Researchers from Shaare Zedek Medical Center and Bar Ilan University are working with investors to raise $1 million to fund research and development for eye drops they say can correct refractive-related vision problems, thereby potentially making eyeglasses obsolete.

The development of the eye drops, dubbed “nanodrops,” was first announced in March 2018 by Dr. David Smadja, a research associate at Bar-Ilan University’s Institute of Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials (BINA) and the Head of the Ophthalmology Research Unit at Shaare Zedek. Smajda led a team of ophthalmologists working on the solution, including Professor Zeev Zalevsky of Bar Ilan’s Kofkin Faculty of Engineering and Professor Jean-Paul Moshe Lellouche of the Department of Chemistry at BINA.

Made up of a synthetic nanoparticle solution, the eye drops have shown great potential to solve cornea-related vision issues. In the team’s first round of animal trials in March, the nanodrops were applied to pigs’ corneas and successfully corrected two kinds of refractive errors: myopia (near-sightedness) and presbyopia (far-sightedness typically caused by aging).

SEE ALSO: Israeli Doctors Develop Revolutionary Eye Drops That Could Replace Glasses

“In these first bio-activity tests, we demonstrated that these drops are incredibly effective,” Lellouche tells NoCamels.

The three researchers behind the nanodrops (from left to right), Dr. David Smadja, Prof. Zeev Zalevsky and Prof. Jean-Paul Moshe Lellouche. Courtesy

The inspiration for the eye drops came from Dr. Smadja who suffered from headaches for years from working at his computer for long periods of time. He knew he needed a small visual correction, but his choices were limited.

“My correction was so small that I was not eligible for any laser operation,” Smadja tells NoCamels. “My options at the time were [either] wearing glasses or wearing contact lenses.”

Dr. Smadja recognized that the standard solutions for visual correction failed to cure dry eyes, a symptom common among screen users, and decided to create a better alternative: “I thought, why not make eye drops that could correct my vision with a refractive index?”

The team plans to further test the drops on live rabbits this year, before moving on to human trials in 2020.

During these trials, the researchers will test the drops on subjects with “any type of refractive error that enter into the scope of the nanodrops,” Dr. Smadja describes, for the aim is to correct different kinds of refractive errors. “In the end, we plan to have eye drops for myopia (nearsightedness) and for hyperopia (farsightedness),” he adds.

They will also address remaining issues regarding the functionality of the drops.

“First, even though the pigs’ corneas are very close to the human eye, we don’t have any feedback in terms of how long the effect will last,” Dr. Smadja explains. It is estimated that users of the drops will experience visual correction for at least two to three days, which the team hopes to verify using the subjects’ verbal feedback.

Dr. Smadja adds that the human trials also provide the opportunity to test the nanodrops against the alternatives: “We want to compare the drops against glasses, and we can’t quite do that with animals.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

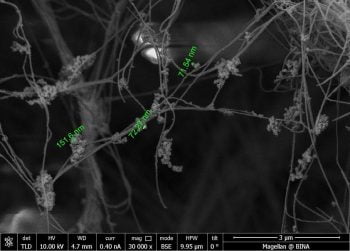

A scanning microscope looks at the corneal incision in the pig’s cornea in which the solution has been applied and uses very high magnification to identify nanoparticles. The tiny, hyperreflective, and encapsulated balls are measured at 40 to 90 nanometers in diameter. Courtesy

The researchers are currently working with their team of investors to build a biotech startup around the nanodrops. They plan to promote their invention through this company with the expectation of placing the product on the market by the summer of 2020.

Smadja says the team intends to sell the drops at a competitive price – somewhere between the price of eyeglasses and the price of contacts.

“The idea is not to create a product that will be much more expensive than its alternatives,” he explains.

In addition to the nanodrops themselves, the researchers are developing a small, smartphone-compatible laser device that will allow patients to easily apply the drops at home using a mobile application.

“Once you have your prescription, you enter this number into a computation software that we developed, and we match specific patterns to your number. The laser painlessly marks a tiny spot and etches a pattern on the corner of the cornea,” Smadja explains. After a pattern has been etched, the patient applies the drops to the eye, and the nanoparticles inside the drops activate the pattern.

Dr. Smadja stresses that “the laser we are talking about is not like the laser used for complicated optical procedures,” and that the application process, while seemingly complicated, is simple and non-invasive.

Although they have yet to finalize a market strategy, the researchers plan to differentiate the consumer experience surrounding the nanodrops from the often-complicated process of buying glasses or contact lenses.

“These nanodrops do not need to be personalized,” says Professor Lellouche.

“The difference between people will be the pattern corresponding to their prescribed number,” which will only be reflected in the application process, Dr. Smadja explains.

NOTE: An earlier version of this article stated that the researchers raised $1 million. The article was amended on January 3, 2019 to reflect that they are currently raising the funds and have not yet completed the process.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments