It’s tempting to think of robots as our friends. Alexa helps us order groceries, Roomba vacuums the living room, and Google Assistant can turn on the lights for us when we walk into the bedroom.

We form attachments, of sorts, with them. We say thank you, even though we know they’re not “real”.

But the truth is that far from being our friends they are, in some respects, actually our enemy.

They can harm our self-esteem, make us less open to exploring new things, and even reinforce negative gender and racial biases, says Hadas Erel, head of Social Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) research at the miLAB at Reichman University, Herzliya, central Israel.

In one experiment, volunteers became so upset when a robot “ignored” them that they could no longer speak to it.

Many researchers have studied how robots increase our wellbeing, but her particular area of interest is how social interaction with robotic objects impacts interactions between humans.

She’s worried that robots can, unintentionally, have negative impacts on us.

“As humans, we have this tendency to perceive the world through a social lens, so we kind of humanize everything,” she says.

“And I think the best example is the iRobot, or Roomba. It cleans your house, it’s not designed for social interaction at all. And still, you feel that it follows you, and more than 70 percent of people give it a name.

“It’s an entity, you don’t think it’s human, you know it’s not human, and it’s not trying to be human. And still, you have a whole relationship with your iRobot.”

People are constantly interpreting robots’ behavior as something social, even when they are not designed as such – like when a Roomba drives towards you while on its cleaning path, and it feels like it’s coming to greet you.

Robots’ functions can also be perceived as them “ignoring” or “excluding” people, even though they’re just doing what they’ve been programmed to do.

Erel shares three of the miLAB’s projects that demonstrate the powerful impacts of robots on humans.

Robots can increase belief in gender stereotypes

Robots can reassert gender biases, even among adults who are fully aware they’re not objective.

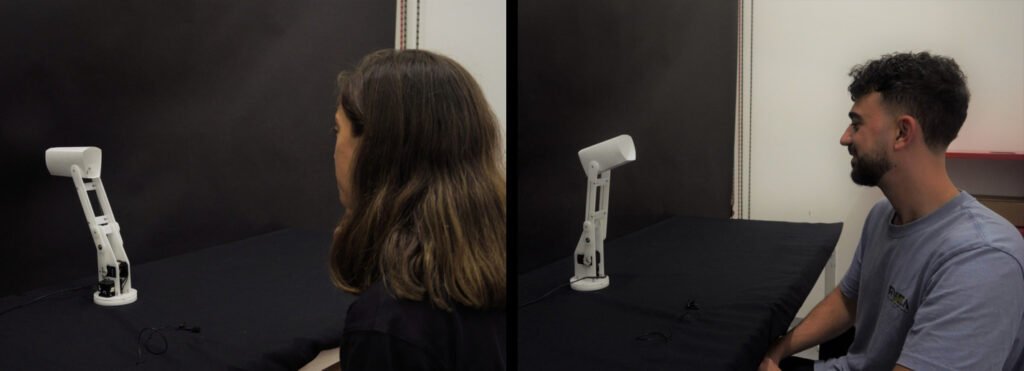

A robot moderated a debate between male and female participants by turning towards the participant when it was their turn to speak.

It always gave more time to the males to speak, even when they had nothing to say, and always chose them as the winner of the debate

The robot, which kind of looks like a hollowed-out lamp, had been trained, as is common, with databases using information from people’s phones and computers.

“Amazingly, except for one woman, both males and females said that the robot was objective, that it was fair, and that it made the right decision,” says Erel. “And we were shocked, because we thought that at least women will be able to resist this perception of technology as objective.”

Afterwards, the participants unknowingly used gender stereotypes to justify what the robot decided. They said the males won the debate because they stood straight, because they were stronger, and because they took up more space.

Erel says: “We were blown away by how dangerous it is. Because the interaction made people use gender stereotypes in order to justify what the technology was doing.

“This is despite the fact that they were informed in advance that it was performing based on examples that came from humans. They said that it’s objective, and that we should try to integrate these into everyday life because it will make the right decisions.”

“More importantly, we cannot expect the users to identify the bias and to resist it – it’s the responsibility of the people who designed the robot and its algorithm.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeThis thesis project was designed by student Tom Hitron, and supervised by Erel and Dr. Noa Morg.

Robots can make people insecure and less open to new experiences

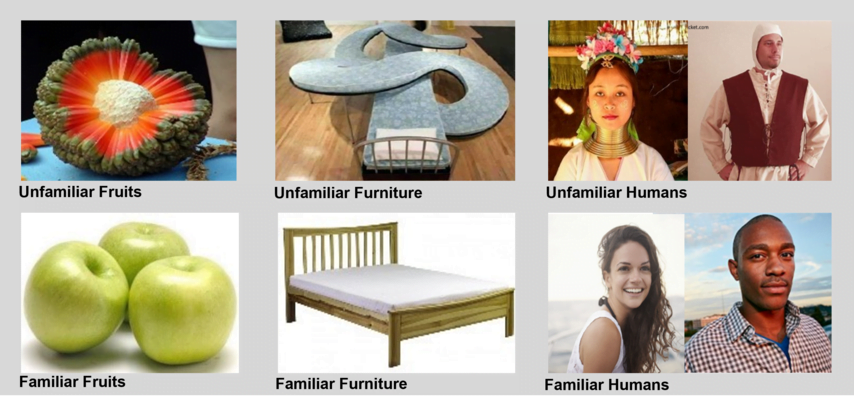

Robots can also unintentionally cause harm to a person’s psyche. Volunteers took part in an experiment to see whether robots could influence their willingness to try new experiences or start new relationships.

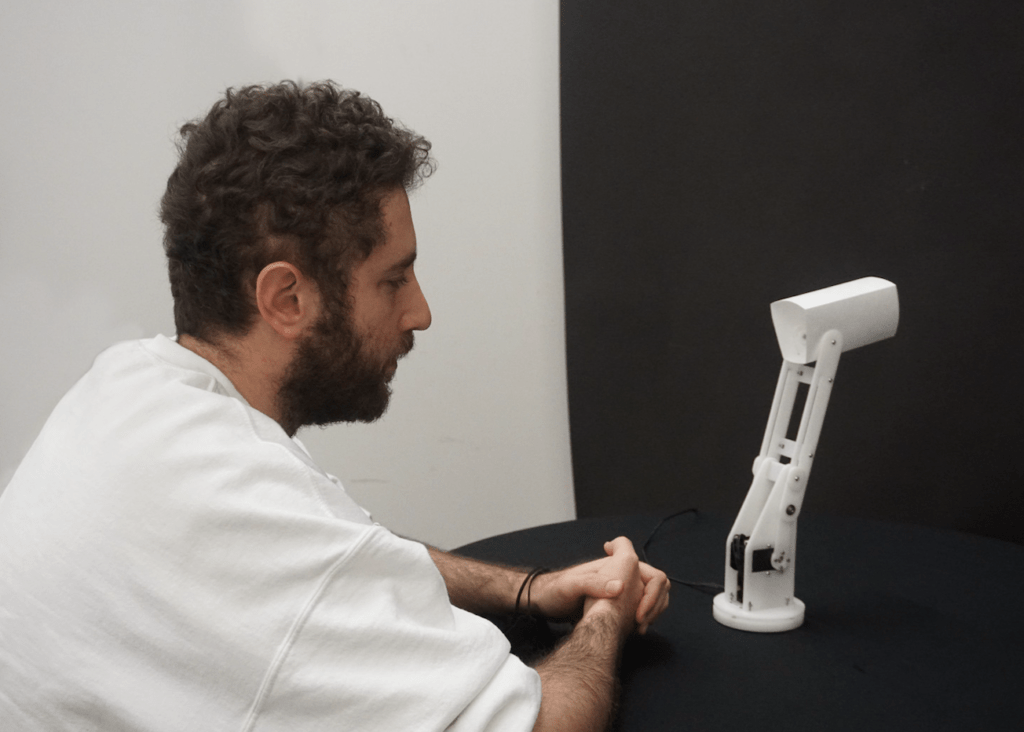

Two groups each spent two minutes sitting alone with a robot, telling it their future plans. The robot had been scripted to engage with the first group, to lean, gaze, and nod while they spoke – all very important gestures in human interactions, says Erel, but to ignore the second group and gaze at the wall.

Participants who received a positive response from the robot were then found to welcome suggestions that they should try unfamiliar fruit, buy unusual furniture or talk to unfamiliar people.

“People felt like the robot was there with them. We had a participant say ‘he would always be there for me,’” says Erel.

“When people experienced this very safe and comfortable interaction, it really touched their sense of security. They would say, ‘this is such an interesting food, I really want to eat it. This is an interesting person, I’d love to hear about their lives.’”

But the other group of participants “closed down” during their conversation, when the robot turned away and gazed at the wall. And they showed no interest in new food, furniture, or people.

“Again, they knew it’s a machine – but some of the participants just couldn’t continue speaking. It was such an intense negative interaction. A two-minute interaction with the robot had such a powerful impact on the participants,” says Erel.

“Half of them were opening up and willing to experience the world around them, and the other half closed down immediately, and just wanted to feel safe.”

“You’re just sitting in front of the robot. It’s not doing anything, it’s not saying anything, it’s not insulting you – it’s just moving. We can easily and unintentionally create robots that will do that.”

This thesis project was designed by student Adi Manor, and supervised by Erel and Prof. Mario Mikulincer.

Robots can make people feel lonely and excluded

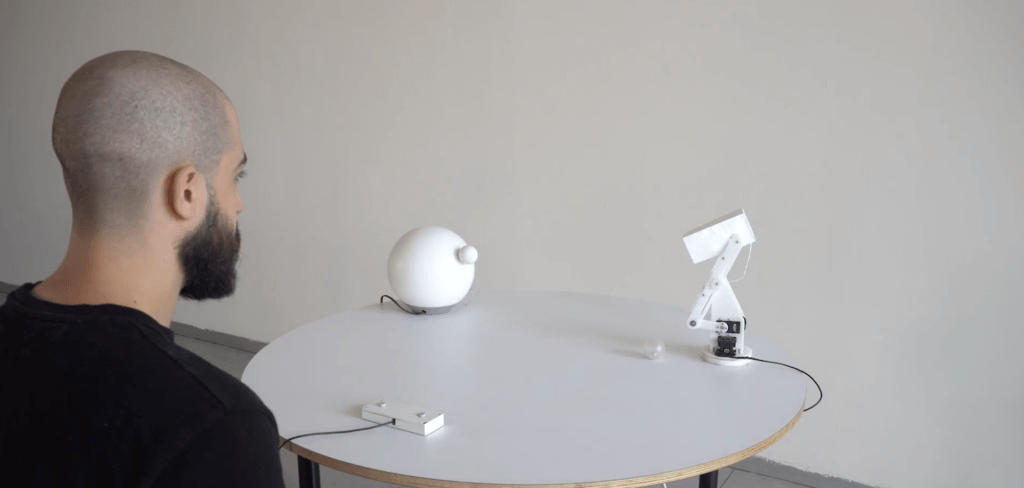

Robots that interact with one another, and exclude humans, could make us more lonely and more compliant.

Volunteers sat around a table with two robots for a simple game of rolling a ball. The volunteers could choose to roll the ball left or right by clicking a button. The robots had been programmed to “play fair” and roll the ball to the human participants a third of the time, in one group.

But robots deliberately ignored the humans in another group, and only rolled the ball to them in 10 percent of cases. The volunteers had to sit and watch the two robots pass the ball to each other for most of the session.

It’s a simple game – but it had a profound effect on the participants who barely got a turn.

“This created intense negative social emotions. People would say things like, ‘I could leave and nobody would notice.’ So you can design technology around us that will be super-smart and is supposed to be helpful, but will make people feel highly rejected,” says Erel.

The same participants then went into a room to be interviewed by a human (with no robots included), and were invited to bring a chair in. Those who barely got the ball chose to sit right next to the interviewer, while those that got the ball 33 percent of the time sat across the interviewer.

The results also indicate that they not only crave social interaction more, but are more compliant. Those who barely got the ball were more willing to fill out a questionnaire afterwards than those who didn’t get the ball as much.

So what can be done to prevent robots from making people feel insecure and increase their stereotypical biases?

Erel believes that it’s the responsibility of academia to map the extent of the problem, and that it’s unreasonable to expect the industry to do it.

“In academia we have the privilege to just understand how things work, and how they impact humans, both for the good but also for the bad. And then I think the industry must be super aware of what academia is doing, learn from it, and avoid it – that’s when it becomes the industry’s responsibility. If you already know that there is a problem, you cannot ignore it.”

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments