A severe shortage of skilled workers in Israel’s high-tech sector is posing an important challenge to the industry and to the Israeli economy as a whole, according to two separate reports issued this month, one by the socioeconomic research institute The Taub Center and the second by Start-Up Nation Central (SNC) in collaboration with the Israel Innovation Authority (IIA).

The reports echo similar conclusions reached last year that showed that while Israel’s tech sector is nothing short of a success story, the industry has not grown by much in recent years and the rest of the Israeli economy doesn’t follow suit.

Last year’s report by the Israel Innovation Authority also showed a tech workers’ shortage of some 10,000 while this year’s findings showed a shortfall of 15,000 due to what SNC called a “demand for tech talent is rapidly increasing” while “not being matched by the supply of programmers, scientists, and engineers.” SNC says more small firms with between 11-50 employees responded to this year’s survey, with a total of 362 participants, allowing for a better picture, and that last year’s numbers were likely underestimated (with just 91 responding companies).

SEE ALSO: Israel Sees Slow But Growing Integration Of Arab Community Into High-Tech Sector

According to the SNC-IIA 2018 report, the largest number of open positions, at 31 percent, is in software and engineering specialties like DevOps, Front-end and Back-end, with significant shortages in Data Science, Machine Learning, and AI. Companies of 11-50 employees and largest companies of over 500 employees have the largest number of openings, according to the findings.

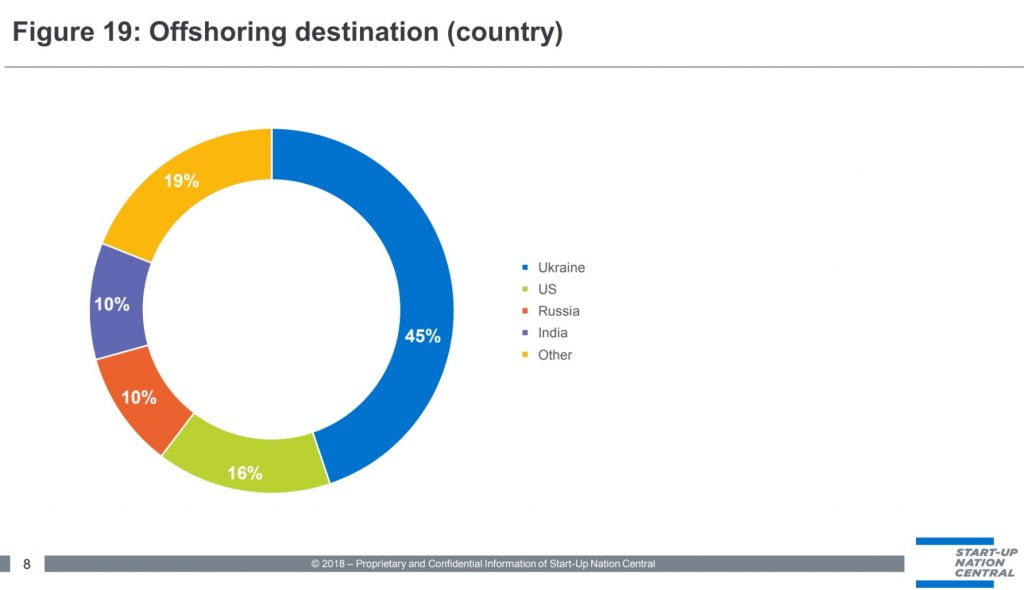

As a result, “Israeli technology companies, looking for talent and cost reduction, are increasingly establishing offshore R&D facilities in locations that offer quality talent at a reasonable cost,” SNC says, adding that “every fourth company reports having an overseas development team, with Ukraine being the most favored location.” Half of the companies established their offshore operation over the past two years, and now employ about 20 percent of their entire workforce overseas.

A slide by Start-up Nation Central showing top offshore destinations for Israeli companies.

The Israeli government, meanwhile, embarked on a number of programs to help answer the shortage, and “expand the pool of high-tech talent, including increasing the number of university and non-academic quality program graduates, working to realize the potential of underrepresented populations in the high tech sector such as women, Arabs and the Ultra-Orthodox, and facilitating the integration of returning Israelis with tech experience, as well as promoting the arrival of foreign experts,” notes Aharon Aharon, CEO of the Israel Innovation Authority.

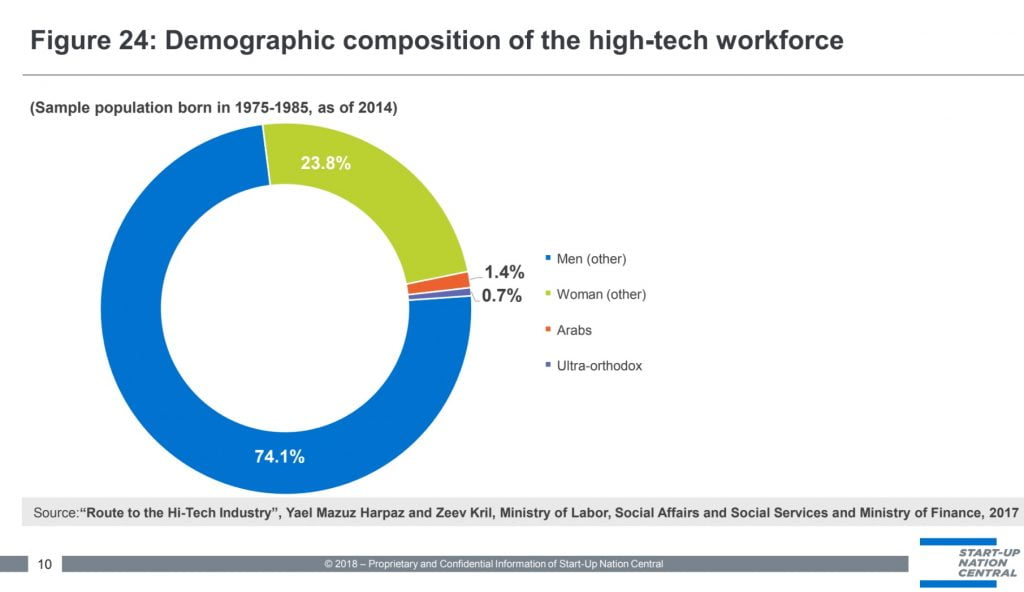

Women, for example, comprise just 23 percent of tech professionals and only 16 percent of tech management, with the average firm employing a workforce made up of just 3 percent Arab Israeli.

“The high-tech industry is undergoing rapid growth and is unable to ‘catch up’ with the demand for skilled tech talent,” he says.

Professor Eugene Kandel, CEO of Start-Up Nation Central says “the high growth in demand for Israeli innovation, which is good news, exceeds the supply of the human capital the innovation sector needs. The Israeli government, NGOs, and the industry understand the importance of this task, and as a result of their actions, the supply of human capital has been growing over the last few years. Still, this report shows that even more rapid growth in human capital supply is required so that the sector can grow and satisfy global demand.”

Kandel says “current efforts to scale up the relevant training at universities and attract a much larger number of schoolchildren and young adults into tech education must be intensified,” but “without a massive integration of women, Arabs and the ultra-Orthodox into the sector, there is little chance of attaining the needed human capital.”

“The industry must start actively pursuing much wider pools of untapped talent,” he urges.

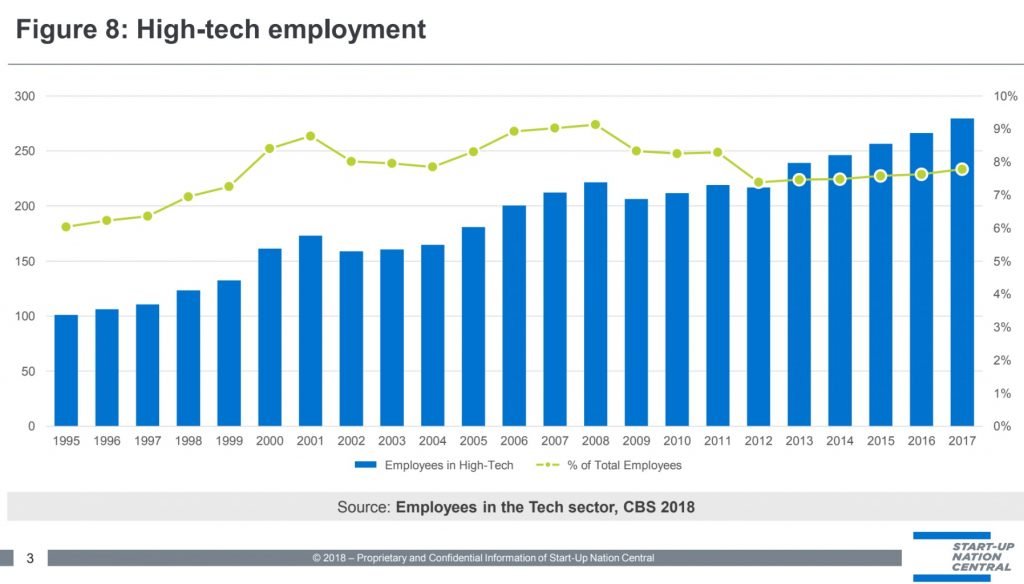

A slide showing the growth of the Israeli tech workforce. By Start-Up Nation Central

The Taub Center’s State of the Nation Report 2018, meanwhile, urges a different course of action, one focused on bridging the inequality and inclusiveness gap and seeking alternative sources for future economic growth.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThe Israeli high-tech sector accounts for just 8 percent of total employment in the country, but it is the most important part of the economy, producing about one-fourth of income tax payments in Israel and accounting for a major portion of the added value of Israeli exports, the report says.

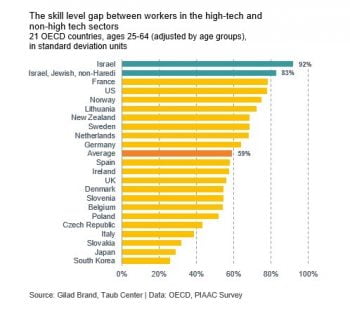

But the average skill level among workers in Israel is lower than the OECD average, especially among the ultra-Orthodox and the Arab-Israeli communities. Compared with the very high skills of Israel’s tech workers, the resulting gap is “among the largest in the OECD,” the Taub Center says.

The study’s findings show that, despite the success of the high-tech sector, the field does not appear to have much room left to grow due to this mismatch. Over the past five years, the number of people employed in the Israeli tech sector, as defined by the Central Bureau of Statistics, has grown from 240,000 to 280,000, but their percentage – at 8 percent – has remained stagnant. In addition, the report argues that most Israelis with the skills and abilities to work in high-tech already do.

A graph by the Taub Center showing the skill gaps levels. Via the Taub Center

“A large portion of the workers in Israel have low skill levels and therefore have low earning ability. The availability of cheap labor detracts from employers’ willingness to adopt advanced technologies and holds back the economy’s growth potential,” says the Taub Center’s Gilad Brand, the author of the report.

The report recognizes government efforts to expand the talent pool, including programs to raise computer science student quotas, create intensive career retraining initiatives with a specific high tech orientation (coding boot camps), and institute reforms to encourage higher level math study in high school, but argues that the potential for increasing high-tech employment through these projects is low, at least in the short term.

One important skill is English proficiency, which is very low among the ultra-Orthodox and the Arab communities, the report notes. According to Brand, “improving English instruction in these population groups’ educational institutions is a necessary step toward making the high-tech sector accessible to them.”

Brand also found that even science and engineering graduates who do not have high skill levels find it difficult to integrate into occupations relevant to their areas of study (both in Israel and other developed countries). “From this, we may conclude that offering high-tech retraining to workers whose skill levels are not high is of little value,” he writes.

A slide showing the demographic composition of the Israeli tech workforce. By Start-Up Nation Central

On a more positive note, the Taub Center says its data indicates an upward trend in the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population’s skill level, and an even more substantial improvement in the skills of the Arab Israeli community, especially in younger age groups. “Therefore, the potential for increasing the share of those employed in high-wage employment sectors, such as high-tech, will grow over time.”

Prof. Avi Weiss, President of the Taub Center, said in a statement that “the data consistently show high levels of inequality in Israel, which stem from large differences between the abilities of graduates from various streams of Israel’s education system. Therefore, providing incentives to retrain and move workers into the high-tech industry is not in and of itself an adequate response.”

Brand concludes that “focusing on improving the skills of low-skilled workers may yield a higher return than the investment needed to move higher-skilled workers, of which there are not many, into the high-tech industry.”

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments