The ongoing COVID-19 health crisis had resulted in a shift to a more digital way of life, as there is still some hesitance to head back to regular activities. More movies are being streamed at home. Restaurants that were once sit-in only now offer take out options. More people are spending free time gaming. The number of online shoppers has skyrocketed.

More time spent online gaming, shopping, TV binging, and browsing social media means an expanded digital footprint. And, in turn, that means growing concern for data privacy and security.

“There is always a chance your data will be used against you,” Gal Ringel, CEO and co-founder of Israeli startup Mine, tells NoCamels in a phone interview as he refers to past data breaches including the most recent cyber attack on low-cost airline Easy Jet last month. The attack accessed email addresses and travel details of some nine million customers and credit card details of more than 2,000 customers.

But, Ringel adds, the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) which became enforceable in May 2018, has “defined for the first time in history that our own personal data is also our own asset.”

While the GDPR has been effective in both establishing the definition of personal data and giving control of it back to its owner, often the user is not even aware a company has collected his or her personal data.

Israeli startup Mine, an AI-based platform that assists users in reclaiming their personal data, empowers the user to discover his or her digital footprint while also supporting them in their efforts to take it back.

The company was co-founded by Gal Ringel, Gal Golan (current Chief Technology Officer,) and Kobi Nissan (current Chief Product Officer). Ringel and Golan have held leadership roles in the elite IDF Cyber Intelligence Unit 8200, while Nissan has a background in the consumer gaming industry. All three have worked in companies such as Nielsen, Verizon, Microsoft, Accenture, among others.

The company emerged from stealth mode in January with a $3 million seed round backed by global investment firm Battery Ventures and Israeli VC firm Saban Ventures. It has had an encouraging few months despite the pandemic as more people went online and became more aware of their digital footprint.

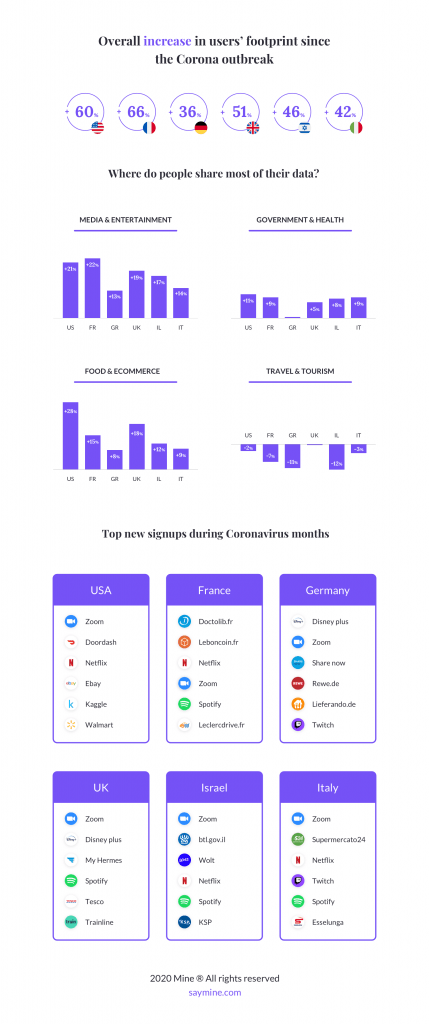

“We discovered that the corona[virus] actually increased data exposure by 55 percent, which is massive,” Ringel says, noting that the figures were measured between March (around the time the virus hit Italy) and May. The insights collected were based on the company’s 35,000 registered users in six countries: Israel, France, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the US.

According to Mine’s coronavirus findings, the video conferencing tool

Zoom was the most popular new service that people signed up for across all six countries. Netflix took third and fourth spots in all countries, except Germany and the UK, where users favored Disney+.

Digital music service Spotify was popular in four of the six countries. Online grocery sites like Walmart in the US and Tesco in the UK, were popular, too. In Israel, the second most popular site after Zoom was the Bituach Leumi (National Insurance) website, which Ringel said accounted for the sharp number of unemployed in the country who were using online services to receive their unemployment benefits.

“The bottom line is that COVID-19 actually got us to share more of our personal, sensitive, financial, and health information than before, which is why a service like Mine got even more popular during this time,” says Ringel, “A lot of people wanted to know what companies have collected their data during that time, what services they signed up to, where they purchased things.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeRight to be forgotten and privacy policies

Mine has analyzed some four million digital services, Ringel tells NoCamels, informing its customers which online sites and services hold their data. Some of the services that store the data are ones that the user probably doesn’t even remember, he says, having used them once. Many of the discovered sites are not used on a daily basis.

The average user has 350 companies as part of their digital footprint, according to the company’s findings. (Prior to the arrival of coronavirus in Israel, this reporter visited Mine and learned her personal data was being stored by just over 200 providers. This month, after Israel’s strict lockdown, that number has skyrocketed to 607 companies.)

Mine gives users ownership over their own data by leveraging global privacy regulations, specifically the GDPR’s “right to be forgotten” clause’. This allows users to request that online services delete their data. Mine can also send a reclaim request to each company on behalf of the user.

Mine works on two avenues simultaneously. First, it developed an AI system to analyze a given company’s privacy policy to learn what data it collects on users. Second, the Tel Aviv-based company uses non-intrusive machine learning and NLP (natural language processing) algorithms to monitor a user’s email inbox to find companies that store their data.

For example, if a user signs up to Airbnb, they will get a welcome email and Mine’s system will know that that specific interaction was a signup. Since the company has analyzed Airbnb’s privacy policy, it knows that if a user signed up for Airbnb, they had to give them a first name, last name, date of birth, and a copy of their passport. Mine knows what data you are handing over, based on the interaction, but it doesn’t know the content (i.e., the passport number) and it doesn’t need to.

“This is how we know what data you’re giving to companies, without knowing what that actual data is,” Ringel explains to NoCamels. “We never read the content of your emails because we don’t want to see your sensitive data. “We only process your email subjects and meta data. Moreover, we don’t keep any trace of your emails in our database. The only data we keep about you as a user is your email address, which you signed up with, full name (to send privacy requests to the companies with your name), and the list of companies we discovered in your footprint,” he explained.

After this process, Mine then lists the companies on their own dashboard, categorizing them by financial, identity, online behavior, and social network data.

If the user wants to “reclaim” or remove their data from an online service, the user needs to file an official data subject request. Companies must validate the user’s identity, to make sure they’re not deleting someone else’s data by mistake. If a user allows Mine to send emails on his or her behalf, an email with the deletion request will be automatically sent from the user’s inbox to the relevant company. The company says this increases the efficiency and success rate of reclaim requests and decreases the chance that companies will ask for further identification.

The company says it has sent more than 300,000 “right to be forgotten” requests so far.

“What we see now in the data as the coronavirus numbers start to decrease is that a lot of people are starting to delete all the services that they are not using anymore, that they used during the lockdown. So they use Mine to delete them,” Ringel tells NoCamels.

Ringel stated that because most people are currently not traveling, the company recently ran a campaign urging users to clean up all the travel-related services accumulated over the years. Examples of services include tellers, flight cache, WiFi services at the airport, car rental, and anything related to the recent trip.

Amid a global push for new data privacy standards, and with a public empowered to take back data ownership, control their own digital footprint, and remove private information from internet searches, Mine is adamant that their users know that they take privacy policies very seriously.

Mine is a free service, with a paid version coming out in the future. The paid service will handle all of the reclaiming data follow-ups for the user, while the free service requires the user to do it himself.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments