Technology that analyzes sewage for disease is being used to help Israel’s off-grid Bedouin communities.

As many as 150,000 Bedouin – semi-nomadic desert dwellers – live with inadequate sewage systems in the southern city of Rahat and in many smaller towns and villages across the Negev.

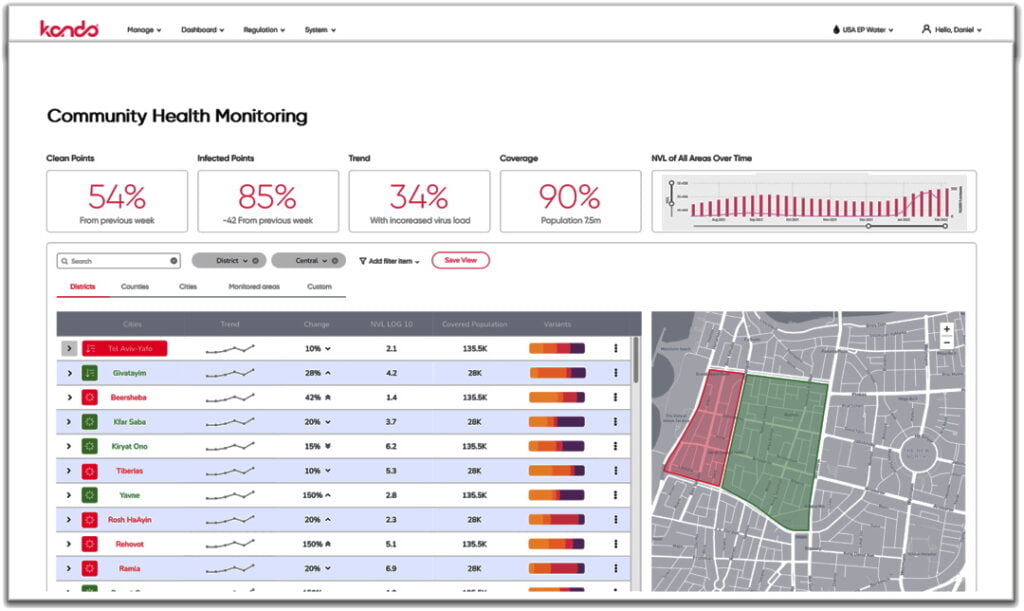

Portable smart samplers developed by the startup Kando, based in Tsur Yigal, central Israel, are now being used to test their wastewater to provide early warnings for outbreaks of anything from diarrhea and dysentery to polio, flu, norovirus and Covid. The self-contained units are lowered into manholes to take their measurements.

That information can be quickly passed on to health authorities, to implement vaccination programs, enforce lockdowns in the case of Covid, or take other appropriate action.

Sewage samples are a remarkably good indicator of illness. It can take seven to 10 days for an infected person to show symptoms and realize they’re ill. But all that time the viral load from their body is being excreted into the sewer and can be detected by the sampling units.

The same technology can, incidentally, also measure levels of nicotine, artificial sweeteners and other indicators of people’s overall health.

Testing sewage for pathogens – disease-carrying organisms – is well-established, but has always been done on a large scale at water treatment plants that cater for hundreds of thousands of people.

Kando is able to pinpoint much more localized outbreaks, because it samples the wastewater much closer to its source.

It identifies the best locations to install small automated units, and they take regular samples throughout the day for analysis at a lab.

It takes just 48 hours to provide targeted analysis of infected areas, identifying low, medium and high risk areas.

“We’re able to collect this data and communicate it back to decision makers,” says Hila Korach Rechtman, Kando’s Head of Research.

“The laboratory analysis is basically something that everyone can do. But analyzing the locations to sample, and then translating this data into actionable insights that can be implemented by officials or health officials is the holy grail.

“From then it’s their decision. We can’t really affect what they’re doing with the data, but the real innovation is translating it into something that they can use.”

She says Israel has been monitoring pathogens in wastewater since the late 1980s, but the ability to take measurements locally makes a huge difference.

“If you monitor water in the neighborhoods, you basically can get a better understanding of how the disease is behaving and how it’s transmitted,” she says.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeFew of us had even heard of wastewater intelligence – or sampling sewage for disease – before the Covid pandemic. But here in Israel at least it became well known as a method for assessing overall levels of infection.

Kando’s technology was first deployed across Israel as a Covid measure in April 2020. Israel’s Ministry of Health introduced twice-weekly testing of all towns with a population over 20,000 to monitor the spread of the pandemic.

That same system is now being used to help the Bedouin communities in the Negev, southern Israel, that have some kind of sewage infrastructure, and adaptations are being to introduced to do likewise for those that have nothing more sophisticated than a cesspit.

In many places there is no sewer network and the Bedouin use unsanitary cesspits to discharge their sewage, says Dr. Clive Lipchin, Director of the Center for Transboundary Water Management at the Arava Institute, an environmental and academic institution.

“This is a great concern, not just to the Bedouin, because of their exposure to waterborne disease from untreated sewage,” he says. “But the bigger question, and one that concerns the Israeli government, is if the sewage that has not been treated eventually gets to the water table. And that’s a source of water that we all are dependent on for drinking.

“So our intervention is to try to see how can we try to resolve some of these issues.”

He says vital infrastructure such as water, wastewater, and sewage, is basic at best in some places, and non-existent in “unrecognized communities”, which are, he says, considered illegal by the government.

“The level of morbidity in the veteran population, specifically with women and children, is much higher than the general Israeli population.

“We’re trying as an NGO, as civil society, to try to remediate some of these issues. And we’re very pleased to have an opportunity to collaborate with Kando as a leading Israeli water technology company, that really gives us some of the tools to try to assess some of these things.”

The Bedouin are, he says, a very conservative society and very wary of states agencies and intervention. Their vaccinations level during the Covid pandemic were the lowest in Israel.

“The government was completely at a loss of what to do,” says Dr. Lipchin. “We went in, and we sampled the wastewater to give an indication of the spread of the pandemic.

“When we compared the Ministry of Health data to ours we saw a huge discrepancy. Our data was showing much higher rates of infection than what the government actually was looking at.”

The project was conducted with scientific support from the laboratories of Prof. Ariel Kushmaro and Prof. Jacob Moran-Gilad of Ben-Gurion University.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments