Israel’s most educated population is leaving the country at a pace that should “ring alarm bells in all of the corridors that determine Israel’s national priorities,” according to a new report released this month by the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research headed by Professor Dan Ben-David, a leading Israeli economist at Tel Aviv University.

In the detailed study named “Leaving the Promised Land: A Look at Israel’s Emigration Challenge,” Ben-David shows that as Israel has become more integrated into the developed world, a rising share of its college graduates has been emigrating, particularly those with advanced degrees in exact sciences and engineering – who make up the foundation of Israel’s high-tech sector – physicians, and academic researchers.

While nine million people live in Israel, “it is an exceptionally small number of Israelis – less than 130,000 persons – that is keeping the economy, the healthcare system, and their underlying university bedrock near the pinnacle of the developed world,” the report reads.

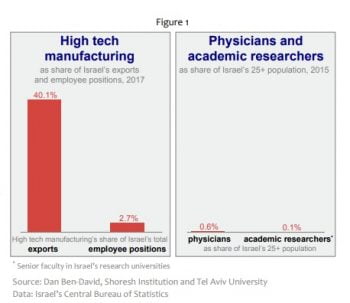

According to the research based on figures from Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, just 2.7 percent of all employee positions in Israel are in high-tech manufacturing fields, which accounted for a staggering 40.1 percent of Israel’s total exports in 2015. Meanwhile, the total number of research faculty in Israel’s eight universities (regardless of research fields) is just 0.1 percent of Israel’s population 25 years old and up, and physicians account for just 0.6 percent of all persons ages 25 and up.

“What we tried to do is look at a smaller group that makes up the primary engines of the Israeli economy: those who provide healthcare, those who teach everybody, and those in high-tech,” Prof. Ben-David tells NoCamels in a phone interview.

“It’s a small group, but these people play a major part in what makes Israel a first-world country; they are keeping Israel in the modern world,” he adds.

Emigration by a critical mass of the total, even if it numbers in the tens of thousands, “could generate catastrophic consequences for the entire country,” the report he authored notes.

Ben-David wrote that “the extent of emigration, the direction of the trend, and the direction that all of Israel – a country that needs to remain sufficiently attractive to those who are very sought after by other countries – is headed should ring alarm bells in all of the corridors that determine Israel’s national priorities.”

The study shows that of the nearly 600,000 Israelis who earned their academic degrees between 1980 and 2010, 5.8 percent with BA degrees have been living abroad for at least three consecutive years in 2017, while 4.5 percent of those with MAs have been doing the same. Of those with PhDs, over 11 percent moved abroad.

And while some return, in 2017 the ratio of persons with an academic degree leaving Israel for each who returned was 4.5, up from 2.6 in 2014, according to the research.

The highest rate of emigrants from Israel are graduates of research universities with degrees in exact sciences and engineering which stands at 9.2 percent, according to the study.

Israel’s economic engine is fueled by the technical fields, which highlights the challenge created by emigration rates among these graduates, the report says.

“In the high-tech sector, the markets are already abroad,” says Ben-David in reference to the industry’s global outlook as the country’s local market is small and limited. “There’s pressure to relocate already in these fields, and then there’s the issue of labor productivity: Israel has very low labor productivity and you can’t get high wages if there’s no productivity, so there’s a growing gap between what they can earn here and what they can earn abroad,” he explains.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

A figure in the Shoresh report on Israel’s brain drain showing the share of Israeli physicians abroad. Screenshot

In the medical field, the numbers are also alarming. The study shows that over the past decade, the number of Israelis earning their medical degrees abroad went from 37 percent (of the total number of Israelis receiving their medical degrees in Israel) in 2008 to 52 percent in 2017, owing to a lack of national resources bring out into educating physicians.

“When so many Israelis study medicine abroad, it should not come as a surprise that many also choose to live and practice abroad afterward. The number of Israeli physicians in the United States, for example, is the fourth highest among all source countries,” the report reads.

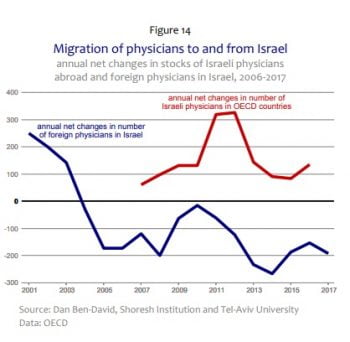

The share of Israeli physicians working abroad rose from 9.8 percent in 2006 (of the total share of physicians working in Israel) to 14 percent in 2016, according to the report, and while the number of foreign-trained non-Israeli doctors living in Israel had been increasing until 2003, the outflow has surpassed the inflow.

SEE ALSO: Israel Sees Slow But Growing Integration Of Arab Community Into High-Tech Sector

In the academic field, the study focused on tenured or tenure-track positions in the top 40 American academic departments across a number of different fields, excluding adjunct, clinical and other semi-permanent positions, as well as visiting Israeli professors and tenured faculty who also hold positions in Israel. The share of Israeli faculty in US universities has risen sharply in the fields of philosophy, chemistry, physics, economics, computer science, and business.

“To give a sense of the magnitude involved, the number of temporary Israeli scholars in US universities was nearly 1,700 in recent years whereas the total number of senior faculty in Israel’s eight public universities equals about 4,900,” the report reads.

Ben-David tells NoCamels the first thing Israel should do is implement an overhaul of its education system which he says is sorely lacking, change its electoral system, and begin pouring resources into national infrastructure and healthcare.

“About a quarter of Israeli pupils are from the Arab communities where their math and science levels are below third-world. Then you have about a fifth of the children – those who are ultra-Orthodox – who do not study a core curriculum. Israel is the only developed country in the world that allows parents to deprive their children of a core curriculum,” he says. In the periphery, outside central Israel, the education system is also inferior.

Israel needs “a uniform core curriculum, for all kids of all communities, we need teacher training and better compensation for them, better screening, and we need to overhaul the Education Ministry which just swallows up money and is very inefficient,” he tells NoCamels.

At the moment, Israel operates “like an engine that’s not using all its cylinders,” Ben-David says, calling for urgent attention to the matter.

“We have to do something about this tomorrow morning. A third-world economy cannot support a first-world army, and we can still fix it,” Ben-David tells NoCamels, suggesting the direction the country is headed in will have a detrimental impact on its security situation.

Israel’s politicians, meanwhile, who set the national agenda, “are arguing about chairs on the deck of the Titanic,” he says.

“Programs to draw back those who have left with incentives like slightly higher wages, bonuses, and the like, will not work without the shifting of national priorities: investing in better roads, easing congestion, building more hospitals,” Ben-David warns.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments