Instead of sympathy and understanding, the worst terrorist attack in Israel’s history – when 1,200 people were murdered by Hamas on October 7, thousands more were wounded and hundreds were dragged into Gaza as hostages – was instantly followed by a massive explosion of global antisemitism.

In the US, the Anti-Defamation League reported that antisemitic attacks had “skyrocketed” by 360 percent since October 7, while in the UK, London’s Metropolitan Police reported a 1,350 percent rise in antisemitism in the country during the same time frame.

In France, the Council of Jewish Institutions in France (CRIF) said that 2023 had an almost 400 percent increase in antisemitic attacks compared to the year before, and in Australia, where chants of “gas the Jews” could be heard at a protest in Sydney just days after the attack in Israel, the Executive Council of Australian Jewry reported a 591 percent increase in antisemitic incidents since October 7.

For Tal-Or Cohen Montemayor, the founder and CEO of the CyberWell non-profit initiative to combat antisemitism on social media, immediate action was needed to fight this phenomenon, much of which she says is triggered by unfettered social media posts in the service of Hamas.

“We’re dealing with a different situation, especially because of the widespread use of social media and the way that social media has been exploited as a tool of misinformation and disinformation and psychological terror by Hamas,” Cohen Montemayor tells NoCamels.

“We need to understand that our regular strategies need updating, and we need to be active consistently until we beat this thing back. We can’t just leave it to take over.”

Cohen Montemayor founded CyberWell in mid-2022, concerned by what was then seen as an explosion of antisemitic sentiment on social media. It uses a proprietary AI system to scour the multitude of social media platforms for antisemitic content, flagging what it finds for a human to review and recommend action.

The Tel Aviv-based organization uses the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism to guide it, a definition adopted by more than 1,200 countries, local authorities and institutions since its inception in 2016.

Cohen, an attorney by profession and a specialist in online antisemitism and extremist movements in the US, was working in open source intelligence (data gathered from freely available information) when she saw what she terms “a consistent migration of antisemitic conspiracy theories and hardcore antisemitism [that had migrated] from the darker corners of the internet into mainstream social media platforms.”

At that point, she recalls, she began to consider the difference between the dark web and mainstream social media platforms, and realized that only the latter must abide by certain standards. Every major social media outlet has very clear rules against hate speech, including antisemitism.

“The mainstream social media platforms not only have policies, but they care about their reputations and they experience a lot of regulatory pressure,” she says.

By using those policies and that desire for a pristine reputation, Cohen Montemayor surmised, CyberWell could press the social media giants to take action against antisemitism on their platforms.

“The idea of CyberWell is marrying the worlds of technology and open source intelligence with digital policy compliance,” she explains.

Therefore CyberWell’s express mission, Cohen Montemayor says, is to drive the enforcement and improvement of digital policies on antisemitism across social media.

“We have a unique understanding about their policies and the way that their industry works when it comes to trust and safety,” she says of the social media companies.

“That makes the data that we collect actionable, and moves it beyond just a regular research recommendation into something that’s really implementable on the platform side.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

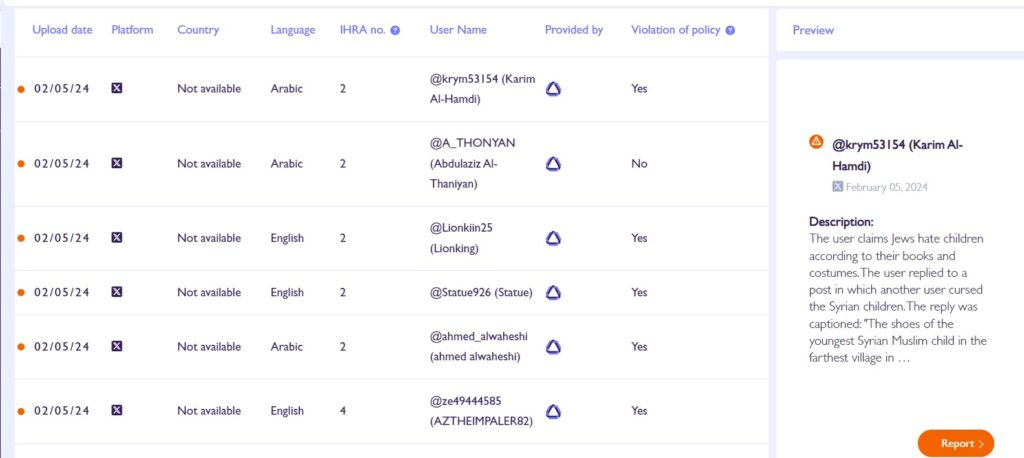

In 2022, not long after its launch, CyberWell unveiled the first ever database of online antisemitism, with examples of social media posts that the organization encourages users to report.

The database is constantly updated and appears as a list, with details about which platform the post appears on, its content, the name and country of origin of the poster and how many clauses of the IHRA definition it violates.

The list also shows whether a post has already been reported, whether it is in violation of a platform’s own digital policies and whether it has been removed by the platform.

One of the most common examples of online anti-Jewish hatred post-October 7, Cohen Montemayor says, is denial of the murders, rapes, mutilations and desecrations of bodies that occurred at the hands of Hamas terrorists as they rampaged through more than 20 Israeli communities for hours and in some cases, days.

And while she cites anecdotal evidence that such denial has already begun to spread in US middle schools, she insists that the battle is not yet lost.

In fact, she says, the social media platforms are responsive when shown breaches of their own terms and conditions.

“We’re monitoring the major platforms – Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and what was once known as Twitter – for antisemitism, but we’re also doing it with the analysis on which policies are failing to be enforced,” she explains.

“And because we’re coming at it from the policy perspective – the rules of the platforms themselves – it’s a lot easier for them to actually implement our analysis on their own platforms.”

This method, she says, has allowed CyberWell to become a trusted partner (a special status for non-profits working directly with social media platforms) of TikTok and Meta, the latter of which encompasses Facebook, Instagram and Threads. Furthermore, she adds, her organization is working behind the scenes with other platforms.

What is noticeable, according to Cohen Montemayor, is the sudden reach of smaller accounts that before October 7 had very little traction, but whose anti-Jewish and anti-Israel posts are now getting considerably more engagement.

“This could tell us one of two things,” she says. “One is inauthentic behavior i.e. bots that are amplifying this content, or it could tell us that there’s some kind of high level of engagement and algorithm recommendation on October 7 denial and distortion.”

In fact, Tel Aviv-based startup Cyabra, which monitors threats and misinformation on social media, told NoCamels in the immediate aftermath of the terror attack that it had identified more than 40,000 fake accounts supportive of Hamas across all platforms.

Ultimately, Cohen Montemayor is wary of singling out any particular platform as being more egregious than the others.

“Every platform has a problem with online antisemitism,” she says. “And every platform has its own unique risk when it comes to online antisemitism.”

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments