Just 15 years ago, the prognosis for someone diagnosed with myeloid leukemia (CML) was extremely bleak. But now, thanks to a decade-long study on an Israeli-designed drug, that’s no longer the case.

Sam Fields, a Jewish-American professional hockey player, was diagnosed with CML in 2003 at the age of 27. At the time, his doctors told him he only had two weeks to live. “They gave me a death sentence,” Fields said in an interview.

Amazingly, Fields, who is now 40-years-old, has been cancer free for almost 15 years. He attributes his being alive today to Gleevec, a cancer drug which was still in an experimental phase in 2003 when he first started taking it, but which has now come full circle.

SEE ALSO: Breastfeeding May Reduce Risk Of Childhood Leukemia, Study Shows

Mel Mann was a 37-year-old major in the U.S. Army with a wife and a five-year-old daughter when he was diagnosed CML and given three years to live. In August 1998, Mann was one of 20 patients that started the Phase I clinical trial for the drug STI571, now known as Gleevec. The drug was approved by the FDA in 2001 and Mel is still taking the drug today, making him one of the longest living Gleevec patients.

An 11-year study, 83.3% survival rate

Dr. Brian Druker, who led the original clinical development of Gleevec, co-authored the worldwide study which included 1,106 participants at 177 cancer centers in more than 16 countries. The study, published in the March 9th edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, shows that Gleevec keeps chronic CML at bay a full decade into treatment — with no signs of additional safety risks.

The story really begins back in 2001, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) granted priority review for imatinib mesylate, sold under the name Gleevec, as an oral therapy for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, or CML.

The nearly 11-year long follow-up study showed an estimated overall survival rate of 83.3 percent. According to the National Cancer Institute, prior to Gleevec’s 2001 FDA approval, fewer than 1 in 3 CML patients survived five years past diagnosis.

SEE ALSO: Researchers Find Why Leukemia Recurs After Successful Chemotherapy

“The long-term success of this treatment confirms the remarkable success we’ve seen since the very first Gleevec trials,” Dr. Druker, director of the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and JELD-WEN Chair of Leukemia Research in the OHSU School of Medicine, said in a statement. “This study reinforces the notion that we can create effective and non-toxic therapies.”

Gleevec: Shutting down cancer cells without harming healthy ones

The discovery of Gleevec ushered in the era of personalized cancer medicine, proving it was possible to shut down cells that enable cancer to grow without harming healthy ones.

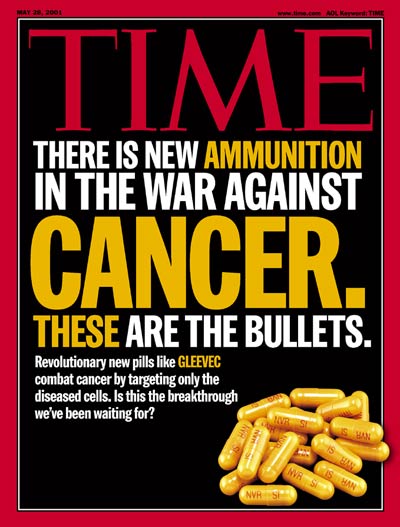

Gleevec was the first drug on the market to directly target the cancer-causing cells in CML, while leaving healthy cells alone. Fast-tracked through clinical trials and approved by the FDA in 2001 for treatment under certain circumstances, Gleevec held out the promise of turning a fatal disease into a manageable condition. Time magazine even put the drug on its cover and dubbed it a “bullet” against cancer.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter

SubscribeInspired by Israelis

Gleevec was in fact invented in the 1990’s by biochemist Nicholas Lyndon, although it’s success is most often attributed to Dr. Druker, who pioneered its use for the treatment of CML.

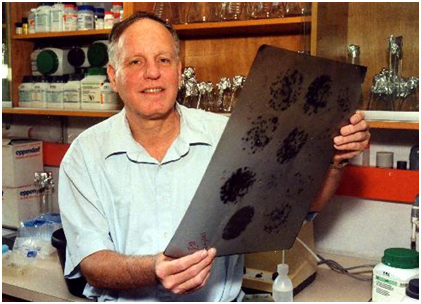

But Druker’s work was built on groundbreaking scientific research carried out in the 1980’s by an Israeli researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Professor Eli Canaani, working together with visiting American hematologist Robert Gale. At Canaani’s lab in Israel, he and Gale were the first to discover that when two key genes had a deviation in which they swapped pieces of genetic material, the result was a fused protein that triggered the cancer.

“This was the first demonstration that a cancer-specific DNA rearrangement joins two specific genes and causes a fusion of their encoded proteins to form a cancer protein,” Canaani said in a statement.

The abnormal fusion, known as the Philadelphia translocation or Philadelphia chromosome, results in a gene called BCR-ABL. Gleevec works by inhibiting the fusion of the BCR and ABL genes.

Until Canaani’s discovery, doctors knew about the binding of the two genes, but had not understood its significance.

“Along came Eli Canaani and Robert Gale, and they showed that a new gene that isn’t present in any normal cell is actually created. It then became apparent to everybody in the field that this new gene could be driving the formation of the cancer cells,” Druker explains.

“If Dr. Brian Druker is the father of Gleevec, then Professor Eli Canaani is the grandfather,” Eric Heffler, national executive director of the Israel Cancer Research Fund, a charity that supports cancer research in Israel and funded Canaani’s research said.

He shoots, Gleevec scores

Hockey player Fields was very straightforward when talking about the option of taking Gleevec.

“I had two choices,” Fields said in a recent interview. “I could quit or I could fight, and I wasn’t about to quit. If this is the only shot I have, why not try it and die than not try it and die?”

For Fields and Mann, and many others. it ended up saving their lives.

Photos and video: Israel Cancer Research Fund, Courtesy

Related posts

Israeli Medical Technologies That Could Change The World

Harnessing Our Own Bodies For Side Effect-Free Weight Loss

Missing Protein Could Unlock Treatment For Aggressive Lung Cancer

Facebook comments