Driverless cars are the future. But for the ordinary motorist, that future is still a way off.

The AI that drives autonomous vehicles is clever, but not clever enough. Yet.

It struggles with what engineers call “corner cases” – the unexpected and unpredictable set of circumstances that currently call for human, rather than artificial intelligence.

So if someone places a traffic one on the car’s hood, the AI will freeze. If high winds bring down a branch, a sink hole opens up in the road and a runaway shopping cart hits the car during a freak sandstorm, AI will be stumped.

We’d use our common sense and life experience to deal with these challenges. AI doesn’t have any.

That’s where Ottopia, a Tel Aviv-based startup, comes in. It provides human assistance to vehicles that are already operating on public roads, and elsewhere, without a driver.

At the moment we’re mostly talking about the robotaxis that are ferrying passengers around a small number of cities in the US, but in the next few years it will also include trucks operating on pre-defined routes.

It’s all about “controlling the environment,” says Paul Kandel, the company’s Director of Business Development.

The more variables there are, the more challenging it is for AI to cope.

By reducing those variables, some cities in the US, China and elsewhere are able to allow driverless vehicles on their roads. They’re classified in jargon of the driverless industry as Level Four, which is one step from total autonomy.

They may be restricted to certain roads or certain times of the day, to keep those variables to a manageable minimum.

The vehicles don’t need a full-time driver, but they may need their hand holding if the going gets tough.

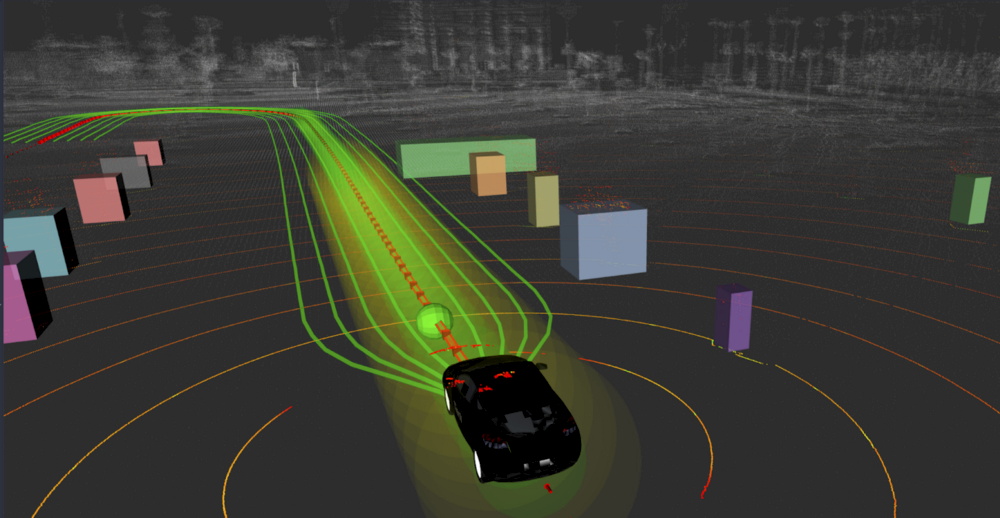

Ottopia does that hand-holding – or “teleoperations” – with sophisticated software and a robust, patented technology that guarantees near-uninterrupted contact between vehicle and command center. The last thing you need in a driverless emergency is a patchy Wi-Fi signal.

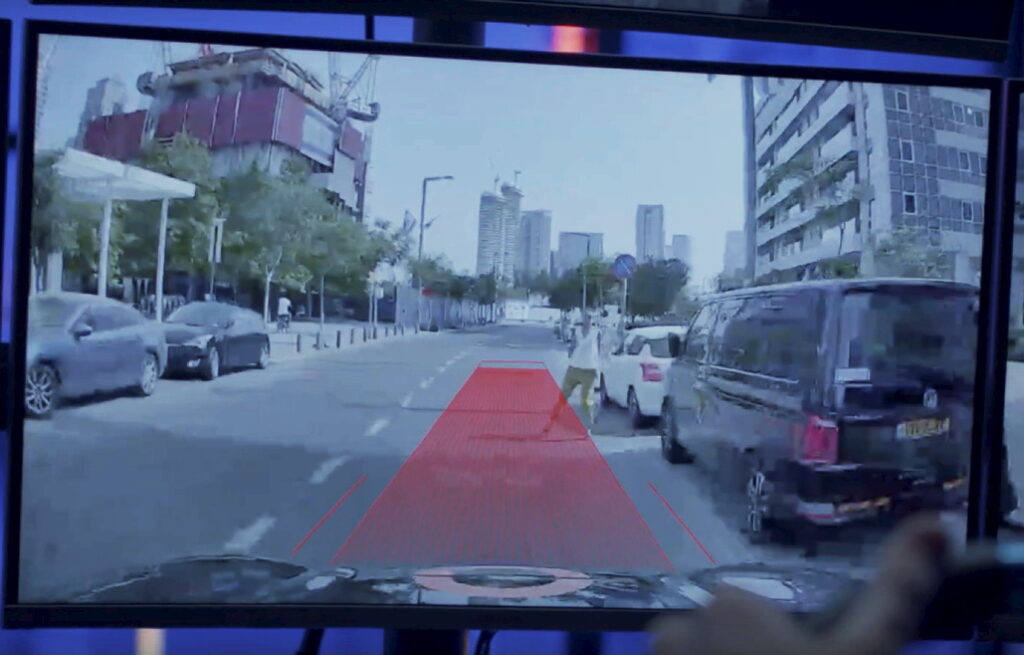

“The simplest level of teleoperation is where the remote operator is monitoring a vehicle,” says Kandel.

“The second level is remote assistance, where the vehicle might say, for example, I’m not sure what to do in this scenario, because I came across a new construction site that’s not on my map, or there’s a there’s a car blocking my lane. And the third level is actual remote driving.”

That’s basically when an operator in the command center grabs the steering wheel, puts their foot on the pedal and takes full control.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

Ottopia says the technology breakthrough that sets it apart from other companies in teleoperations is its ability to maintain contact with the vehicles it’s controlling.

“There are some other good companies out there,” says Kendal. “But when we’ve gone through the evaluations with customers and potential customers, I’d say we are pretty consistently in the lead in terms of the lowest latency, highest reliability and best cybersecurity architecture.”

Ottopia has a number of patents around what’s called network bonding, which means using any available data to “bond” into one data stream.

“Our technology has a bunch of layers of redundancies and fallbacks built in,” says Kendal. “So in a worst case, if you completely lose a connection, you will still have collision avoidance and safety critical systems on the vehicle.

“Our software squeezes a lemon out of everything that network has to offer, to get the best performance possible.”

BMW chose Ottopia as the “preferred multi SIM teleoperation technology” to support its autonomous driving services.

The startup also provides the teleoperations for US company Motional, which launched robotaxis last year in Las Vegas in collaboration with cab services Uber and Lyft. For the time being, they only operate on weekdays during daylight hours and on restricted routes. Passengers don’t pay during the current trial period.

If the vehicle encounters a problem it can’t deal with, a teleoperator will either offer guidance or take over.

Ottopia also provides remote driving and assistance software to US company Magna for its “last mile” delivery robots, which started delivering pizzas in Detroit, USA last March. Their vehicles fitted with the Ottopia platform drive on public roads at up to 20mph.

And last month Ottopia announced a partnership with San Francisco-based Serve Robotics to develop its autonomous sidewalk delivery robots.

Ottopia’s software also works with autonomous vehicles in industrial settings, such as forklifts, trucks, yard trucks and construction machines, where the environment can be controlled.

But drivers like you and me must wait for the technology to develop – best guess is a decade – and for the prices to become realistic, before we can fully embrace it.

“The industry as a whole is realizing that for consumer vehicles that you and I own it’s going to take a long time for our autonomy to really be there,” says Kendal.

But there may still be benefits in the near future. “I think that in the meantime, there’s a lot that we can do with our customers to bring the value of a driverless experience,” he says.

That means a remote human driver could take over the controls, drop you off at a restaurant, find a parking space, and collect you later, after you’ve enjoyed your meal – and a couple of glasses of wine.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments