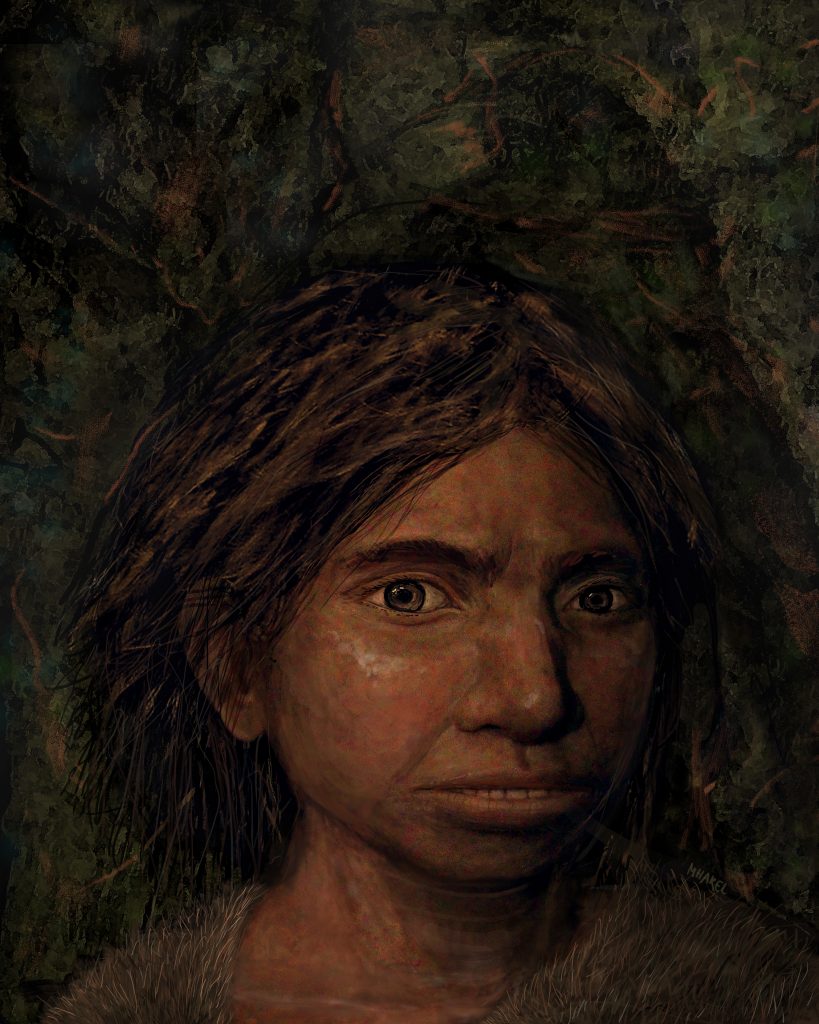

A new, innovative Israeli DNA study has revealed what an ancient relative of modern humans from some 100,000 years ago could have looked like.

Scientists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) unveiled late last week a 3D reconstruction as well as portraits of Denisovans, a mysterious, extinct group of archaic humans, based on patterns of chemical changes in their ancient DNA. These reconstructions paint the first known anatomical profile of Denisovans who have remained elusive due to very few discovered physical remains. The entire collection of known Denisovan remains include a jawbone with two complete teeth and a pinky bone.

SEE ALSO: Preserving the Future: Israeli Researchers Unveil New Coding Technique To Store Data On DNA

The findings on the jawbone, first discovered in the 1980s in the Tibetan Plateau, were made public earlier this year, sending a buzz through the science and archaeology worlds. The specimen dated to approximately 160,000 years ago, and was the first such fragment found since 2010 when DNA collected from a fossilized finger bone in the Denisova Cave in Russia’s Altai Mountains revealed the previously unknown hominin group, considered separate from humans and Neanderthals. At the Denisova cave, Denisovans and Neanderthals also appear to have bred; a bone fragment from the cave was found to have belonged to a female who died around 90,000 years ago, the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

The jawbone found in Tibet confirmed that Denisovans were more widespread than previously thought. In 2017, a Chinese-American team presented their study of two partial skulls discovered a decade prior near the city of Xuchang in China’s Henan province dating between 105,000 and 125,000 years ago. They are also believed to have belonged to Denisovan members, but this has not been confirmed.

Denisovans went extinct some 50,000 years ago for reasons that are not yet known, but a number of studies from this decade say that “Denisovan ancestry of up to six percent was detected in present-day Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians and to a lesser level in East Asians, Native Americans, and Polynesians,” according to the research.

Also, “Denisovan DNA likely contributed to modern Tibetans’ ability to live in high altitudes and to Inuits’ ability to withstand freezing temperatures,” according to the Hebrew University statement.

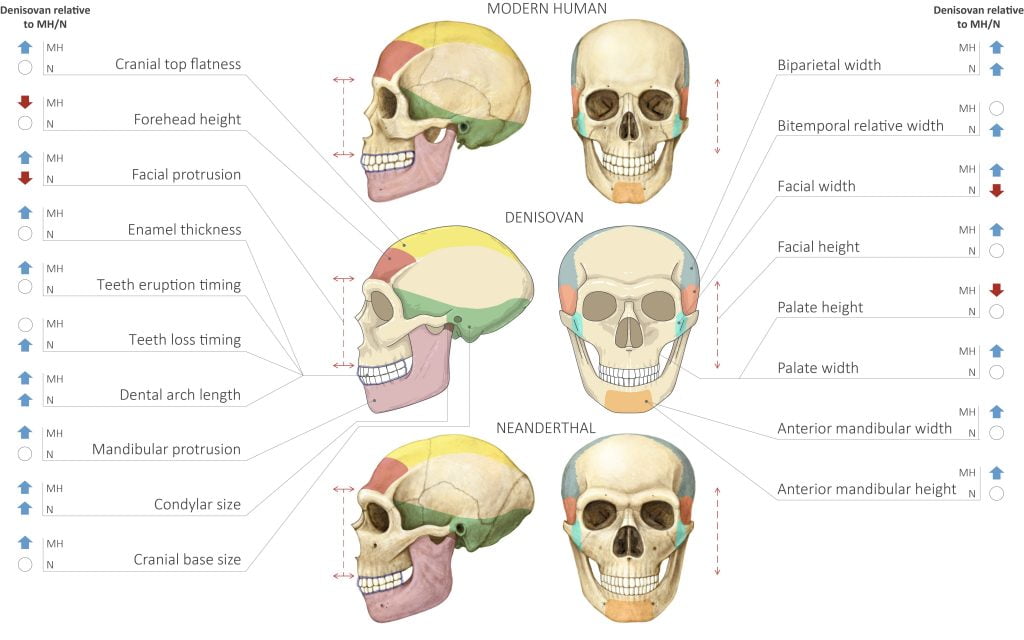

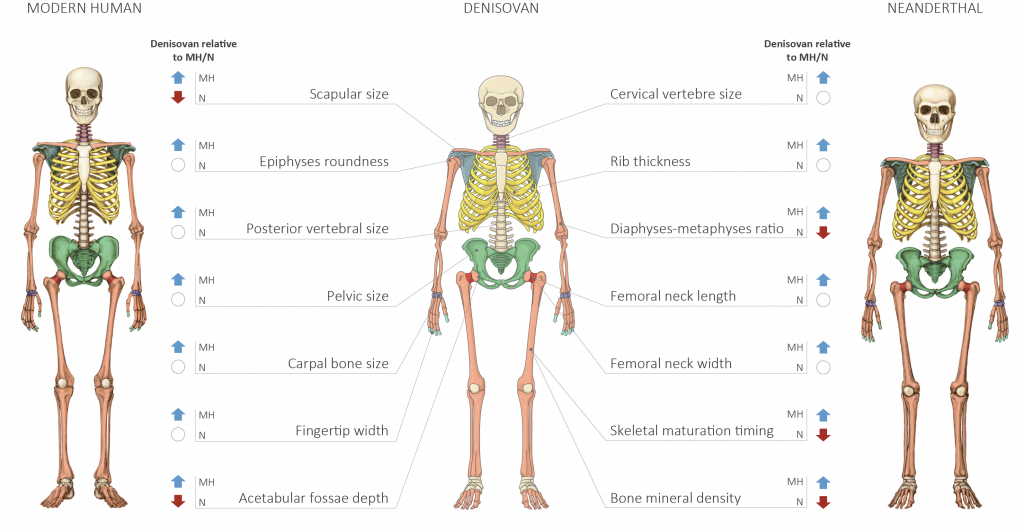

In their study, the Israeli team led by Professor Liran Carmel of HUJI’s Institute of Life Sciences and Dr. David Gokhman, a post-doc researcher at Stanford University, identified 56 anatomical features in which Denisovans differ from modern humans and/or Neanderthals. A majority of the differences were noted in the skull. For example, the Denisovan’s skull was probably wider than that of modern humans’ or Neanderthals’. Their molars also differ in their cusp, root morphology, and size. And the jawbone was shown to be robust, protruding, with a long dental arcade and no chin.

The scientists’ method was detailed in a study titled “Reconstructing Denisovan Anatomy Using DNA Methylation Maps” published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Cell. The study spanned three years of “intense work” with DNA methylation maps, in reference to chemical modifications that affect a gene’s activity but not its underlying DNA sequence.

According to a university statement, the researchers began by comparing DNA methylation patterns among the three human groups (modern humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans) to find regions in the genome that were differentially methylated. Next, they looked for evidence about what those differences might mean for anatomical features—based on what’s known about human disorders in which those same genes lose their function.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“In doing so, we got a prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change—for example, a longer or shorter femur bone,” Dr. Gokhman explained in the statement.

The team said it tested performance by reconstructing Neanderthal and chimpanzee skeletal morphologies and found that approximately 85 percent of their trait reconstructions were accurate in predicting which traits diverged and in which direction they diverged. They applied this method to the Denisovan and were able to produce the first reconstructed anatomical profile of the group.

“In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals but in some traits they resembled us and in others they were unique,” said Professor Carmel.

In their Cell study, the research team suggests that Denisovans likely shared traits such as an elongated face and a wide pelvis with Neanderthals, and also identified “Denisovan-derived changes, such as an increased dental arch and lateral cranial expansion.”

“Our study sheds light on how Denisovans adapted to their environment and highlights traits that are unique to modern humans and which separate us from these other, now extinct, human groups,” Carmel said in the university statement.

During the research, the team received welcome validation, “One of the most exciting moments happened a few weeks after we sent our paper to peer-review. Scientists had discovered a Denisovan jawbone [in Tibet]! We quickly compared this bone to our predictions and found that it matched perfectly. Without even planning on it, we received independent confirmation of our ability to reconstruct whole anatomical profiles using DNA that we extracted from a single fingertip.”

The researchers write that their prediction work “match the only morphologically informative Denisovan bone to date, as well as the Xuchang skull, which was suggested by some to be a Denisovan,” in references to the skulls found in eastern China.

“We conclude that DNA methylation can be used to reconstruct anatomical features, including some that do not survive in the fossil record,” they wrote.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments