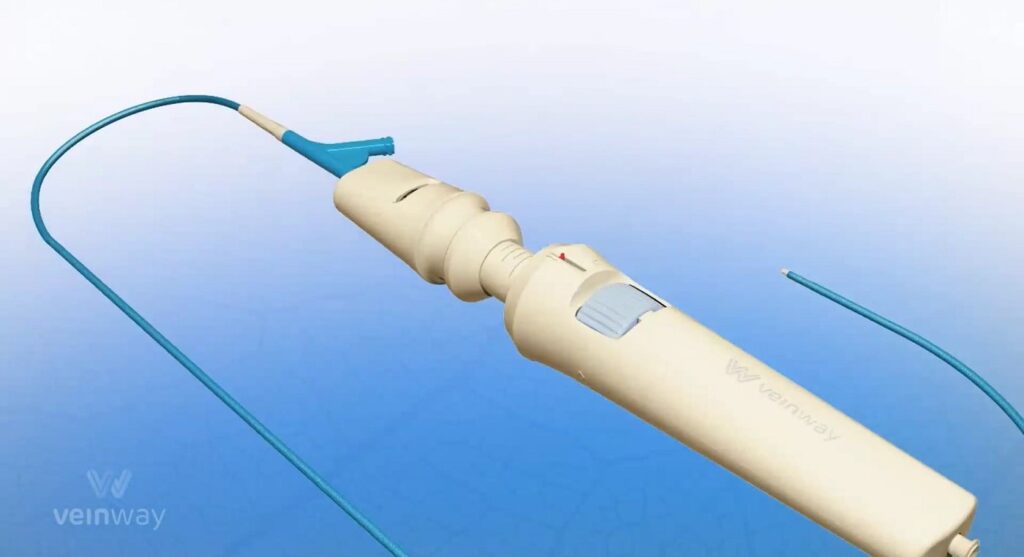

Veinway’s solution is called Traversa, a catheter-based device that uses proprietary technology to be more flexible than other incarnations and which is uniquely designed to deal with blocked veins.

“It’s the first device designed for crossing chronic occlusions in veins,” says Pollack, whose background is in biomedical engineering. “It’s designed to guarantee crossing quickly and safely.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThe device comprises an inflatable balloon and a steerable needle that can be bent by as much as 60 degrees, rotate a full 360 degrees and move both forward and backward.

“[This gives] three independent degrees of freedom,” he says.

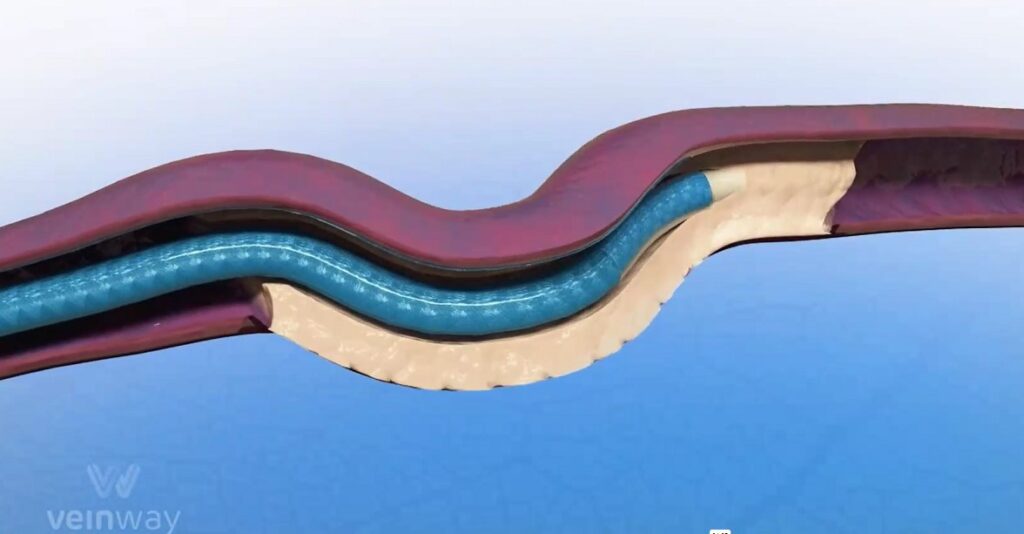

The needle is encased inside the balloon, which, when inflated within the vein, acts as anchor to hold the device in place while the needle advances forward through the blockage.

Pollack compares the consistency of the scar tissue in a blocked vein to a car tire or chewed-up piece of gum.

“We designed a device specifically for dealing with this kind of material,” he says.

Traversa has yet to begin full human trials, but Pollack says it has already been used in a small number of cases in the US and Europe in a compassionate use setting, when a patient is facing a grave or life-threatening disease and there are no other potential solutions.

He explains that in those cases, the device demonstrated its ability to break through blockages that no other intervention has been able to permeate.

“We crossed them quickly and reliably,” he says.

The Or Yehuda-based Veinway was established in 2020 at the initiative of the Israeli MedTech incubator MEDX Xelerator, whose core mission is to build and support “high impact” ventures that resolve unmet clinical issues.

“I took just the unmet need as a challenge,” Pollack recalls. “We learned about it and then we brainstormed and developed it ourselves.”

The young startup is now nearing the end of its Series A funding round. It has also had investment from the Israel Innovation Authority, the branch of the government dedicated to promoting the national tech sector, as well as MEDX and its long-term partner Boston Scientific, a leading US biomedical engineering firm.

And it is the US market that Veinway is primarily focused on, where Pollack says some 900,000 people are diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis every year (although there are similar levels of diagnosis in Europe too). The company hopes to have completed its human trials and be ready for market by the third quarter of 2025.

Pollack says that Traversa’s solution takes on even more significance when one considers the fact that venous diseases do not just afflict the elderly, and can be caused by a genetic disposition such as hypercoagulability, when the blood clots more easily.

And because many people suffer from these disorders while they are still young, treatments will stay with them for decades and not just a handful of years – making a reliable, long-term solution all the more critical.

“The healthcare system has to understand that these are patients that when you treat them… you’re going to have to follow them for their entire lives,” he says.

“It’s one of these things that I think there’s a lack of awareness around.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Facebook comments