An Israeli startup has come up with a unique solution for a challenging medical procedure to treat problems in the bile duct, whose difficulty of execution can often lead to complications.

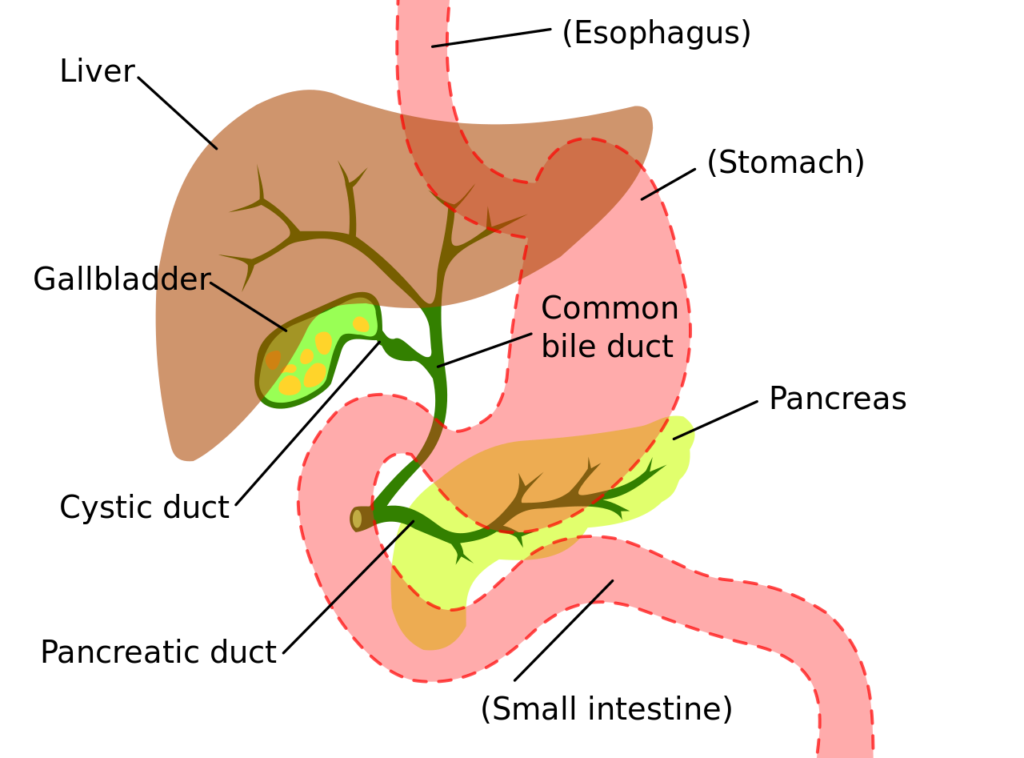

The bile duct is a tube-like structure that carries bile from the liver, where it is produced, to the small intestine, where it is used to help digest food.

Any treatment of issues within the bile duct, such as bile stones or other blockages, requires insertion of an endoscope – a tiny camera attached to a guidewire – during a procedure called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

This allows doctors to examine the area through imaging and involves inserting the guidewire through the mouth down into the duodenum – the first section of the small intestine – and then into the bile duct.

But the passage leading from the duodenum to the bile duct, known as the ampulla of Vater, also leads to the pancreatic duct.

And according to Samer Abboud, the CEO of medtech startup Swift Duct, the fact that the two ducts share the same entrance from the duodenum complicates an ERCP in around 1 in 5 patients.

“The whole process is done blindly without [the doctor] seeing what’s happening or where he or she is navigating,” Abboud tells NoCamels.

This means the guidewire can be inadvertently directed into the pancreatic duct, potentially leading to accidental damage, post-procedure complication and, in extreme cases, even fatality.

“The doctor may end up unintentionally in the pancreatic duct or bumping against the wall trying to successfully cannulate [insert a medical device into a body cavity] the bile duct. This increases the risk of pancreatitis, which is a pancreatic inflammation that we want to prevent,” says Abboud.

He explains that such cases can have a “severe impact” on the patient, causing a great deal of pain and often leading to a lengthy hospital stay, which also has financial and personnel implications for the healthcare system.

Swift Duct has devised a method of differentiating between the fluids produced respectively in the bile and pancreatic ducts, which ensures that the endoscope enters the former and avoids the latter.

“The fluids have different properties,” explains Abboud. “They have different colors, different viscosity and different electrical properties.”

It is these electrical properties that Swift Duct uses to direct the endoscope to the right destination.

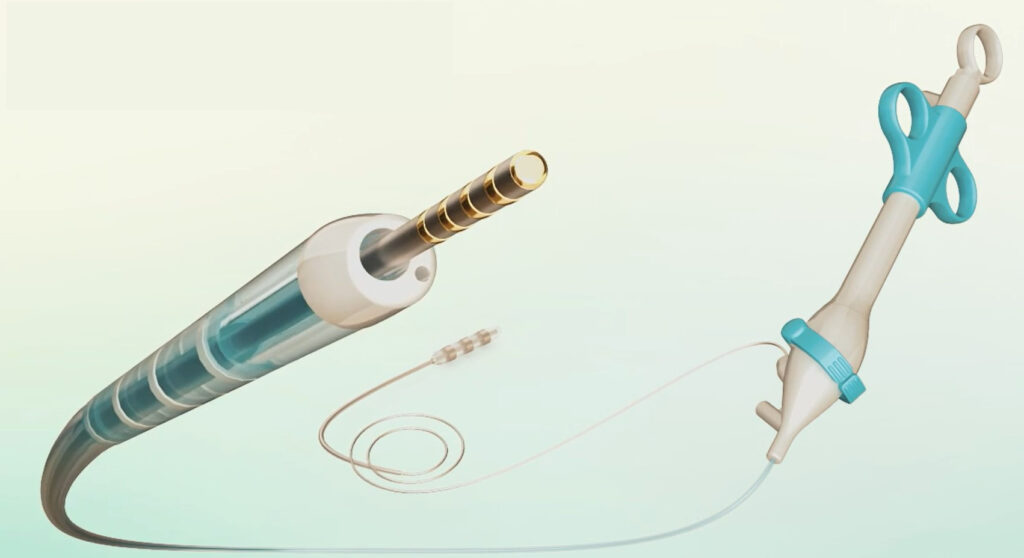

“We insert a wire, but instead of a passive wire, our wire includes sensors that can analyze the electrical properties of the fluids,” Abboud explains.

“And through this analysis, we indicate to the doctor where he or she is,” he says.

“If the doctor is getting closer to the dangerous area, we give alerts: ‘you’re getting into the dangerous zone.’ But if the doctor is getting into the safe duct, we say: ‘okay, go ahead.’”

The Swift Duct solution comprises two elements – the sensor that detects the differences between the bile duct and pancreatic duct fluids and a flexible guidewire that Abboud says allows doctors to move easily into the correct duct.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeOnce inside the ampulla of Vater, the sensor extends from the guidewire and into the duct, where it analyzes the fluid to determine whether it is in the correct place.

Together, he explains, the sensor and guidewire function as a kind of Google Maps for the small intestine.

“We do the whole procedure faster than usual because there is lots of trial and error involved in pushing against the walls, [which] not only increases the risk for pancreatitis but also prolongs the procedure,” he says.

So not only does the Swift Duct method reduce the time a patient is sedated and undergoing the procedure, according to Abboud, but it also allows physicians more time to attend to other patients.

It is, he says, an entirely original solution for which Swift Duct holds the patent.

The company was created in 2020 and today works with MEDX Xelerator, a medtech incubator and investor functioning with the support of the Israel Innovation Authority – a branch of the government dedicated to promoting the country’s high-tech sector.

Its founders – whom Abboud describes as “an engineer, a doctor and a business administrator” – created the endoscopic technology as part of a project they were assigned while attending a course on the development of medical devices.

The three interviewed a doctor who pointed out the need to improve the ERCP procedure, which they decided to make the focus of their project.

This led the trio to a meeting with a representative of Boston Scientific, a multinational producer of medical devices that works closely with MEDX, who facilitated a meeting at the incubator.

Both the IIA and Boston Scientific have since invested in the company, which is headquartered at MEDX’s northern Israel base in Sakhnin.

So far, Swift Duct has successfully completed its proof of concept and animal testing stages and is now conducting human clinical trials at three hospitals in Israel.

Trials at one of the three, Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya, have almost completely halted as the northern city is located just a few kilometers from the Lebanese border and presently considered unsafe due to the fighting with the Hezbollah terror group.

As a result, the trials are primarily taking place at Rambam Healthcare Campus in Haifa and world-renowned Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, the biggest hospital both in Israel and the entire Middle East.

Abboud expects that the two devices will be ready for market in the first half of 2026.

“We had lots of ideas at the beginning,” he says. “But we ended up with a very simple solution.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Facebook comments