Capsules of sterile males will wipe out populations of nuisance insects

The world’s deadliest creature isn’t a snake, a shark, or even a human. It’s a mosquito.

They kill over a million people a year, mostly from malaria, and infect more than 700 million with diseases – almost one in ten people.

There’s a solution being developed in Israel that isn’t another chemical or repellant filled with pesticides. It’s a capsule filled with the larva of sterilized male mosquitoes that arrives through the post.

“Think about a Nespresso machine,” says Vic Levitin, Co-founder and CEO of Jerusalem-based Diptera.ai.

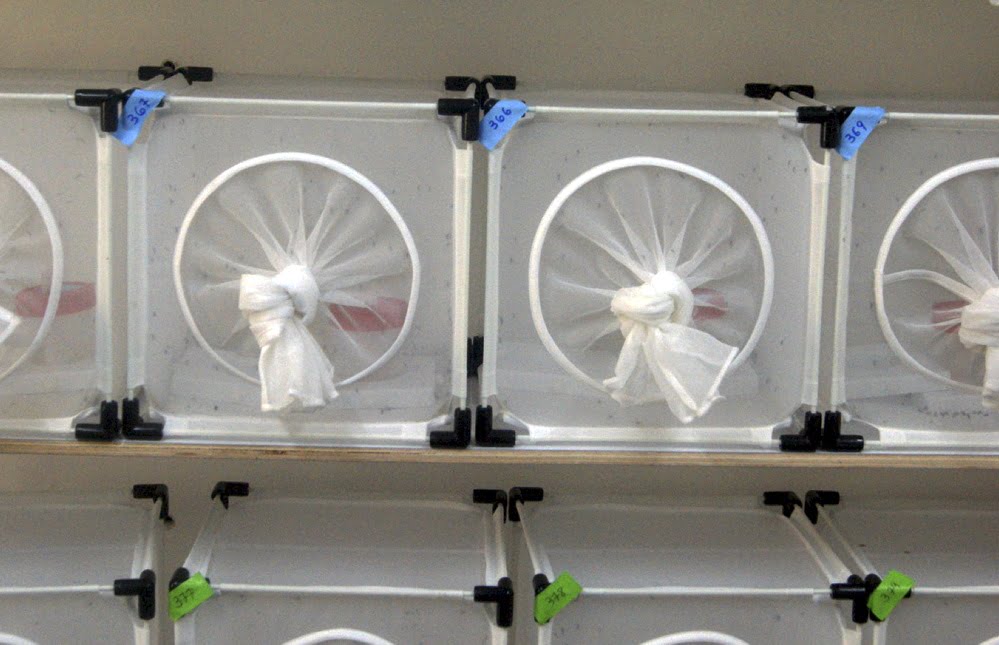

“You will have a release box placed in your backyard or garden, and you will receive weekly shipments of capsules containing sterile males that you place into the release box, and the machine will continuously release them throughout the week.”

It’s only the females that bite humans. And they only mate once in their short six-week life. The Dipteria.ai solution ensures they mate with males that have been sterilized.

That means they cannot lay fertilized eggs, causing the population to die down – by as much as 90 per cent in some trials.

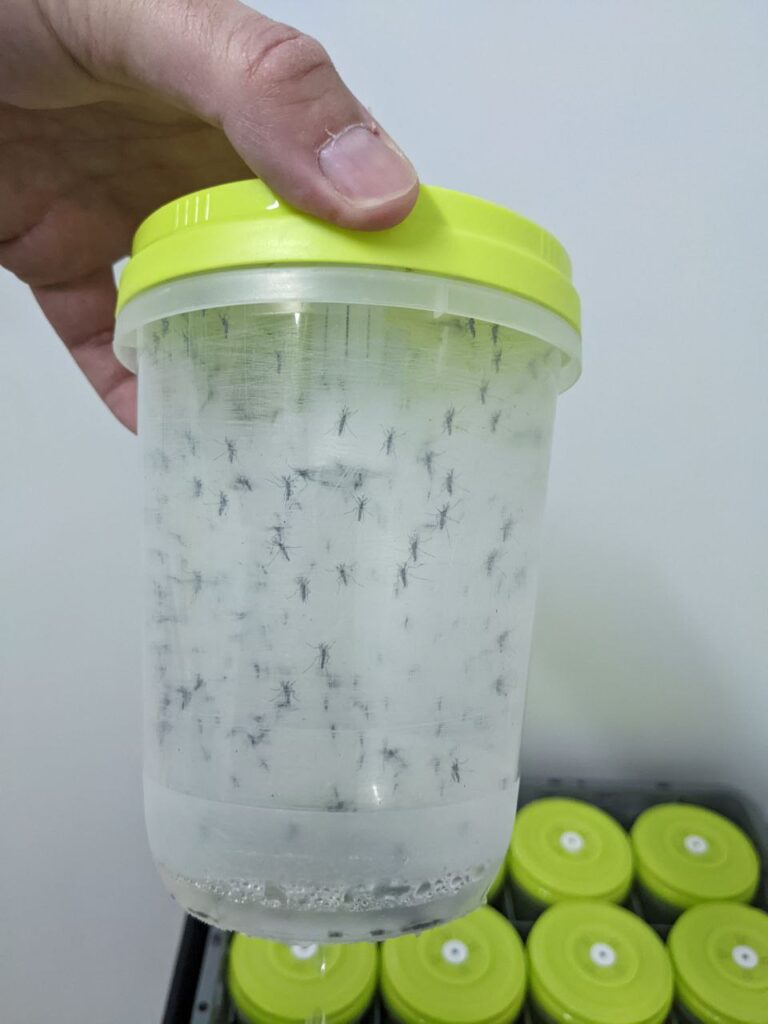

Home owners will, during the mosquito season, sign up to receive weekly deliveries of sterilized males in capsules the size of a 500ml bottle.

The capsules fit into a release box, about the size of a shoebox. The males emerge, feed on nectar from flowers, spend a week happily mating… but produce no offspring.

The Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) is not a new method, and was first applied on a significant scale in the 1950s against the screw-worm fly, a parasitic fly whose maggots feed on the living tissue of mammals.

Adult males live for just seven days on average and spend their entire lives mating. Possible delays mean packing and shipping them to consumers wouldn’t be practical.

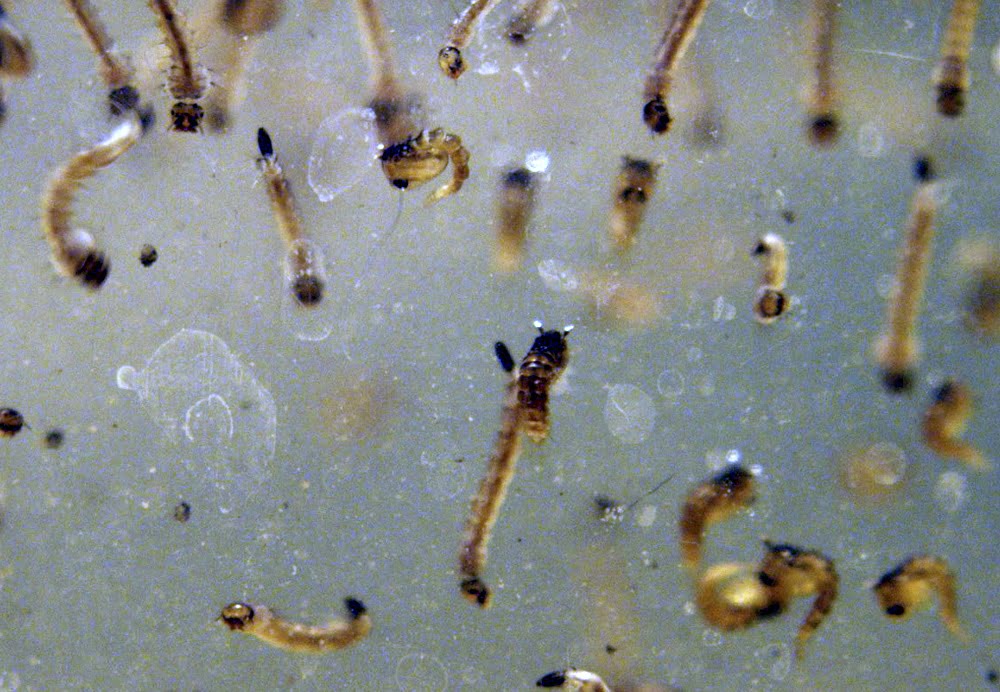

But Diptera.ai has found a way of effectively sex-sorting mosquitoes at the larva stage, before they reach adulthood.

“We built a platform that allows sex-sorting mosquitoes and other insects using computer vision at the larval stage,” Levitin tells NoCamels.

“With computer imaging, we can look inside the larva and understand if it’s going to become a male or a female, even before the sex is actually determined.”

It’s easy to sex-sort mosquitoes at adulthood. Females are larger, and have unique mouthparts (proboscises) that are built to pierce human skin.

But it’s impossible to tell the difference between males and females when they are at the larval stage.

“And essentially what we do is we unlock the main bottleneck, because other companies can sort mosquitoes and other insects at the adult stage,” he says. “We do this at the larval stage.”

“You can take the most advanced microscope in the world, look inside the larva, and still not be able to see the differences.”

Levitin says his company can detect these differences with a “specific optical set”, which includes particular lighting and other conditions.

Once Diptera.ai sexes the mosquitoes, they sterilize them at the pupae stage with X-ray radiation similar to a microwave oven, and pack them into capsules.

“We can have one central production facility, from where we can ship mosquitoes across a country or even a region of countries. So one facility can cover all of the US, or all of Europe.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeDiptera.ai expects its capsules and release boxes to be commercially available in the US by 2023, and has just completed its first-ever pilot in Kibbutz Tzora, near Jerusalem.

In the beginning of the mosquito season, which is around March in Israel, Levitin and his team released around 300,000 mosquitoes every week in the kibbutz.

“We were slowly driving through the kibbutz in these golf carts, and just releasing the mosquitoes,” he says.

The team monitored the mosquito population through the use of tens of mosquito traps. They placed traps in the nearby Kibbutz Nahshon, which served as the control for the pilot.

Diptera.ai’s solution showed about a 90 per cent suppression of the mosquito population in Tsora versus the control center.

Existing synthetic mosquito repellents are not a sustainable solution to countering these pests.

Evidence in recent years shows that pyrethroid, a common insecticide, can reduce sperm count in men and produce reproductive toxicity, as well as being a possible carcinogen. And DEET, the most widely used synthetic insecticide, is slightly toxic to birds, fish, and aquatic invertebrates.

“It’s also been shown in multiple scientific studies that mosquitoes are quickly becoming resistant to the pesticides because they have such fast evolution, which causes them to adapt to these insecticides,” says Levitin. “This means that every season, we have to use more and more toxic pesticides.”

A 2018 article found that mosquitoes adapt to insecticide exposure at the molecular, physiological, and behavioral levels – to the point where females learn to avoid pesticides after a single non-fatal exposure.

SIT methods don’t wreak havoc on our bodies or on the environment, and they aren’t something mosquitoes can adapt to.

“Moreover, the mosquitoes we’re targeting, namely the Asian tiger mosquito, is an invasive species in California, in Israel, and in Europe. If anything, we’re helping the local ecosystem recover,” says Levitin.

As for expanding to parts of the world where malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases are common, he said: “We’ve learned very quickly that if we want to make a real impact in Africa, we have to build a strong, self-sustained company in the western world.”

Before founding Diptera.ai, Levitin had developed two software companies – but his outlook on life changed when he became a father for the first time.

He wanted to do something with more meaning and finally met with his two co-founders, doctors at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel, who developed the initial technology.

Diptera.ai isn’t the only company trying to use SIT to decrease the mosquito population and prevent unnecessary deaths.

Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc., is also trying to commercialize SIT. The Debug Project releases sterile adult male mosquitoes too, but has not determined how to sex-sort them from the larval stage.

“It’s kind of funny to call anybody a competitor because there’s no commercial offering right now,” says Levitin.

“We also learn a lot from each other. Google’s done a pilot of this technology in 2018, and a lot of the work we’re doing in Tsora is based on their findings from their pilot in Fresno, California.”

As for the future, Diptera.ai aims to decrease the cost of its technology, scale up its production, and commercialize its product. It estimates that subscriptions will start being available in the US by 2023.

And in Israel, Diptera.ai is talking to municipalities to find ways to implement their solution across Israeli cities. It eventually wants to develop its technology to tackle agricultural pests.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments