Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, is helping thousands of pupils pass their geometry tests.

Six hundred schools in Israel are currently using Origametria – a series of fun, hands-on lessons that covers the entire curriculum.

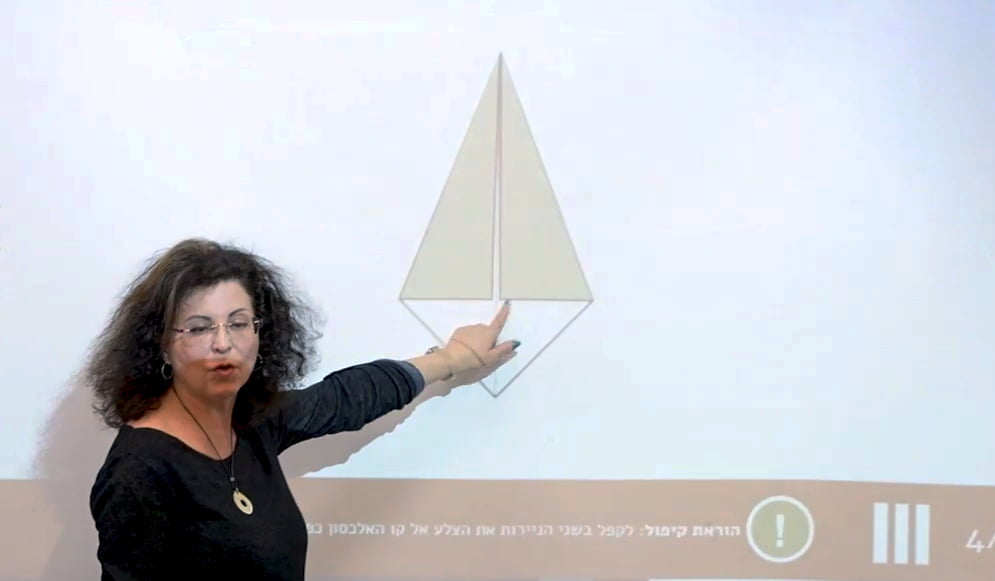

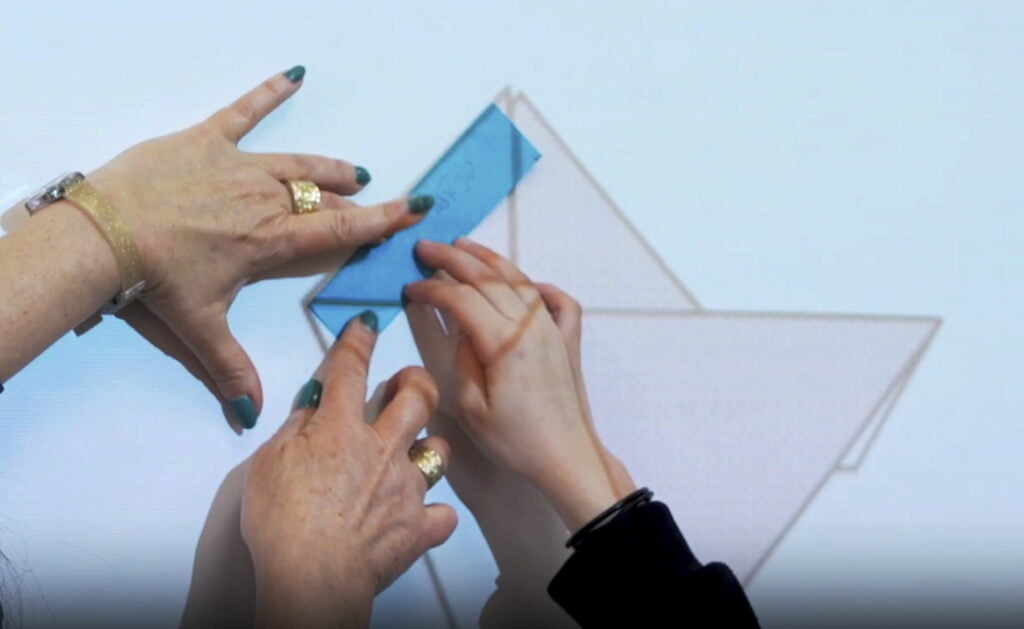

Youngsters watch animated videos on screen, follow the folding instructions – as they unfold – and learn about polygons, symmetry, quadrilaterals, trapezoids and more. Often without even realizing it’s a lesson.

Miri Golan and Paul Jackson, who founded Origametria, met and fell in love in 2000 through their shared passion for origami, and decided it would be the perfect way to teach geometry.

Not as one-off novelty, but as the default method for youngsters of all ages, from kindergarten to seventh grade (age 13) to learn everything they need to know about the size, position, angles and dimensions of shapes.

Miri, a special education teacher from Herzilya, Israel, founded the Israeli Origami Center in 1992.

Paul, originally from England, has an MA in fine art and is the first professional origami artist outside Japan, and has written 40 books on the subject.

They teamed up with Dr Johnny Oberman, a mathematician who was involved in drawing up the curriculum for teaching math in Israel’s schools.

Together the three of them developed a complete geometry program that keeps kids engaged and interested in a subject otherwise regarded by many as dry and dull.

“We realized that origami was perfectly suited to teaching geometry,” says Miri. “It’s a problematic topic to teach and for the pupils it’s a difficult topic to learn.

“We built it as an online program and all the business advisors said we were making a mistake. But we proved them wrong. Before Covid we had 100 schools in Israel, now we have 600.”

The learning program they’ve developed was independently tested on 88 second-graders (age eight), at both Hebrew- and Arabic-speaking schools in Israel where pupils performed poorly in geometry.

After 23 sessions throughout a school year, their test results were up from an average of 45 percent to 75 percent.

The report’s authors concluded that Origametria had “eliminated the initial knowledge gap between pupils of different socioeconomic levels, sectors, genders and levels of achievement.”

It was, they concluded, “highly recommended for the use of all pupils and educators.”

The program is approved by Israel’s education ministry and has been used so far to teach 150,000 pupils.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“The children make a model elephant, they learn about polygons and they have an amazing lesson,” says Miri. “We cover the whole curriculum, and the geometry curriculum around the world is the same.”

The class teacher doesn’t need to study origami, because an animated video provides step-by-step instructions and poses questions for pupils with every fold.

“The kids don’t want to make a pyramid or a cube all the time, you know, geometry, they want to make something fun and cool,” says Paul.

“They learn by making, not by looking. The problem with geometry was always that people would learn it from books, and that doesn’t work.

“As everybody knows, you learn best when you’re making something rather than just reading a book, or clicking and swiping on a monitor.

“It reaches the children who were usually not very interested in maths and geometry. Children with ADHD or children who are dyslexic are often the star of the Origametria class.”

Each class gets 1,000 sheets of brightly-colored origami paper, some of it squared so pupils can measure and cut out particular designs as part of the lesson.

There are a total of 200 lessons, from basic – such as folding the paper into a ruler and using it to measure a polygon so a child can determine what the shape is – to more advanced concepts.

“Quite a lot of maths teachers know a little bit of origami,” says Paul. “And perhaps one or two lessons a year, they’ll teach children how to make a pyramid or whatever.

“But what we have done is to build a curriculum, not just a few fun lessons. And we’ve also understood how to integrate this into the education system.

“It’s animated, with questions on the screen for the children to investigate, so the teacher doesn’t need to know origami. But she does know that the geometry is being taught properly.”

Miri is adamant that lessons with Origami are not simply “enrichment” – an add-on to standard lessons. They are the standard lessons.

And she’s keen for children to start the Origametria program at the earliest possible age.

“When I brought origami to Israel, school principals laughed and said it was for the local community center, not for the classroom. We now feel we’re ready to take it to other countries,” says Miri.

Origametria has in fact recently signed a contract with the education ministry in Azerbaijan, the former Soviet republic, and is in talks with Pittsburgh and other US cities. The program is currently available in English, Hebrew and Arabic.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments