An Israeli space startup working on a way of drawing oxygen from the moon’s soil has accidentally stumbled upon a carbon-free, green alternative for the production of steel and other metal alloys.

Helios was created in 2018 with the initial goal of producing oxygen on the moon so that spacecraft transporting items to the lunar surface would be able to travel more lightly and without the oxygen-heavy fuel needed to return to Earth.

The plan was to extract the oxygen from ore on the lunar surface through a chemical process, but they quickly realized that the carbon they needed was not found on the moon.

For hundreds of years, humans have used fossil fuels such as carbon to heat ore in order to extract iron, copper or other metals and minerals. This process, known as smelting, creates a chemical reaction that separates the metals or minerals from oxygen that binds them to the ore.

Without the availability of naturally occurring sources of carbon, the team went back to the drawing board. At this point, they found an unlikely but abundant source of fuel on the moon that none have thought to use before: sodium.

“We literally opened the periodic table and tried to figure out what other elements we could try,” Jonathan Geifman, co-founder and CEO of Helios, tells NoCamels.

“What immediately popped out to our chemical experts was the first column in the periodic table: the alkali metals.”

The startup also realized that burning sodium had the potential to address a pressing environmental issue down here on Earth, namely the copious amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted during smelting.

Geifman says that the team decided to start with the production of steel – the iron and carbon blend responsible for a sizable proportion of our carbon footprint.

“This is the one metal [alloy] that humanity produces the most – 10 times more than all of the other metals combined,” he says. Every ton of steel produced, he explains, also emits two tons of CO2.

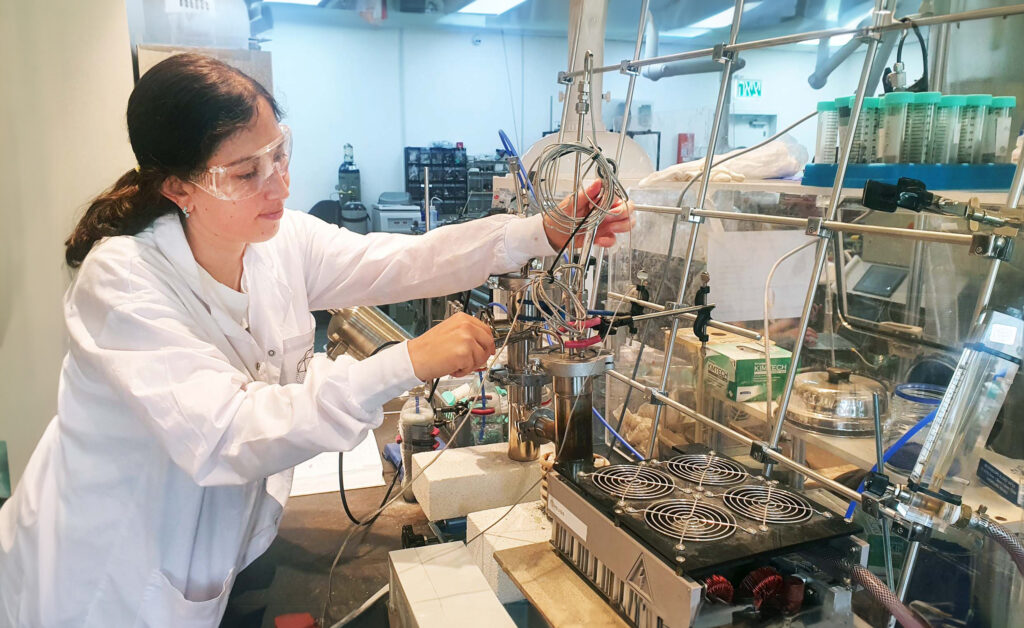

The startup says that its sodium-based method of producing steel can cut energy use by half and eliminate direct carbon emissions entirely.

“Our whole process requires less energy in comparison to how steel is produced today,” says Geifman.

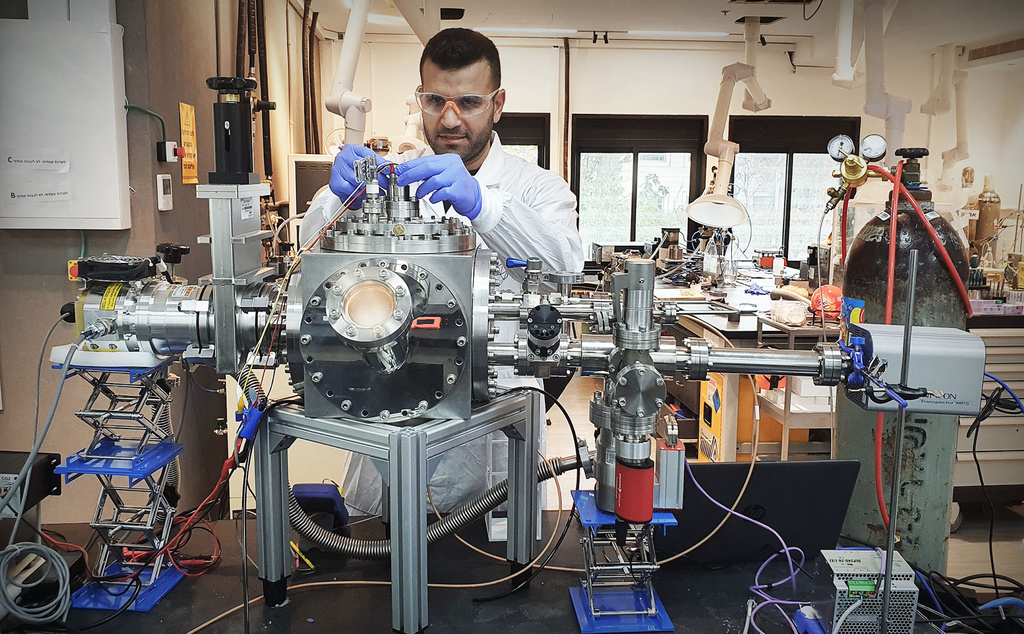

This is because the sodium used in Helios’ proprietary hardware only needs to be heated to 400°C (752°F) in order to separate the oxygen from iron in the ore. The oxygen then binds to the sodium, creating sodium oxide.

This sodium oxide can then be heated to 500°C (932°F), which releases the oxygen and allows the sodium to be used once again.

Carbon, on the other hand, needs to be heated to 1,400°C (2,552°F) to achieve the same effect. And while it still involves the process of combining with oxygen, it also causes harmful carbon dioxide emissions to be released into the atmosphere.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeHelios has raised $17 million thus far from government grants, mining companies such as Anglo American (one of world’s largest), angel investors and venture capital firms including Tech Energy Ventures and At One Ventures.

The startup, which is based in Kochav Yair in central Israel, is currently in the process of scaling up its technology.

It will demonstrate its capabilities next year when it completes its first pilot plant, which will be able to produce several tons of steel per day.

The startup then plans on selling and licensing its hardware to conventional steel mills, rather than competing with them.

“Our agenda is to decarbonize the industry, and we want to do this as widely as possible,” Geifman explains.

“If we’re just another steelmaker competing in the market, we wouldn’t be able to do that. But if we’re enabling the whole market to use our technology, that’s a way faster approach.”

Geifman says that commercializing his startup’s technology for the production of green steel is also the shortest route to financing and achieving the end goal of space mining.

Helios ultimately aims to source metals and other resources beyond Earth – whether on asteroids, comets or the moon – in order to preserve the planet and minimize the damage that humans are causing it.

At present, says Geifman, this is an extremely expensive process, and there is no metal on the planet that is so costly that it justifies traveling to the stars to mine them.

“We’re trying to pave a way for that to actually be economically viable,” he explains.

“There is a long road we need to take in order to get there, but someone has to do this.”

According to Geifman, it is uncertain whether future generations will have the same opportunity to do this as his company does now.

“As a species, we need to try and aspire for the ultimate sustainable solution and not just pass the problem onto the next generation without knowing what will happen.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Facebook comments