“When an Israeli thinks you are mistaken,” writes organizational consultant Osnat Lautman in her books on Israeli business culture, “he simply says, ‘You’re wrong.’ When you ask for his opinion, he assumes you really want it, and gives you an honest and straightforward answer.”

For anyone who has worked with Israelis – or is Israeli – the next immediate thought is likely, ‘uh oh. Now what happened?’

Although it’s 2019 and many business collaborations are already underway (and thriving), the gap between how business is done in Israel and how it is done internationally is wide, says Lautman.

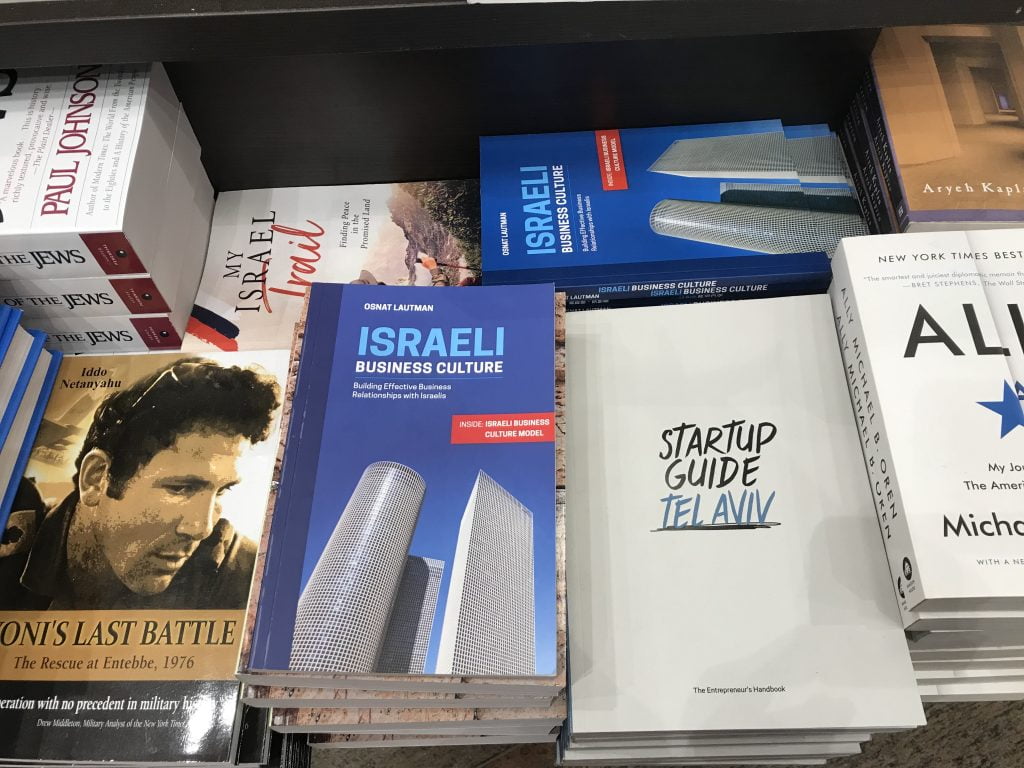

Lautman’s book on Israeli business culture is an Amazon bestseller. It is also a popular choice in the duty-free bookstore at Ben Gurion International Airport outside Tel Aviv, according to its author.

“Non-Israeli business people buy it on their way home, after being here for a few days. They feel the need to buy this book to understand what just happened in their business meetings here,” Lautman tells NoCamels about her guide “Israeli Business Culture: Building Effective Business Relationship with Israelis.”

From manner of speaking to work habits to the importance – or lack thereof – of workplace hierarchy, understanding a person’s culture has a very important bearing on their way of doing business.

“Even if we speak English as a second language, we still need to understand that the roots are different. We grew up in a different place, we were taught differently, we think differently,” says Lautman. “We need to understand that those values bring different behavior and ideas to the work arena. We need to learn what advantages to take from each culture to the diverse working arrangement.”

In 2015, Intel USA made headlines when its internal guide to doing business in Israel was shared on Facebook by a local hire. “Israelis are generally fond of debate and will typically discuss any topic very passionately … visitors are often taken [a]back by the tone or loudness of the discussion,” read a slide from the Intel USA manual “Working with the Israelis.”

The Israeli response to Intel’s guide was one of giggles. Israelis laughed at themselves, laughed at how others saw them, and laughed at the situation as a whole.

But Lautman, who is a cross-cultural expert and consults for firms, governments, and individuals, says that not understanding the other side, and how they view us, can potentially be detrimental in the world of business. She believes cultural understanding is critical for business success.

“Many Israelis do not understand how big the gap is. There’s still the point of view, ‘we’re the startup nation and people will get over it if we were a bit aggressive or too informal,’” says Lautman. “Those who want to grow their companies into multinational entities, with an Israeli at the head, need to educate themselves and understand the culture of the other. When we incorporate a business etiquette of listening, politeness, etc., in our dialogue, we will achieve great successes.”

Cultural bridge in the business arena

People want to do business with Israel thanks to the country’s name as a hotspot for innovation. But understanding Israeli business culture is not always easy for foreigners.

After living and working in the US for a few years, and making her own faux-pas in the corporate world, Lautman took it upon herself to help close the “deep cultural gap” that exists in the business arena.

In 2015, Lautman published her first book to help readers understand Israeli business culture and build effective business relationships with Israelis. It contained 95 pages. In 2018, a second edition with 231 pages hit Amazon and booksellers’ shelves.

The book “combines a practical manual with vast conceptual knowledge about the Israeli business culture. Understanding cultural differences in business and in daily life interactions are fundamental for global success,” Grisha Alroi-Arloser, CEO of AHK Israel – Israeli-German Chamber of Industry & Commerce, writes in a review.

“In our increasingly changing and interconnected business world, this book gives Israelis and non-Israelis alike an opportunity to learn how to work successfully among diverse groups,” writes Roy Bick, founder and VP of Operations at Moovit.

The newest book edition comprises case studies and stories from 350 people from around the world whom Lautman has interviewed regarding their experiences of working with Israelis.

Lautman says readers – be they investors or entrepreneurs, CEOs or marketers – will often email her with a list of their own experiences and request her help when doing business with Israelis.

She has stories of CEOs writing long, detailed messages to a counterpart in Israel only to receive one answer, days later, with just one word in capital letters: NO.

For a foreigner, an all-caps, one-word answer, is the ultimate in rudeness. From the Israeli point of view, the short answer is a part of how we speak.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe“Modern Hebrew was formed with the desire to create …a relatively simple language that new immigrants could acquire. Israelis have to use direct, immediate, easy words and syntax without much fancy diplomacy – the Hebrew language – in order to communicate with each other. It’s an integral part of their culture,” writes Lautman.

There are also stories of Israeli entrepreneurs writing emails with the word “urgent” in the subject header, when in fact, the request had no urgency whatsoever, leading to a “cry wolf” situation.

In Israel, the word “urgent” is used to get a reader’s attention. But in Western culture, explains Lautman, ‘urgent’ means top priority. Lautman tells of an Israeli company that asked for something urgently but didn’t pick up the product until two or so weeks later, accidentally infuriating their foreign counterpart as a result.

And there are stories of foreign business executives feeling personally attacked during a meeting with Israeli counterparts who argued – usually in loud tones – about some aspect at hand.

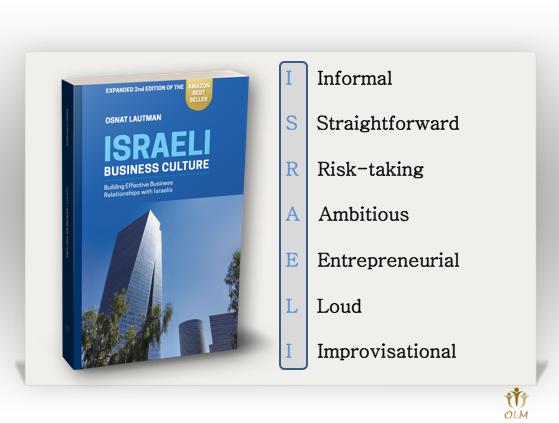

So, Lautman created an acronym, spelling “ISRAELI”, as a model to elaborate on these unique Israeli business characteristics: Informal (“I”), Straightforward (“S”), Risk-taking (“R”), Ambitious (“A”), Entrepreneurial (“E”), Loud (“L”) and Improvisational (“I”).

“I is for Informal – not just how we dress, but also how we communicate with one another,” she writes in her book.

In an anecdote in her book, Lautman tells of a misunderstood “informal” moment when an Israeli executive arrived wearing jeans to a company event hosted by a New York office. In Israel, jeans are worn to everything, from trips to the grocery store, to business meetings, to weddings. The American team found the Israeli global director’s choice of attire utterly “discourteous” and unprofessional.

Throughout the book, each letter of the acronym is given its due share.

In addition to authoring the books, Lautman gives workshops and training seminars to Israelis and foreigners on how to do business and what to expect from one another.

When she sits down for a morning interview (Israel time) with this reporter (NoCamels), she’s already on her second cup of coffee – she says she’ll have five by the end of the day. She works at all hours of the day. Her clients are everywhere – in Asia, Europe, North America, Africa, Australia – so she doesn’t have a set 9-5 routine.

She also makes time in the afternoons to be with her three children, all under the age of nine.

While her guide was initially written for a foreign audience, the book’s sponsor, the Manufacturers’ Association of Israel, understood that Israelis could benefit from it too.

In her book, she gives examples of Israeli bloopers. After one workshop, Shai, an Israeli working in the US, told her how in not understanding the need for diplomatic speech, he had the tendency of making his American employees cry (non-intentionally) with blunt feedback.

Lautman gives another example of an Israeli employee who was fired from a foreign firm after he told the CEO, in front of others, that he “didn’t care” about the CEO’s idea. What he meant, of course, was that “he didn’t mind if the CEO wanted to change something.”

It wasn’t just a language barrier. If the employee had spoken to his manager first and respected the corporate hierarchy, instead of directly to the CEO, his job could have been saved.

Lautman is still researching the subject. She has created a culture calculator to find data on how Israelis perceive themselves. Questions include how you speak to a manager, whether personal life and professional life should mix, the importance of following a work plan, and how friendly is too friendly at work. For now, the data helps her when bridging the business cultures of companies in Israel and beyond.

And while some of the gaffes in Lautman’s book are laugh-out-loud funny, they cease to induce giggles when a deal is missed or a CEO is offended.

“We [Israelis] were taught to say no, to think differently, to take risks,” she sums up. “We need to learn to think in an international language and to understand the business cultures of others.”

Viva Sarah Press is a journalist and speaker. She writes and talks about the creativity and innovation taking place in Israel and beyond. www.vivaspress.com

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments