An ongoing Augmented Reality art exhibit initiated by the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens is drawing great interest from across the globe.

The exhibit, “Seeing the Invisible,” features 13 immersive virtual works by established and emerging artists including Ai Weiwei, Refik Anadol, El Anatsui, Mohammed Kazem, Sarah Meyohas, Pamela Rosenkranz, Timur Si-Qin, and Israelis Sigalit Landau and Ori Gersht.

The Augmented Reality artwork has been featured at 12 gardens in six countries since September, including in Israel.

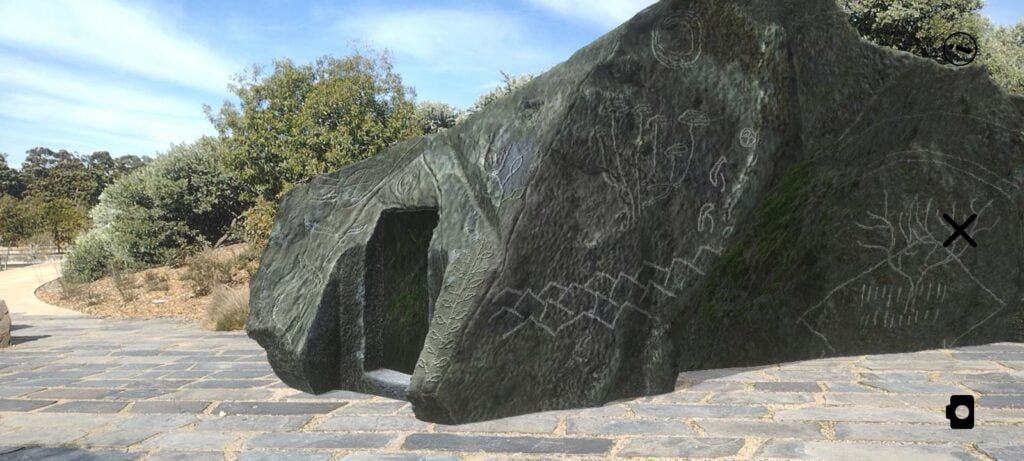

The large-scale installations are invisible to the naked eye. To view the art, visitors must use a dedicated Augmented Reality (AR) app, which superimposes images, text, and sounds on top of the open green spaces in the garden.

AR is an enhanced version of the real physical world which is achieved when a physical real-world environment is enhanced with computer-generated, digital visual elements, sound, or other sensory stimuli delivered through technology.

SEE ALSO: First-Ever Retrospective Of Renowned Japanese Artist Yayoi Kusama Opens In Israel

The idea for this exhibit came from the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens in partnership with Outset Contemporary Art Fund, with the support of the Jerusalem Foundation. The development of this augmented reality (AR) contemporary art exhibition has been an international collaboration all along. This is the first exhibition of its kind to be developed in collaboration with botanical gardens and art institutions from around the world.

“The Jerusalem Botanical Garden collaborates with a lot of different botanical gardens around the world. We share scientific information about our collections. When it comes to art and art exhibitions, we hadn’t had the opportunity to lead anything. It has been really exciting to lead this project,” Hannah Rendell, executive director of the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens, tells NoCamels.

The exhibit launched in Australia, Israel, South Africa, the UK, Canada, and the USA — and was meant to run for one year, from September 2021 through August 2022. But requests for this outdoor art show are growing and the exhibition is now being translated into new languages to meet demand.

“We have a lot of gardens contacting us to do it next year. We’d like to get [the exhibit guide] translated into Spanish. We already have it in Hebrew, Arabic, and English,” says Rendell. “We’re aiming for 30-50 gardens next year. It’s really, really exciting.”

12 variations of the same exhibit

“Seeing the Invisible” was born out of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which museums and galleries shut their doors and virtual tours of galleries were the only way to get a dose of art and culture. As the world began to learn to live with the virus, open-air art exhibits began popping up in museum courtyards, at city squares, and in gardens.

In Jerusalem, a 2020 outdoor art exhibit by the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens called “Returning to Nature” hosted 16 sculptures by Israeli artists peppered throughout the gardens. It was well-received and delighted many art and nature lovers who could finally go out to enjoy a day of culture. The executive board of the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens caught the art bug to develop a new exhibition.

“Gardens around the world have engaged with art projects along the years,” Hadas Maor, who curated the 2020 exhibit and co-curated the “Seeing the Invisible” exhibit with Tal Michael Haring, tells NoCamels.

The costs of importing art and the possibility of destroying the flora are behind-the-scenes aspects that led to thinking up a different kind of art showcase for the botanical gardens.

“Most botanical gardens use art as a way of engaging with new audiences and getting people to come to their garden. But it comes with a cost … the transportation of the sculptures or the work, it can destroy flora, it takes space within the garden, massive insurances, and the carbon footprint. So, straightaway, the digital aspect [of this exhibit] took all of these things off the table,” says Rendell.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

While art museums the world over added digital experiences to their collections that could be viewed from home during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, to see this exhibit, visitors must be present at one of the participating botanical gardens and use the dedicated “Seeing the Invisible” mobile app (developed for this project) on site. Each garden has a trail map to follow, and at each spot, a physical signpost marks the area to scan for the artwork to spring to life.

“This platform is beautiful because it really opens up a huge scope,” says Maor. “It’s immersive. You have to walk into the work in order to reveal it.”

It is one exhibit on display in different gardens. But even then, each trail route was curated for its specific surroundings.

“We curated the exhibition with a corpus of 13 works. The artworks are the same. Each garden is different, and we curated slightly differently for each garden. So, it’s like 12 different variations on the same exhibition,” says Maor.

Phygital – physicial and digital

“Seeing the Invisible” is as much about the artwork as it is about the greenery surrounding it. The exhibit tackles themes of nature, the environment, and sustainability, and explores the connections between art, technology, and nature.

“Visitors reveal the garden while revealing the works, it’s combined,” says Maor. “You have to go through the garden, you see the different vegetation, you move from a dry area to a wet area. For instance, Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s work of a 3D scanned cactus organ is positioned in all the gardens in an area that has similar type of vegetation. There’s a specific thought about the position of each work in each garden, that the visitor accumulates without even thinking about it.”

Maor reiterates that although a digital exhibit, “Seeing the Invisible” cannot be experienced online but rather requires people to physically visit the gardens. She terms this a “phygital” experience — combining the physical location and the digital manifestation.

“I don’t think it’s going to replace museums, and I don’t think AR or VR technologies are going to diminish a painting and sculpture and photography and video art. It’s another medium that has penetrated the art field,” says Maor, about the need to consider physical and digital realms in the art world.

Some of the 13 installations in this exhibit “existed before in a physical dimension and they were translated into AR, and some works were created, especially for the exhibition,” says Maor.

Included in the exhibition are Landau’s Salt Stalagmite #1 installation that explores the notion of a bridge as a means of connecting people, cultures, and languages, and activating peace;

Weiwei’s large-scale gilded cage, which addresses power structures, confinement, and restriction, as well as preservation and nurturing; and Daito Manabe’s endlessly dancing digital figure that morphs into new shapes against the laws of physics.

Bring earphones to hear and see Pamela Rosenkranz’s Anamazon (Limb) as it pulses and oozes or to watch and listen to Refik Anadol’s mesmerizing artificial intelligence work that pushes us to experience an alternate nature or to see and hear how Gersht’s sensuous and a bouquet of flowers explode in nature or to dive into Iceland’s glacial caves with Isaac Julien’s five-screen experience.

Hop on over to any one of 12 botanical gardens around the world now hosting the “Seeing the Invisible” augmented reality contemporary art exhibition, take a tablet or smartphone with you.

“It’s sort of a mind game,” says Maor. “It’s all on the screen but you do feel you’re in the art. That’s the phygital experience.”

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments