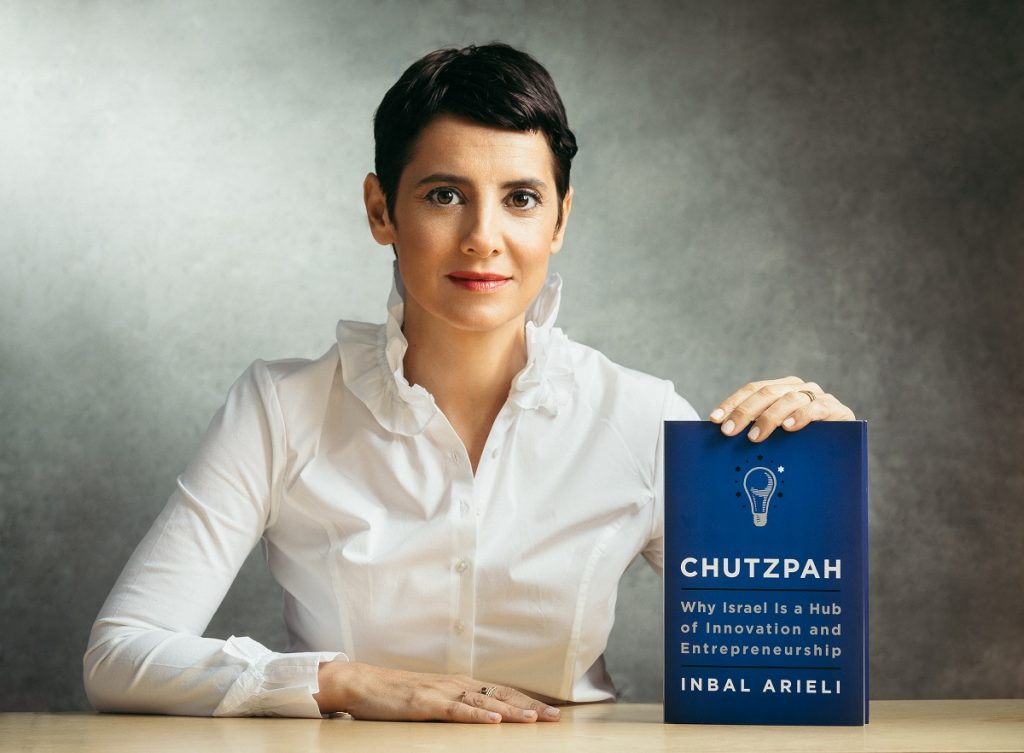

What’s the secret to Israel’s unique successes as a world-renown center of innovation? It all starts in the playground, says Inbal Arieli, an Israeli serial entrepreneur, one of the country’s leading women in tech and – most recently – the author of “Chutzpah: Why Israel Is a Hub of Innovation and Entrepreneurship.“

Playgrounds in Israel can be quite distinctive, after all. There’s usually a lot of yelling, running, creative climbing techniques, rough play, power struggles, kids crashing into each other, some sharp objects, and somewhere nearby, a small child is urinating openly. In other words, it’s a “balagan” – a mess.

SEE ALSO: Top Researchers, Cultural Sensations And Star Athletes: The Most Influential Israelis Of 2019

Arieli’s 2019 book unpacks Israeli culture and its approach to parenting and raising children in an environment of uncertainty and messiness that encourages creative thinking, problem-solving, risk-taking, pushing boundaries, overcoming failure, and even challenging authority. With this disruption-focused mindset, Israel has become the “startup nation” and Israelis have been raising generations of entrepreneurs who are changing the world, she argues in the book.

Arieli says that this approach to child-rearing is not a set strategy and that “Chutzpah” is by no means a parenting book.

“It’s a business book,” she tells NoCamels in an interview in south Tel Aviv where Arieli, co-CEO of assessment and development company Synthesis, maintains an office. “The book is for entrepreneurs, for executives, for entrepreneurs-to-be, and for anyone who wants to start a business or lead a business. That’s where I’m an expert.”

“But when I see Israeli entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs from all over the world, I recognize a lot of elements that are very similar to the way Israelis were brought up. And that’s where this idea started,” she says.

Arieli has had an illustrious career spanning over two decades, beginning with her military service in the elite IDF unit 8200. She then pursued a number of academic degrees while immersing herself in the Israeli tech ecosystem, taking up executive roles and founding innovation programs and accelerators.

Arieli co-founded Synthesis in 2017 and the company now provides professional assessment services to over five dozen clients – mainly companies – across North America, based on methodologies developed by military psychologists here in Israel, she explains.

Her latest project, “Chutzpah,” has been years in the making and is based on her popular lecture “The seeds of Israeli entrepreneurship,” first delivered in 2013. The book was first published in English by Harper Business and has been translated to Hebrew with future translations expected in Korean, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Taiwanese.

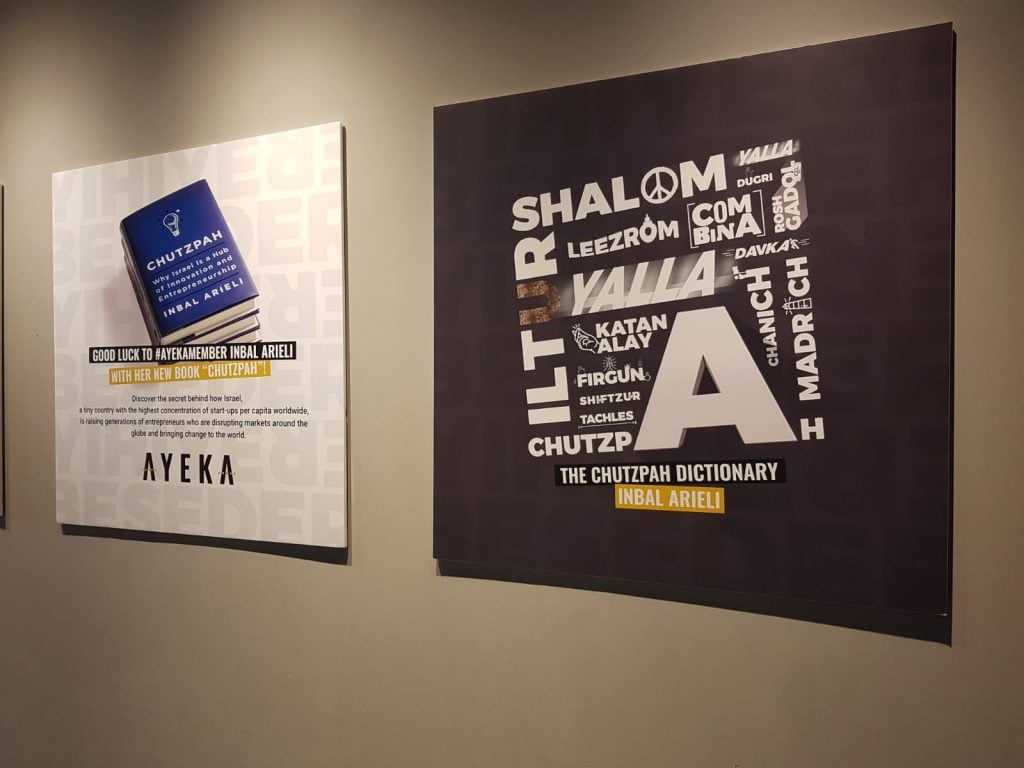

Arieli’s website, the Chutzpah Center, offers interesting glimpses into the book including reviews, poignant quotes from Israeli entrepreneurs and business leaders featured in it, and even a “Chutzpah dictionary” highlighting Hebrew words commonly used in Israel. These include “tachles” (loosely translated as “bottom line” or “literally” depending on context, “rosh gadol” (literally “big head” but it means someone who thinks creatively and thoroughly), “leezrom” (to go with the flow and embrace the unexpected), and – her favorite – “firgun” (to be genuinely happy for someone else’s achievements and successes).

Arieli is now engaged in a series of book tours encouraging people to “own their chutzpah” and says the book has been resonating with many.

“From what I’ve seen over the past few months since the book has been released, it makes people think, people have an emotional reaction to it. It makes them ask questions; they go through a thinking process, a questioning process, a confirmation process. The book remains with them after they finish reading it,” she explains.

Here is our full interview with Arieli where she talks about how Israeli chutzpah has helped this nation become a force of entrepreneurship on the world stage. Her answers have been edited for length and clarity.

NoCamels: Can we start with you giving us your definition of chutzpah? Because it can be many different things like audacity, boldness, cheek. How do you define it?

Inbal Arieli: I think of it as a combination of things, it’s not just one thing. Chutzpah is a complex concept and it encapsulates a lot of different elements. The definition that resonated with me the most is actually the one that I quote in the book by [Chinese tech magnate] Jack Ma who said chutzpah is “dare to challenge” because it combines bravery and action. It’s action into the unknown, it’s new territory, it’s a challenge, and with this tailwind of energy. That is what chutzpah is for me.

It could be bad, it could be good, the direction it could take could vary. But chutzpah itself is this boost of energy toward action. It’s not fearlessness, it’s a way of being where you are willing to cope with fear.

NC: And Israelis cope. It’s a society that copes with fears and hardships and challenges.

IA: Israelis have no other choice but to cope. We often don’t have the luxury of just pausing and processing and strategizing. There’s no time, there are no resources, there’s always something happening. And in that environment, yes, you just cope.

People here are very involved and they’re very passionate and I think that’s a good thing. They’re involved in their neighborhood activities and in their communities, and in their country politics, and they have an opinion about everything. And it’s because they care, because they’re very emotionally invested. So that gives you perspective in life.

NC: Is Chutzpah an Israeli trait? A Jewish trait? Did Israelis “perfect” it?

IA: I think it’s a human trait that is well-practiced here. Let’s take, for example, kids. They naturally have more chutzpah than adults. Anywhere in the world. Kids possess that. It’s part of who they are. We don’t call it chutzpah but the characteristics are there. They’re honest and forward, they’re in the process of doing, they’re playing, they’re not thinking too much, they’re acting intuitively.

For me, that’s proof that this mindset is a human mindset. Certain environments encourage it more. Certain environments practice it more and train more. Like in Israel.

And some just block it or neglect it.

NC: Do Israeli parents just consciously nurture it more? What’s their process?

IA: There is no strategy behind it. It’s part of the general mindset. I can analyze it from so many different aspects.

You could say, very practically for example, that to maintain a reasonable Israeli household today you need two incomes so both parents have to go out and work. That requires kids to be by themselves a lot, to be very independent. The way the education system is organized here; school ends at say 1:30 pm or 2:00 pm, so something needs to happen then.

You could say the weather is also a factor. It’s usually warm here so that encourages people to spend a lot of time outside and kids do spend a lot of time outside in Israel.

The fact that Israel is a safe country in terms of crime. It’s a really safe country, so that’s another factor.

The fact that we are not litigious, we don’t have this liability approach where everything we see is translated into a lawsuit.

So we appear to take more risks. There are just so many reasons but none of them is strategy. It’s not a systemized parenting ideology.

And this is why the book is so interesting to so many Israelis. Because it actually tells their story, their daily story. Nothing in the book is new to Israelis, but in fact, everything is new because it’s providing fresh observations on an existing landscape.

NC: In addition to the feedback you receive from Israeli readers who feel seen and recognized, what have been some of the reactions from non-Israelis?

The book’s main audience is in the US. I definitely didn’t plan for the book to come out so quickly in Hebrew and for it to be so well accepted. Because other books in this category were not well received. Their Hebrew versions, at least, because it felt like an analysis of things we already know about ourselves.

And it appears the fresh perspective and the way I presented it enabled readers to actually really connect with it in Israel.

In the US, my main target audience is in the business world ranging from business school students to heads of board of directors and general partners in investment funds. And they each see different things in the book. I think what’s common to all of them is the fact that, yes, it’s a book that tells the story of Israeli childhoods, but for them, it’s a book about skills. It’s about soft skills that are so difficult to be practiced and taught. And how with practice and awareness, anyone anywhere in the world can develop these “chutzpah” muscles within themselves.

A student may pick up different things in the book than a C-level executive, given their different experiences, their maturity, and their careers, but what’s common is they all understand these mindsets that the book presents. These mindsets of soft skills, which in my opinion are the most critical for the future of everyone on this planet. These readers understand that these are actually things they can practice.

For my audience in Jewish communities, for example, the book provides for them a better understanding of Israel. So things they’ve noticed when they come here on vacation or meet Israelis abroad, they suddenly understand certain things. And it’s not just even understanding, they start to think ‘oh maybe it’s not so bad.’ [laughs]

I’ve also done talks for high school students and they immediately want to talk about how they can implement these things and improve themselves. And I’ve also spoken to communities of elderly people and for them, it’s a kind of comparison to what their childhoods were like.

And it’s not just North America. I have received pictures of people reading my book from all over the world. Malaysia, Rwanda, across Europe, in Asia. And it’s amazing.

NC: What can non-Israelis learn from this Israeli mentality, the Israeli mindset?

IA: Chutzpah is actually about skills, muscles that are extremely critical for the success of everyone. In 2020, and going forward. And these are the skills that we, as people, will need.

The first step is understanding which skills we’re talking about and then it’s about practicing, taking ownership. Things like creative thinking and critical thinking, and questioning, and challenging authority, and teamwork and leadership versus management – these aren’t the same things – and coping with failure and so many other different skills. I list 17 skills in my book.

And if I had to choose the most important one, it would be dealing with ambiguity and uncertainty, and understanding the world has changed. The world is an uncertain place – not unsafe – but uncertain in every way. In economics, politics, climate change, social demographics. There are shifts in every aspect.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThe way I see it: We have no other choice as human beings to accelerate our capability to cope with this uncertainty.

Now, how can we do that? It’s feasible, it’s very challenging and it requires a lot of attention, but it’s doable.

So if I had to choose the one thing that non-Israelis should take away from reading my book, I would tell them: Start looking at the world around you, wherever that is, look at your core, and start expanding into your community, your workspace, your city, or country wherever your fields of interest are. And accept the fact that you are one human being among many, living with this uncertainty, and start to question and learn to cope with this reality.

NC: That could be quite hard for some people to do, especially those who grow up in societies that value a certain type of order and structure.

IA: That’s true but it’s hard for everyone. Uncertainty is hard. Certainty provides a sense of control.

NC: I want to ask you about some of the downsides of chutzpah. When does it become an obstacle or plays to a disadvantage?

IA: One of the concepts I talk about in my book is analysis-paralysis. If everyone has an opinion about everything and all opinions are equal, how do you reach a decision? Listening to all opinions does not mean that a decision will not be made by the right person – whoever that person is.

But it becomes a problem when you don’t know how to draw the line between hearing opinions – genuinely listening to what people have to say – and then having to make a decision. That’s the whole concept of analysis-paralysis, where there are too many opinions and you get paralyzed because you’re listening to too many experts. And that can become inefficient.

Look at traffic in Israel, for example. You step into your car, you’re ready to go, and you’re literally afraid. It’s a war zone. Now I don’t know statistically if there are more accidents in Israel than elsewhere, but even if there aren’t, just the feeling of driving while being so alert is not positive.

The road is an example of where chaos combined with intensity and too much flexibility creates an unpleasant and inefficient situation.

There’s also the “ihiye beseder” (“it’s all good” or “it’s going to be fine”) mentality. In 2018, there was this incident where these teenagers were taken on a hike [near the Dead Sea] as part of this beautiful mechina [pre-army] program, and despite the weather warnings, they went, and the organizers thought “we’re ok, we’re cool, we’ll be fine” and it ended in an extremely tragic way [nine teenagers were killed in a flash flood]. So that’s the downside of the whole concept of “ihiye beseder.”

What I’m trying to say in the book is that it’s not black and white, it’s not binary. And I’m often asked what is the right balance. But actually there is no formula. The balance changes according to environment or setting. It’s two sides of the same coin. The positive and the negative coexist.

So, for example, you can be an opinionated individual and still recognize and value the strength of a team and your contribution to that team and vice versa. So it’s not either you’re an opinionated person and everything has to be your way or you’re part of a team and you guys agree on everything. There is coexistence and this is where the magic happens.

These balances are very hard to achieve but I think it’s possible.

And that’s how I look at the price of chutzpah. There is obviously a price. But there’s also a price to being super structured and super organized.

NC: So how do you bridge the understanding gap, especially in the business world, where non-Israelis may misunderstand some of this chutzpah or see it as uncalled for, even offensive?

IA: I’m not proposing a solution and saying “this is the way things should be done.” I’m proposing a mindset, a humanistic approach to human beings. These methodologies that I speak about that were developed here for the Israeli military, were developed out of necessity. It’s about having a very limited amount of information about individuals and in a very short period of time, and the need to identify personality traits and skills within those individuals. This is exactly where the world is headed now because formal credentials are becoming less of an identifier of potential.

Many super smart and super talented people today decide not to go to university. More than in the past. So if they lack that part in their CV, does it mean they’re less talented? Some of them, no, and you don’t want to miss these people. They might be your star.

So how do you reassess potential? We used to assess potential based on past achievements and, in my opinion, that’s not relevant anymore. With people changing positions and industries and staying for shorter amounts of time in certain positions and moving to other roles – this wasn’t the case in the past – you need to constantly reassess their capabilities and their skills, And not specifically what they’ve done in the past because what they’ve done in the past may not tell you anything about their future.

And that’s why these core capabilities are so important.

So, for example, I was in a strategy session with partners in the US. We were two Israelis and two Americans in a strategy meeting. And we came prepared, we called the meeting a strategy brainstorm session. That was the purpose of the meeting, and it went on for about two and a half hours. And when we finished the meeting, one of the Americans took me aside and asked me “what happened in there?” And I said “what do you mean? What happened?” And he said “why did you guys argue so much” and I responded, “what do you mean?” And he said, “you and the other Israeli were always arguing, aren’t you in agreement?” And I said “we were just having a conversation. This was a brainstorming session. Wasn’t that the goal? To have a brainstorming session? We have a great outcome, don’t we?” And he said “yes.” So I told him “have you ever seen a silent, pleasant storm? That’s what brainstorming is all about – it’s a storm.”

I realize that this experience for him was a bit overwhelming but I reflected that to him and told him that my Israeli colleague and I were totally okay, we were in agreement and that it’s a mechanism to think together. So instead of just agreeing with each other at every turn, we’re challenging our thinking and we’re not afraid of confronting each other for the sake of achieving a better result.

So the optimal outcome of the meeting was a strategy for the company which was different than what we first had in mind. Because that brainstorming session helped us refine it and improve it and enrich it.

And that’s a good example of the importance of words. Words, in my opinion, have a lot of meaning but sometimes we don’t focus on that. So a brainstorm – if you’re capable, if you have trust, if you create the right environment – can definitely be a storm of ideas. And then beautiful things happen.

NC: Israelis are said to embrace failure, to accept it, to even expect it. There’s this idea that if you haven’t failed you haven’t actually ‘done,’ you haven’t lived. What’s your take on failure?

IA: The weight, the gravity that comes with the word ‘failure’ is already different here in Israel than elsewhere. One of the reasons, I think, that Israelis are so okay with failure is because they don’t give it so much weight.

Like we said in the beginning, they don’t have time [laughs] You’re not going to spend time thinking about the failure and thinking about what you could have done differently and how it could have played out differently. However, there is a debrief because we’re not afraid to ask questions and to confront any mistakes. But it’s not for the sake of doing a deep analysis of the failure, it’s for the sake of learning. There’s a big difference.

Think of it as a young child. Until they start walking, there is a lot of so-called failures, they fall hundreds or thousands of times – someone must have counted – until they actually take their real first steps. They don’t just get up and start walking. It just doesn’t work like that.

So when you realize that and you’re not afraid of making mistakes, you come to understand that the outcomes will not always be what you planned for them to be.

The big question is what do you do when you realize that? Are you open enough, are you flexible to course-correct? Sometimes you have a specific plan which is headed for failure and you need to change the course you’re on so it can become either a success or at least a non-failure. You always have options and there are many decisions that you can make, there are always alternatives. But people sometimes just stay so focused on goals that they’ve defined and views they have, and outcomes they’re looking for, they’re not flexible enough to adapt and be very agile in their thinking and react to what’s happening and correct course.

The biggest failure for me would be to be too rigid.

NC: We interviewed you in 2017 about Israeli women’s share in the tech ecosystem and feelings of discrimination and disadvantage. At the time, you felt that your own personal career path was not hindered by gender discrimination or a glass ceiling. Do you still feel that way?

IA: I do but the one thing that has changed for me is that I realized that there are a lot of women who need role models. Specifically female role models and that’s the one thing that I realized and that has opened my eyes. And I’m here to offer that for women who need it.

So I’ve become more involved in different activities, different women’s groups, mentoring and so on.

I still strongly believe that being present – I’m not saying that the numbers are good or optimal but I think it’s not a “woman problem.” It’s something that we need to address together – everyone, men and women.

I have three boys. Does that mean that I don’t need to give them a role model about women? No, I want them to make the right decisions at work or in their social lives regarding themselves and the women around them.

I still think it’s very important that while we provided role models, while we encourage and empower women in different settings, and different stages and different practices, we keep doing that as a whole community. Not just women for women. It has to be everyone working toward this very important goal which is equality in our society.

The second thing I want to say is that the numbers are getting better and better. We see women founders and women in executive roles and so we have some slow movements but there is a trend there. We can try to accelerate things, definitely, but it’s happening.

NC: What did you learn from writing your book, what did you take away from it?

IA: I love this question. I haven’t been asked that before. So thank you for asking. I learned a lot during this process. About so many things. Personally I’ve learned that if you work hard and you put your mind to it and you create the right setting and tools – if I wrote a book published by Harper Collins in the US about Israeli childhoods – you can do almost anything you want but it takes a lot of hard work and intent and thought put into it.

I never thought I would write a book until I decided to write one.

The second thing I learned is that with all the differences and the gaps with Israeli society, internally, and between Israel and the US, and people of all ages and backgrounds etc, we’re all human beings who are complex and holistic and who come to this world with good energy and good intent. Our story is what we do with all that. Maybe it’s a bit naive but I really believe this.

And it’s really remarkable for me to see people from different places and of different generations reading my book and it makes them think, and it makes them feel, and ask questions and they go out and do things. That’s amazing and it’s a good feeling.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments