Israel is a nation made up of immigrants and Yom Ha’Aliyah – literally the Day of Ascending (those who take the decision to move to the Holy Land are considered spiritually elevated) celebrates the more than 3.3 million people who have packed up their lives and started again in the Jewish state since its establishment in 1948.

Indeed, according to a recent Jewish Agency for Israel press release, immigration to Israel in 2021 showed a more-than-30 percent year-on-year increase compared with 2020 – both of which were severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Yom Ha’Aliyah Act, which was established by the Knesset in 2016, is celebrated on the seventh day of the Jewish month of Cheshvan and coincides with the Torah portion of Lech Lecha, in which God commands Abraham to go to the Land of Israel. The aim of the holiday is to celebrate the development of Israel as a multicultural society and emphasize the importance of Aliyah to Israel.

NoCamels interviewed four olim (immigrants), each of whom are involved in the tech ecosystem, although in diverse fields – from language learning to eCommerce and from working for Facebook to mechanical diagnostic kits for a range of diseases.

Each of them arrived in the country more than 10 years ago – with three of them having been helped to do so by Nefesh B’Nefesh, in cooperation with the Aliyah and Integration Ministry, The Jewish Agency for Israel, Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael and JNF-USA – and has experienced both life and work in the Diaspora and in Israel, providing them with a balanced perspective on the trials and tribulations of living in the Holy Land, as well as the enormous benefits. Although the luster of being a new immigrant has somewhat worn off, it has been replaced by something deeper and each of the interviewees expressed a love and appreciation for the country.

“The greatest risk in life is not taking a risk at all”

Avi Moskowitz, originally arrived from Brooklyn in 1994 and like many people in those times, shuttled backward and forward between the United States and Israel. In 2015, he shifted his focus to being principally Israel-based, which coincided with his launch of BeerBazaar, a Jerusalem watering hole situated in the thriving Mahane Yehudah market that serves more than 100 craft beers, many of them locally brewed.

The business was constructed around a brewery and different branches, and Moskowitz began to build a website in 2018. With e-commerce platform expert Liran Erez advising, the website was launched just before COVID-19 and the attendant lockdowns hit. “We quickly realized that we wouldn’t have a problem with customers,” Moskowitz remarked, “but we did anticipate that we might have issues with order fulfilment.”

In 2020, Moskowitz and Erez, along with Shlomo Schwartz, who at one stage worked with Israeli public transport app Moovit, doubled down and decided to open another company – PDQ – which simplifies ecommerce logistics and enables merchants to meet the ever-increasing customer expectation for faster and lower-cost shipping.

The issue of shipping is an important one and the length of time and the ease with which a customer can receive their items, absolutely crucial in a company making a sale. “Approximately 25 percent of abandoned carts online – people who visit a website and put items in their carts but don’t finalize payment – is simply down to shipping issues,” Moskowitz explains. “Ours is a sticky product,” he adds, “we can provide up to 80 percent operational savings and the platform is built in such a way to give merchants several options such as offering a pick up from store, delivery from store or selecting a third party logistics company.”

Moskowitz’ parents survived the Holocaust and immigrated to the United States and were hesitant that any of their children should experience life as an immigrant in an unfamiliar country again. In fact, each of the interviewees acknowledged the impact of the cultural complex, but assessed that it was just another obstacle to be navigated and overcome. There is a truism about immigrants – particularly ones who move earlier in their lives – that one can feel a sense of dislocation. The country that one comes from moves on and changes, so that one doesn’t feel part as full a part of that nation anymore. And on the other side of the ledger, the place that one moves to has an education system, a culture and a language to name but three aspects with which the immigrant may be largely unfamiliar.

Embracing the struggle of learning a new language

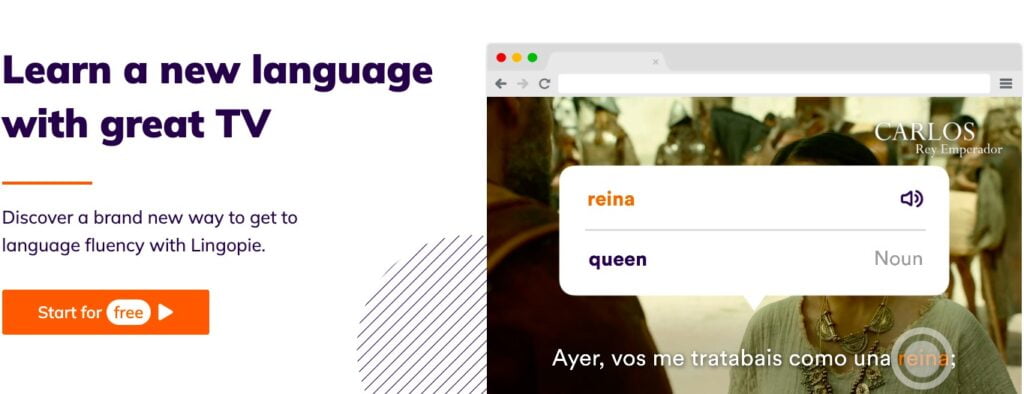

Speaking of languages, David Datny, who made aliyah in 2009 and arrived with little knowledge of Hebrew, is the CEO and Co-founder of Lingopie, a learning app that uses real TV shows and movies to help customers learn a new language.

“When I first entered the job market here, I worked at Seeking Alpha, because there were not that many jobs new immigrants with limited Hebrew could do – and many Israelis would not hire olim (immigrants),” he said.

“Gradually, there were some Internet startup companies – involved in medical tech or semi-conductors and some cyber – but it wasn’t Saas or B2B. It’s very different today and relatively easy to land a job. An immigrant could basically work for any company; Israelis see the value in olim and not just because we speak and understand English but also how Americans think. Companies value our expertise in marketing and we are largely treated the same as Israelis. There is not inherently more value added to being a native-born Israeli, except for a bigger and deeper network comprised of school and the army – we don’t really have that.”

Datny explained that there are no longer serious barriers to English-speaking immigrants being successful in the tech ecosystem. “Today, you can get a better job. Even an entry-level job has upward mobility; and the olim who were able to climb represent an inspirational story.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

Subscribe

His epiphany about starting to think about language app came out of the blue while riding in a taxi cab. While struggling to learn the language at one of Israel’s immersive and intensive daily language schools that new immigrants have access to in their basket of benefits, Datny wondered why so many Israelis seemed to be able to speak English fluently. His cab driver (and others) remarked that they learnt from watching English language TV and movies.

“I had never really thought about language as a separate product or realized that there was a problem that required a solution,” he emphasized. Working at an early fintech company, Datny would end up meeting his Lingopie co-founder and realized that they had learnt English and Hebrew in similar ways. In order to test the proof of concept, the pair “built something very simple.”

He related what he termed a “classic startup story.” The small team put the proof of concept on Reddit, using a “niche” language – Russian. “The feedback was instantaneous and intense and based on our experience we executed, built a team, raised money and went about making something more robust.”

Datny maintains that he would not have been able to build his product if he had not struggled through the immersion process of trying to learn a new language. “I will always be an American living in Israel but when you watch ‘Fauda’ or ‘Shtissel,’ you’re getting a peek into Israeli culture. It’s not my world and even though I live here, it’s still totally foreign to me but it does show the power of TV and movies.”

Living the Zionist dream

Jordana, who works as a user experience researcher at a large multinational tech company, arrived in Israel via London originally, and subsequently New York.

Making aliyah in 2011, she says that it was always a dream to do so, in particular wanting her children to be able to “inhale their Judaism, be surrounded by it and for it to be natural for them.”

Starting her career as a researcher, she explains that it was never a specific goal to get into the tech world. “Until now the user research field has been small but it has begun to grow. It was all a bit embryonic, but there are starting to be more opportunities.”

In fact, Jordana explains that there are “significant opportunities for olim” who bring wider experience simply by virtue of where they come from. Like the other interviewees, she feels pride and gratitude to be olim contributing to Israel’s tech success. “In a wider sense, it is also Israel’s success, too. I do feel that I’m living part of the Zionist dream. Israelis are doing really cool things… and I’m a part of that,” she exclaimed.

Jordana is also sanguine about the role of women in the tech ecosystem in Israel. “There is a bit of a culture clash; Israeli society as a whole is very male-dominated and the same could be said of the tech field. However, women in Israel are doing a lot to break this and plenty of them who have come before me have had it much tougher than I’ve experienced.”

Stephen Marx arrived in Israel from Dallas Texas in 2005, although he did not become an Israeli citizen until 2010. An academic with a PhD in cellular biology, Marx has the sort of mind that can identify patterns where others may not.

“One of the reasons I made aliyah is that I was told that it would be easier setting up a company in Israel, rather than establishing it in the United States and running it out of Israel. I was never involved in the tech world before and some of the best advice I got was from a business advisor. ‘You are going to make mistakes,’ he said, ‘the goal here is to ensure they are not so bad that they take you down,” he recalls.

Marx’s company – Marx BioTechnology – develops mechanical blood diagnostic kits for a range of diseases, including Graft versus hot disease (GvHD). The benefit of the company’s testing is that it can identify the disease in an earlier phase, before any physical symptoms appear.

“I feel blessed to have been born into this generation,” Moskowitz acknowledges. “There are so many magical and miraculous things that have brought us to where we are today. You have to find your place, and we have to sacrifice to have this country and land, and own the opportunity to be here,” he concludes.

Related posts

Editors’ & Readers’ Choice: 10 Favorite NoCamels Articles

Forward Facing: What Does The Future Hold For Israeli High-Tech?

Impact Innovation: Israeli Startups That Could Shape Our Future

Facebook comments