Today, there are around eight billion hens in the world, laying more than 1.6 trillion eggs in 2022.

And for farmers whose businesses depend on these egg layers, the inevitable male chicks that are hatched – roughly seven billion every year – do not have a fiscal benefit and are killed immediately.

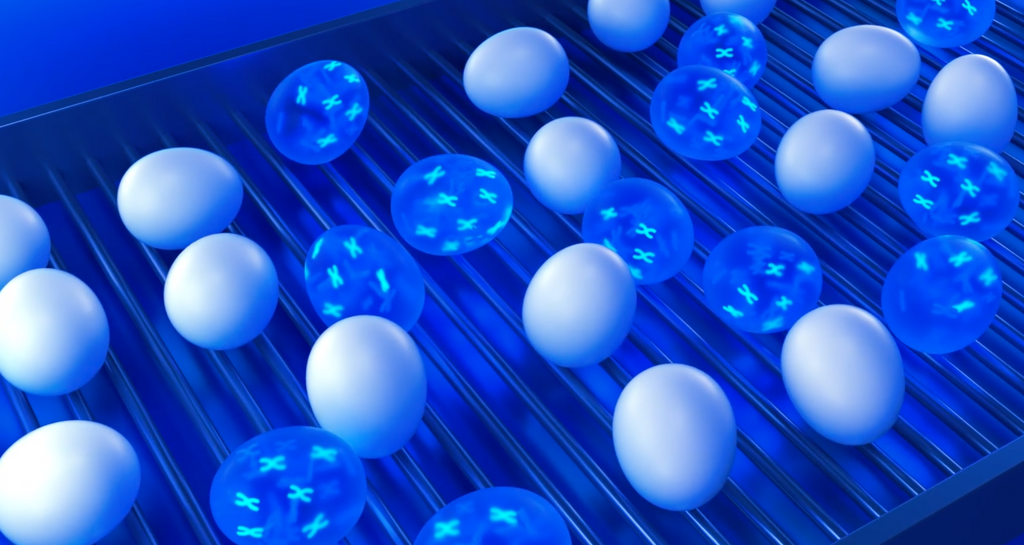

Israeli startup Huminn Poultry has developed a gene that stops embryos from developing into male baby chicks when the eggs are exposed to a simple blue LED light.

The gene was introduced to a group of chickens that the company dubbed the “Golda line.” Their eggs, which also include the gene, are incubated under a regular blue LED light for 21 days until they hatch.

By day three of the 21-day development, however, when the embryos inside the eggs begin to determine their sex – and while they are still just bundles of cells – the light triggers the gene to stop all further development of eggs containing male embryos.

The female eggs, on the other hand, go on to hatch and lay their own eggs.

A complementary technology identifies the undeveloped eggs that are subsequently removed from the incubator.

These undeveloped eggs are essentially pure protein that can potentially be used for animal feed and need not go to waste, says Eli Mor, president and co-founder of Huminn Poultry.

“We have hundreds of eggs that have been exposed to the blue light, and to date, not a single male chick has hatched,” Mor tells NoCamels.

He believes that if integrated into the DNA of the chicken breeds used by the world’s biggest breeders, the gene can prevent over 90 percent of all male chicks from being culled at birth.

“This phenomenon, I would say, is the most horrible and devastating in terms of animal welfare,” says Mor.

The startup is a subsidiary of Huminn, an Israeli company that uses gene editing to solve healthcare, nutrition and sustainability challenges. It believes that aside from avoiding a grisly fate for baby male chicks, its solution can also save a lot of money, time and labor.

Chicken eggs need to spend three weeks incubating, and it is only when they hatch that egg producers can actually determine their gender. To do so, they must manually sort the chicks – usually by gently examining the length of their wing feathers.

The cost of culling each male chick is a single dollar, but with nearly eight billion hatching each year, the cost rises to match the inhumane way in which they are killed.

Mor explains that male chicks that are killed cannot be used as a food source instead as they are of a different breed to chickens raised for poultry.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“These are completely different birds,” he says. “[Egg layers] are very efficient, smaller and eat less. All the DNA is focused on bringing them to lay more eggs per year.”

The culling of male chicks is an industry-wide problem, and several sexing solutions have already been developed to prevent it, in addition to the gene modification created by Huminn Poultry.

One solution is to look inside the egg while the chick is still developing.

The technologies involved in this process include an MRI, which uses a magnetic field and radio waves to take pictures inside of the egg, and extracting liquid from the egg and analyzing it to determine the sex.

But Mor explains that farmers can only make out the sex of the chick on day 13 of an egg’s incubation – and by the time its sex can be determined, the assumption is that it can already feel pain.

“Even if [these technologies] can identify that there is a male in the egg, they still need to get rid of it,” says Mor. “This would cause the little creature inside to suffer.”

Other methods include the one devised by Israeli startup Soos, which uses soundwaves while the chicks are incubating to increase the likelihood of ovary development among male chicks by 50 to 80 percent.

Even so, Mor says that the Huminn Poultry gene is the most viable and accurate solution to the culling of male baby chicks.

The technology was developed by Dr. Yuval Cinnamon, embryology specialist at the Volcani Institute, Israel’s national agricultural research center.

“He thought that the best solution was to prevent the male chicks from ever being developed,” says Mor.

Huminn Poultry, based in Rehovot, says it will take several years to fully integrate its gene into an entire breed of chickens.

Nonetheless, he believes that the solution will be integrated by at least one breeding company within the next few years.

“We don’t require any sophisticated systems or technicians to alter the equipment of [egg producers],” says Mor.

“The beauty of the solution is that once it’s done, it’s done,” he says. “It won’t need to be integrated again into the same chicken breed.”

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Facebook comments